How Road Salt And Environmental Racism Caused A Crisis In Flint

Header by Rory Midhani

Header by Rory Midhani

As you’ve no doubt read by now, a state of emergency has been declared in Flint, Michigan, for unsafe levels of lead in the city’s drinking water. The health hazard followed an April 2014 change in the city’s water supply. Under the direction of a state-appointed emergency manager (of which Flint had four between 2011-2015!), Flint switched from Detroit’s water system (which pumps water out of Lake Huron) to Flint’s own treatment plant (which draws water from the Flint River). Though the city has since switched back to their original source, the emergency continues to worsen, with recent reports linking an outbreak of Legionnaires disease with poor water quality. Members of the National Guard are now traveling door to door handing out bottled water, home filters and lead testing kits.

According to census data analyzed by the Detroit Free Press, somewhere in the neighborhood of 8,657 children under the age of six have been exposed to lead as a result of Flint’s water issues. Although lead exposure is bad news for people of every age, it’s particularly devastating for young children. The World Health Organization explains:

Lead affects children’s brain development resulting in reduced intelligence quotient (IQ), behavioral changes such as shortening of attention span and increased antisocial behavior, and reduced educational attainment. Lead exposure also causes anemia, hypertension, renal impairment, immunotoxicity and toxicity to the reproductive organs. The neurological and behavioral effects of lead are believed to be irreversible.

…Yeah. Terrible.

Reading all this, I couldn’t help but wonder: how in the world did all that lead get into Flint’s water in the first place? More importantly: why? Let’s explore.

A map previously used during protests against Flint’s water quality hangs in the home of area resident Tony Palladeno Jr., 53, on Monday, May 18, 2015 in Flint. Palladeno has been regularly active at protests as well as City Council meetings. Brittany Greeson via MLive.com.

From Roadways to the River

Michigan, like many states in the Northeast and Midwest United States, is a heavy user of rock salt during the winter months to de-ice roads. While salt water has been applied to prevent public roads from freezing since at least Victorian times, the practice was first applied to modern pavement in New Hampshire in 1938. Within three years, industrial spreaders were being used for dry surface salting and gritting with a total of 5,000 tons of salt being spread on highways nationwide. Today, it’s estimated that upwards of 22 million tons of salt are scattered on US roads annually.

The reason road salt works to de-ice roads is pretty simple. Sodium chloride — or NaCl, the ionic compound that makes up both table salt and pure road salt — is very soluble in water. When it dissolves, it breaks apart into two distinct ions (Na+ and Cl-). These particles disrupt water’s ability to form crystalline ice, lowering the freezing point in proportion to the number of ions floating around. This keeps going until the salt concentration hits about 25%, at which point the freezing temperature of the solution cannot go any lower. Different ionic compounds can be used (calcium chloride is a popular choice when it’s too cold out for sodium chloride to do its thing effectively!), but rock salt has proven cheap and readily available. While this is great for improving driving conditions, it’s unfortunately not so great for the environment.

Rock salt is loaded at a facility near Detroit, Michigan; the city has its own rock salt mine. PHOTOGRAPH BY PAUL SANCYA, AP. Via National Geographic.

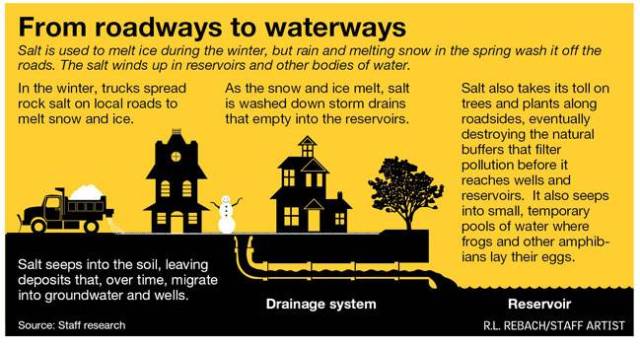

When salt is on the road, birds often mistake the crystals for seeds or grit, resulting in toxicosis and death. Deer are also attracted to roads to eat the salt crystals, leading to higher incidents of vehicular accidents and wildlife kills. As warmer temperatures arrive and snow begins to melt, salt splashes and sprays off to the side of the road, entering the soil. Through ion exchange, sodium (Na+) stays within the soil and releases other ions such as Calcium (Ca), Magnesium (Mg), and Potassium (K) into the groundwater, damaging foliage. Runoff washes down storm drains and into reservoirs, endangering sensitive aquatic communities and reducing species diversity.

Although road salt pollution is usually a bigger issue for the surrounding environment and (non-human) organisms that live in it, it can become a real problem for human beings when it comes up against our infrastructure. Chloride (Cl-) from dissolved salt accelerates corrosion, eating away at bridges, power line utilities and parking garage structures — or in the case of Flint, the plumbing that carries their drinking water.

