How I Learned to Talk (In Bed): Why This Queer Woman Cares About Consent

I came into the consent movement almost by accident. It was a hot and sticky Washington, D.C. summer and I was 18, straight, and a feminist. I stumbled onto a conference about preventing violence against women and I went to it on a whim. And I met Nancy Schwartzman. One email later, I was her intern.

VINTAGE CARMEN, CIRCA 2009 IN THE LINE OFFICE

It was the summer of 2009, and I would wear sundresses to Nancy’s office around three times a week. I took the NJ PATH train after a NJTransit train to get there, and I was listening to a lot of Of Montreal at the time. We were working on THE LINE Campaign, an interactive campaign about consent. Nancy is an extremely brilliant sex-positive consent activist, and I was inspired and still am inspired by her work and her attitude. When we were working together, I was disarmed and awed by her idea of consent: that it was a universal concept for everyone, that women should have as much sex as they damn well feel like just like boys, that the question of “can we do this” could be asked by anyone of any gender or sexual orientation or background and in any sexual situation, and that consent was to be ultimately respected and never violated. That sex should, intrinsically, be about consent.

I was sold.

THE LINE Campaign is based around a short documentary by the same name, which was produced, directed, and filmed by Nancy. It asks its audience one seemingly simple question: where is your line?

A SUBMITTED CAMPAIGN STICKER FOR THE LINE

When it comes to sex, we all have boundaries. Seriously. I don’t care if your boundary is “no more than four girls at once.” It’s a boundary, and it’s worth talking about. When you’re having sex with someone, you are culpable for two things: your boundaries, and their boundaries. You need to make sure you’re comfortable, and it is just as important that they are comfortable. You need to ask for sex, and they need to ask for sex. That’s how it works. A healthy sexual relationship, even if it’s a casual one-time sexual experience, is based in that communication: being able to articulate desire, and being able to act on someone else’s.

“Enthusiastic consent” is about asking and listening. And it’s a powerful feminist concept that could change our entire world. The consent-positive movement is about more than “no.” It’s about “yes.” It’s about waiting for someone to verbally, enthusiastically, consent to having sex with you before you start having sex with them. No still means no. Violating that no is still wrong. But in addition, only “yes” can mean yes: not silence, or a short skirt, or the fact that we met you at Jello Wrestling and fucked you last week. Consent is about being able to say “I want this / I don’t want this” and being respected. It’s about expecting to hear some variation of one of those phrases when you begin to engage in sex. It’s about a completely safe, comfortable, and pleasurable kind of sex. Consent makes it possible for every single person in the world to have completely different boundaries and desires and still feel fulfilled and respected in bed. I liked that.

And so I took it home.

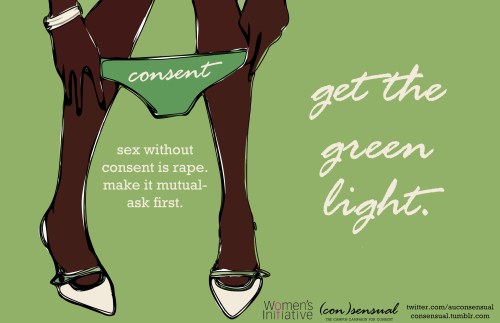

a (con)sensual poster

In August of 2009, I implemented an educational campaign on my campus called (con)sensual, which was based in getting people interested in the concept of consent and then prompting them to attend events where they could learn more and talk more about it in order to become more comfortable with it. I wanted consent to belong to everyone – not just to the feminist community. And as I returned to school, I took on the role of writing and, later, editing THE LINE’s campaign blog. I was talking to people on a personal and global level about consent, respect, and navigating the college hook-up culture. I had already committed, in my mind, to taking on this work for the rest of my life.

Then I came out of the closet.

When I came out, I felt disconnected from my work. By this point, I had been organizing and educating around consent for 2 years. I had been selected to speak at the SPARK Summit about that work mere days before I drank a 4Loko and took my best friends into my bedroom to tell them I was gay before going out to a party. It was then that my organizing came to a sudden stop. My writing ended abruptly. I didn’t want to talk about consent anymore – not because I didn’t still believe in the movement and its purpose, but because I felt like I was starting all over again. All of the work I had done on consent was based around my personal experience as a straight woman. How could I go back and touch that topic again now, as someone else?

Consent should belong to everyone. Because consent is not about preventing violence or fixing rape culture. (That’s a bonus.) Consent is about having sex on our own terms, no matter what they are in that instant. But globally, the dominant conversation about sex and consent is about men and women having sex and utilizing consent. Many times, the patriarchal gender norms of our world also dictate how sex and consent work in the bedroom. And all of these conversations may make you, as a queer woman, feel pretty excluded by the consent movement. And maybe you even think, like I did, that consent just isn’t for or about you. But it is.

And I know because when I started having sex with women, I started to ask.

Talking to someone is a great way to convince yourself that you actually understand how they’re feeling, and is extra helpful when you aren’t even sure how you’re feeling. In fact, it’s the only way to gather information on how your partner is feeling that’s accurate, unless you are a bona fide psychic. And so I started to talk. Let’s be honest: our first sexual experiences with women were awkward. Or scary – in the good way. Or clumsy. Or confusing. Or overwhelming. Right? It happens.

Talking made me feel more comfortable with what was going on, and allowed me to explore my sexuality more wholly. I started to ask, and suddenly it wasn’t that overwhelming. In fact, I really liked it. I really, really, really liked it. And I liked what consent added to the experience, too:

I started small, with basic consent questions.

“Is this okay?”

But sometimes life is a lot more complex than whether or not you’re having sex. Sometimes I had questions about feelings.

“Are you okay?”

Sometimes I had questions about the process.

“What do you want?”

Sometimes I was hoping to relieve my anxiety that I wasn’t doing too well.

“Did you like that?”

And I learned how to say yes, I did, or no, could you do this instead. But also: yes. I did.

“I really like this.”

Applying what I knew about consent helped me unpack my first sexual experiences. I felt present. Like I was finally living in my own body. I was finally enjoying sex, after a lifetime of waiting for that feeling. And I was finally learning to be comfortable with that.

You may have never been told before that you can initiate, desire, and seek out sex as a woman. But you can. And you may have never really envisioned yourself being in the driver’s seat of your sexual experiences. But you are. Consent fills us with a new power to talk about desire without shame, to talk about pleasure without fear, to seek out sex without danger. If we lived in a world where consent was the newest thing and everyone was doing it, sex would be an equitable and empowering and pleasurable experience – every time, for every person – and everyone would be able to ask. And everyone would also be able to answer. Because that’s how consent works.

My work around consent is, primarily, about getting people excited about consent and getting people to apply it in their own experiences. That’s easier said then done – because sex is not a simple concept or a homogenous experience. So I work on breaking down how it is people ask, and emphasizing why it’s important.

As a queer woman, I feel now that my experience with consent is varied and broad. I’m familiar with asking, and with being asked, with saying no, with saying yes, with being rejected, with being accepted with open arms. Consent is a process. It’s a thing you acquire and it becomes a lifestyle of making sure you respect boundaries, even if they haven’t been previously verbalized to you. If you want to become a part of the consent-positive movement, it’s as easy as 1-2-ask. You become a part of the movement in doing, not in learning or interning or talking about the doing. You become a part of the consent-positive movement when you seek out the yes.

So go get it.