How One Woman Inventor Revolutionized Ice Cream

Header by Rory Midhani,

Header by Rory Midhani,

We’ve reached the tail end of summer and ice cream is taking up even more space in my brain than usual. The coquito cart across the street from my work sells double scoops of coconut ice cream for $2, which I have been taking advantage of daily at lunch. In the evening, a walk too far in any direction always seems to land me squarely in front of a Mister Softee truck, digging at the bottom of my purse for cash with which to buy a vanilla ice cream cone with rainbow sprinkles. I’ve recently discovered that the grocery store nearest my apartment carries adorable little pints of Ben & Jerry’s Pistachio Pistachio, which means that I’m now blissfully consuming it multiple nights a week — sometimes with dinner, sometimes as dinner. It’s sick, it’s glorious, and I wouldn’t do summer any other way.

Mister Softee via Shutterstock. Coco Helado via High Low Food Drink.

In the headlines this week, everyone was abuzz with news of melt-resistant ice cream and fridges with built-in ice cream makers. Although it seems there’s ice cream nearly everywhere you turn today, this fantastic frozen confection wasn’t always available to the masses. In fact, for most of the 19th century, ice cream was a rare treat enjoyed primarily by upper class people. This began to change 172 years ago today, when Nancy M. Johnson, an American woman from Philadelphia, received a patent for the first hand-crank ice cream freezer.

Grab some ice cream and let’s celebrate this woman’s mechanical genius!

This image represents my current feelings about ice cream. Via Shutterstock.

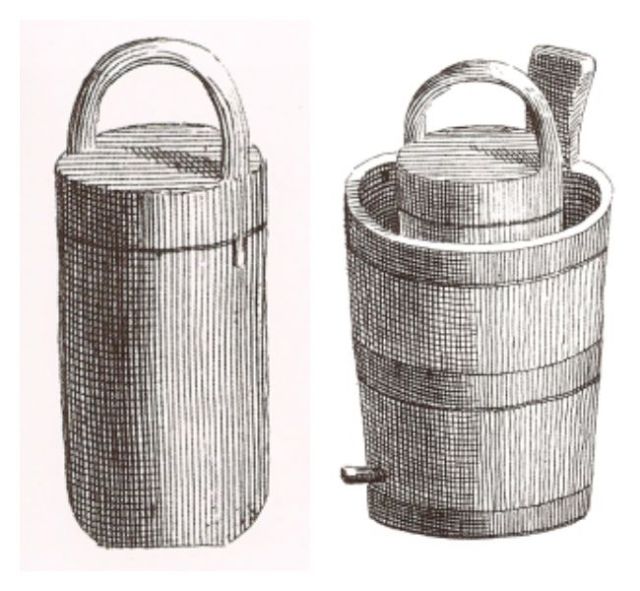

Prior to 1843, the standard way of making ice cream was known as the “pot-freezer” method. Users placed a metal pot inside of a “freezer” bin full of ice, added ice cream ingredients to the pot, and agitated the mixture by hand. Although this practice had been in place and working relatively well for almost two centuries, it was very labor intensive. Even when the French added a handle to the top of the pail and called it a sorbetière, it was difficult and extremely time consuming.

To operate this sorbetière, users placed the container in a tub of ice and salt and turned it round and round by hand. Then they would open the lid, stir, scrape the sides, close the lid, and spin the container again. Via Historic Cookery.

Similar to pre-existing methods, Johnson’s ice cream making method consisted of an outer bucket packed with ice and salt, and a metal container inside to hold milk, sugar and flavorings. The salt lowered the freezing point of the ice, allowing the inner container to reliably reach a cold enough temperature that a thin layer of milk would freeze to the inside of the inner container. Ice cream was made by scraping a frozen layer from the edge, allowing a new layer to freeze, and repeating the process until the whole mixture was frozen.

Yet while older machines relied on operators to scrape down the sides of the inner container by hand, Johnson’s invention ingeniously placed a crank on the outside, connected by meshed gears to a rotating paddle (known as a “dasher”) on the inside. The dasher would move ingredients from the edge of the freezer to the center and back again, “thus constantly allowing fresh portions of the cream or other substance to be frozen to come in contact with the refrigerating surface.” When the mechanism stopped turning, the ice cream was frozen and ready to eat.

Here’s an example of how a machine based on Johnson’s design operates:

In 1843, this was an absolute game changer. No longer did a cook need to spend hours manually stirring and scraping by hand. All that was required now was to load the machine and turn the crank! Johnson’s invention made ice cream creation more accessible on the basis of ingredients, too, with an outer tub diameter only three to four inches larger than the freezer. Combined with the lid, this meant that less ice and salt was required to keep the freezer cold — a significant feature during an era when cooks most commonly purchased natural ice delivered by truck. Johnson’s ice cream even had a smoother consistency, thanks to the consistently cold environment and regular stirring made possible by her machine.

Johnson patented her invention under Patent No. 3254 and sold the rights to wholesaler William G. Young, who began marketing it in 1848 as the Johnson Patent Ice-Cream freezer. Although several other patents were given around the same time (including an invention by salesman Thomas Masters in England in the same year, and Eber C. Seaman’s large scale commercial invention five years later), Johnson’s is the first on record. Her basic design and many associated iterations are still in use today, including many home ice cream makers currently on the market.

Top: Donvier Manual Ice Cream Maker. Bottom: MaxiMatic EIM-502 Elite Gourmet, Donvier Pint Size Ice Cream Maker, White Mountain F64306-X 6-Quart Hand-Crank Ice Cream Freezer.

Little else is known about Nancy M. Johnson except that she died in Quaker City at an advanced age. Historical accounts differ on what city Johnson resided in, how much she was paid by Young for her patent rights, and even when the patent was issued (although it says it clearly on the patent document itself). While I’m a little saddened by this (there are so many more details available about most male inventors from the time!), I also find it sort of comforting that a person can be remembered exclusively for an excellent piece of work that they did. I’ll be thinking of Johnson’s invention today as I eat ice cream with my lunch. And afternoon snack. And dinner.

Notes From A Queer Engineer is a recurring column with an expected periodicity of 14 days. The subject matter may not be explicitly queer, but the industrial engineer writing it sure is. This is a peek at the notes she’s been doodling in the margins.