Via NorthJersey.com.

The Corrosive Effects of Chloride

As salt-laden runoff enters a freshwater body, the higher density solution settles to the bottom, usually in areas where current velocities are low. It sits there impeding turnover and mixing, preventing the dissolved oxygen at the top from going down, and nutrients at the bottom from going up. Unless human activity disturbs it, the salt generally accumulates and persists. Only dilution reduces its concentration.

Unsurprisingly, we’ve seen lots of build up over the past several decades, with chloride concentrations in northern US states approximately doubling from 1990 to 2011. Michigan is known to be particularly salty, with high levels of chloride in streams near urban areas. When Flint switched their water supply from Lake Huron to the Flint River, they suddenly found themselves facing eight times the amount of chloride. Almost immediately, residents began to notice a change in the look, smell and taste of their tap water.

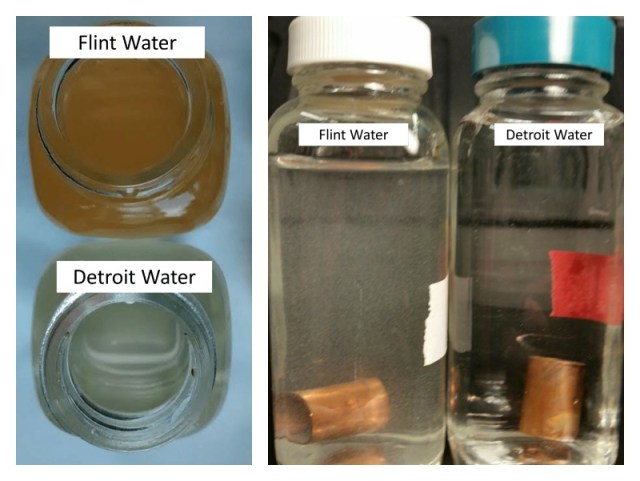

Flint Water Study lab samples. Left, iron pipe corrosion study: Pieces of iron were put in water samples from Flint and Detroit. A higher release of iron was evident in the Flint water. Right, copper pipe corrosion study: Even with the addition of rust inhibitor, Flint water visibly leached lead (the white suspended particles) from copper pipe + lead solder. Detroit water remained clear.

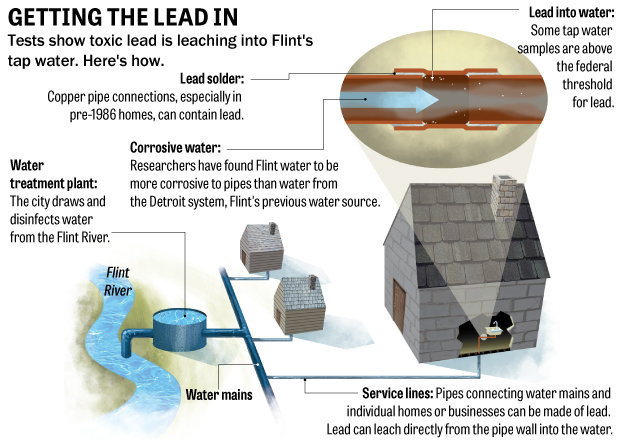

The most noticeable change was the color — now an “icky brown” that some residents believed to be sewage. In fact, the color came from iron in the pipes, which were now being rapidly eaten away by the corrosive water. Less noticeably, lead was also being released from a variety of sources: pure lead service pipes (many city-owned), pipes with lead solder (which was legal and the standard until 1986), galvanized iron pipes (which often contain lead), and brass plumbing devices containing lead (which were standard until January 2014). The subsequent amounts of lead measured in Flint’s drinking water were frighteningly high.

Via MLive.

A Health Hazard Dangerously Mishandled

Although Flint is not the only city to face this problem, its handling of the situation is the worst in United States history. Full stop. When Washington, D.C. faced a similar drinking water crisis in 2004, they were able to address the issue by treating their water with orthophosphate, a corrosion inhibitor. This and other corrosion inhibitors work by increasing the pH (aka. decreasing the acidity) of the water and forming a film to coat the inside of the pipes so that they corrode less quickly and leach less lead. Although the Detroit water was treated with corrosion inhibitor, inexplicably, Flint chose not to pursue this when they switched sources. Discontinuing the use of corrosion inhibitors allowed toxic scale build-up to flow freely into people’s homes. Though the city has since switched back to Detroit water, the EPA warns that health hazards remain.

As the situation now stands, so much damage has been done to the Flint water distribution system that it may not even be possible to meet Federal standards via chemical water treatment alone. Certainly the harm already inflicted on Flint residents cannot be undone at this point.

