The show is over, the lights come up. The actors take their bows; small Alison jumps on big Alison’s back, and they all run out of the room. Throughout the audience, people are sniffling, rifling through their bags for any tissues they may have missed. I almost ask the woman next to me if she needs a hug. Because while the last 100 minutes gave us plenty of opportunity for laughter, shock and nostalgia, the overwhelming feeling in the room that night is wistful sadness.

Fun Home, the musical adaptation of the Alison Bechdel graphic memoir that so many of us love, opened on Broadway on April 19. Since then, it’s received a dozen Tony nominations, among other awards and accolades, and many of its performances have sold out. The one I saw did; two empty seats in front of me appeared to be the only no-shows in the entire Circle in the Square theater. The crowd was diverse in age and appearance, but everyone seemed taken in by the story of an adult Alison (Beth Malone) remembering a chaotic youth marked by her father’s strange behavior and eventual suicide.

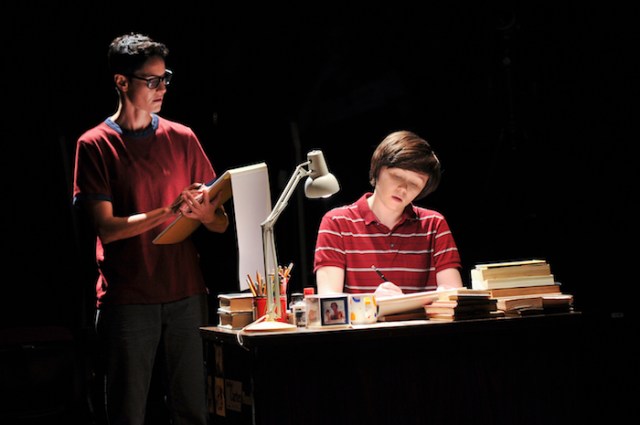

Photo by Joan Marcus

The three versions we get of Bechdel — “Small Alison,” “Middle Alison,” and just plain “Alison,” according to the playbill — are each in a discovery phase of their shared life. Both young Alisons are stumbling toward maturity, trying to express themselves to a father who has a wholly different vision of her. Adult Alison knows he won’t understand, but continuously kicks herself for not explaining better, demanding answers. Early on, she announces what those who have read the memoir already know: This story will end with her father, Bruce (Michael Cerveris), committing suicide. She has limited time to speak with him before then, to learn what she can about how his warped, intangible trajectory affected her own development.

Because Alison is a lesbian, as she discovers in stages charmingly familiar to queer viewers. She is also a cartoonist, drawn to a medium her father refuses to take seriously. She doesn’t know what she wants to be like as an adult, but it’s not reflected in any of the adults around her. Her mother, Helen (Judy Kuhn), is robbed of her own dreams and resigned to living with a man who has no affection for her. Bruce, a big, shouting, singing force, is nonetheless opaque, living with lies and loneliness. Middle Alison (Emily Skeggs) starts to get an idea of the right track for her when she falls in love with Joan (Roberta Colindrez‘s truly dreamy, self-described collegiate dyke) but even then struggles to really say the words: I am a lesbian. And when she finally does, her parents act like they don’t hear her. It’s the same struggle that millions of young queer people endure every day, one that I endured.

That’s why I felt stung during one of small Alison’s pivotal scenes. Eating in a diner with her father, who is busy reading, Alison notices a delivery woman no one else seems to pay much attention to. She is strong, a butch with short hair, boots and, Alison sings triumphantly, a large ring of KEYS! Alison, who has struggled to dress comfortably while her father pressures her to fit in with other girls, revels in the realization that a grown woman could dress like this and be okay. She has received the first piece of her role model puzzle. Sitting in the audience, hearing those around me laugh at an admittedly silly musical number, made me want to get up and defend the girl on stage. Her story is the one that’s still developing! I thought. This is a huge deal for her! Take this seriously!

Like many of my reactions to this play, this one came from a deeply personal experience as a queer woman. Which is great, and powerful, and exactly what good theater should inspire. But weirdly enough, it was a moment in which I felt othered — in a theater with visibly queer people! during a play about a lesbian and her gay dad! — acutely aware of all those in the audience who were there out of curiosity about something they had never experienced. It made me empathize even more with adult Alison, who throughout the play cringes and blushes at her younger selves’ more awkward moments.

Photo by Joan Marcus

Media representations of childhood are inherently revisionist — reproduced by adults, they search for complex meaning in youthful experiences that, while multifaceted and complicated, were lived by a less-developed mind. To a child, cause-and-effect reasoning is a blunt tool, and varied daily experiences are often viewed sequentially rather than in relation to one another: I didn’t eat my lunch; then I was starving all afternoon; then I had three servings at dinner; then I threw up on the carpet; then Mom got mad at me. An adult would see each situation as leading to the next (if I had eaten lunch, I wouldn’t have gotten sick; if I hadn’t overeaten at dinner, my parent wouldn’t be upset) but a child doesn’t necessarily connect the dots. And an adult looking back on a situation from their childhood may connect dots that shade experiences in a way their younger self never felt.

Fun Home gets that. Throughout the story, adult Alison wanders the set, observing small details and wondering aloud if she’s remembered correctly. At times, she rushes to sketch details before they disappear; in other moments, square lights appear around multiple scenes simultaneously, as if she’s viewing the comic strip in her head faster than she can transcribe it. Staged in the round, the play has just enough set detail to keep the eye bouncing while characters bound in and out through a multipurpose door. Scenes flow organically from one to the next, and bare-bones representations of Bechdel’s father’s same-sex dalliances inspire a truly impressive amount of discomfort. Small Alison never knew about her dad’s affairs, and middle Alison can only piece together the components her mother reveals. But neither she nor the audience needs a full play-by-play to feel how wrong the encounters are.

Bruce is the loudest character in the play, and it would be easy to think of him as its main character. He’s the only one whose story gets a beginning, middle and end. But that would be a shortsighted view of what Fun Home is, and why it’s so important. The play, like the graphic memoir, is not just Bechdel’s recounting of her father’s painful, semi-closeted life. It’s an investigation, a desperate search to pin down how who Bruce was made Alison into who she is.

Photo by Jenny Anderson

It’s also a hilarious, emotionally sharp retrospective on growing up, from the delightful disco-themed commercial small Alison and her brothers record for the funeral home, to middle Alison’s declaration that she’s changing her major to Joan. The story interjects these joyous scenes with less comfortable ones of Bruce’s dalliances or family arguments, because that’s really what it’s like when you’re young. Good things happen, then bad ones, then funny ones, then awful ones.

Malone told the New York Times the story maintains that strict, investigatory sense as a reflection of Bechdel’s personal ethos: “Even her look is all about telling the truth — no ornamentation, nothing pretty. She hates lies — lies and embellishments are what got her dad killed.”

Without lies or embellishments, all Fun Home has is one woman’s messy set of memories. But those recollections are brilliantly recounted by actors who really seem like a family struggling to understand one another. Three representations of Bechdel feel both distinct and familiar, and the music is strong without overpowering the story. In the end, the play sticks with you for the same reasons the memoir did when you first read it: It reminds you how hard it is to understand who we are.

Fun Home is playing now at Circle in the Square theater in New York. Tickets are available at Telecharge.