Ariana Hawk, 25, a pregnant mother of two, said her 2-year-old son has rashes on his face and body from exposure to the contaminated water. Via NBC News.

I think what disturbs me the most about this situation is the cavalier, belittling attitudes government officials have displayed throughout this entire process. Though they were aware of resident complaints as early as July 2015, it took until January 5, 2016 for a state of emergency to be declared. For months, government officials gave assurances to the public that their water was safe — meanwhile ignoring very compelling evidence from a variety of sources that showed otherwise. A couple highlights:

- In September 2015, when Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha — who is MPH program director for the pediatric residency at the Hurley Children’s Hospital at Hurley Medical Center, a professor at Michigan State University’s College of Human Medicine, and sits on the Michigan Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics — went public with findings of elevated blood-lead levels among Flint children, the state swiftly dismissed her research, with a spokesman appearing on national news to characterize her work as “unfortunate,” “irresponsible” and “near hysteria.” (She was, of course, entirely correct, and the state had data confirming it.)

- In October 2015, a leaked memo from a US Environmental Protection Agency official explained how Michigan’s process for lead testing in Flint’s water delivered artificially low results. “It is clear from several, now available documents, that certain MDEQ and EPA staff chose to put their reputations ahead of the safety and health of Flint citizens,” said Senate Minority Leader Jim Ananich. (That’s good that they’re taking at least some ownership. But why was this information only revealed when a document leaked?)

Though there’s certainly national media attention on Flint now, it’s hard to imagine the situation getting this out of hand in a whiter, wealthier community. Things ain’t how they should be.

Protestors march along Saginaw Street demanding clean water outside of Flint City Hall in Flint, Mich. on Wednesday Oct. 7, 2015. Via Christian Randolph, MLive.com.

An Opportunity for Justice

Shocking as this particular case may be, environmental disparities and uneven enforcement of environmental law is commonplace in the United States. Residents of Flint (57% Black; 41.5% living below the poverty level) know this firsthand. Beyond the city’s history of poorly handled water issues, Flint has faced environmental issues and apparent government indifference for decades, particularly following the collapse of the auto industry. In 1994, for example, environmental justice activists filed a complaint with the EPA to block construction of a biomass plant, arguing that low-income African Americans have already suffered enough from the concentration of pollution and poverty in the northeast quarter. The EPA noted the request on its list of civil rights complaints, but has yet to respond, even after repeated follow up requests from filers. Meanwhile, the biomass plant has been running for 20 years, burning wasted wood, pellets and old houses.

Writing about a case of environmental racism in Alabama, Ebony recently explained:

In accordance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the EPA’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR) is responsible for guarding against discriminatory practices or outcomes among EPA funding recipients. But strangely enough out of 298 complaints filed across 22 years, the OCR has never made a finding of discrimination. In fact, more than half of the complaints never lead to investigations at all and were instead rejected for various reasons.

Very suspect. Reportedly, there are changes in the works, but why has it taken this long? When the government agency specifically tasked with protecting these communities is allowed to behave this way for two uninterrupted decades, what does that say about our priorities?

Although access to clean drinking water is a widely agreed upon, globally recognized human right, the residents of Flint haven’t had a reliable public water supply in place for close to two years. While this manmade disaster was most likely the result of penny-pinching, face-saving and generally poor decision making rather than intentional racism, it certainly fits the larger pattern in this country where people of color disproportionately face social and ecological burdens. Centuries of discriminatory and oppressive policies have pushed Black people into cities with poor infrastructure and environmental hazards, with particularly disproportionate exposure to lead. What’s we’re seeing in Flint right now are the appalling effects of institutional racism unfolding. Right now. Real time.

How do we stop it? And for harm already inflicted, what kind of reparations, if any, can be made?

A bridge over the Flint River. Via Shutterstock.

Additional Resources

- Flint Water Study – Scientific explanations about what’s going on in Flint, compiled by researchers at Virginia Tech.

- How to help Flint, Michigan – The Rachel Maddow Show is keeping an updated list.

- What’s On Tap? Grading Drinking Water in U.S. Cities – The Natural Resources Defense Council’s comprehensive overview of tap water distribution in the United States.

- EPA: Your Drinking Water – Actionable information about how to improve your own water situation, including information on tap water filters and bottled water. There’s also a tool to look up federally required annual drinking water quality reports; however, you can often get better results just by plugging “[your city name] water quality report” into Google.

- Environmental Justice, Denied – A series by the Center for Public Integrity on environmental problems that disproportionately affect communities of color.

Notes From A Queer Engineer is a recurring column with an expected periodicity of 14 days. The subject matter may not be explicitly queer, but the industrial engineer writing it sure is. This is a peek at the notes she’s been doodling in the margins.