The True Story Behind “Hidden Figures”

Header by Rory Midhani

Hello jellybeans! Have you all seen Hidden Figures yet? I hope so, because it is fantastic. Truly the best movie I’ve ever seen about women in STEM. It’s important, it’s inspiring, and it’s beautiful and triumphant. In case you missed it, here’s my favorite trailer for the movie:

I went with my girlfriend on opening night and we were blown away — and hungry for more details on how much of it was actually true. Luckily, there’s plenty of data available on that front, because Hidden Figures is based on a recently released non-fiction book by Margot Lee Shetterly, Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race. I found the book to be a little scattered at first (understandable, considering its aim to cover the careers of several dozen women across multiple decades), but it really pulls together if you stick it out past the first few chapters. It’s worth it. The stories are incredible.

So! Let’s take a look together and see which parts of the film were fact, and which parts were beautiful, exquisite, powerful fiction.

FACT OR FICTION: John Glenn said “get the girl to check the numbers,” specifically requesting that Katherine Goble check the math on the trajectories before he boarded the Mercury capsule Friendship 7.

Fact. “Get the girl to check the numbers” is a direct quote from John Glenn, which Katherine overheard from her desk in building 1244 when the phone call to the engineer came in. Unlike the movie, Glenn didn’t expound on the request by adding Katherine’s name — whether because he didn’t know it, didn’t remember it, or didn’t need to — but it was obvious to everyone who he meant.

Writes Margot Lee Shetterly,

Spaceship-flying computers might be the future, but it didn’t mean John Glenn had to trust them. He did, however, trust the brainy fellas who controlled the computers. And the brainy fellas who controlled the computers trusted their computer, Katherine Johnson. It was as simple as eight-grade math; by the transitive property of equality, therefore, John Glenn trusted Katherine Johnson. The message got through to John Mayer or Ted Skopinski, who relayed it to Al Hamer or Alton Mayo, who delivered it to the person it was intended for.

“Get the girl to check the numbers,” said the astronaut. If she says the numbers are good, he told them, I’m ready to go.

Katherine Goble Johnson.

FACT OR FICTION: Al Harrison took a sledgehammer to the “colored girls” restroom sign, desegregating Langley’s campus.

Fiction. Al Harrison was not a real person, but a fictionalized composite of three NASA directors at Langley during the time. (The writer couldn’t get the rights to the guy he initially wanted.) There is no record of any of them ever personally taking down restroom signs; however, Miriam Mann from West Computing did take down the cafeteria sign.

Writes Shetterly,

It was Miriam Mann who finally decided it was too much to take. ‘There’s my sign for today,’ she would say upon entering the cafeteria, spying the placard designating their table in the back of the room. Not even five feet tall, her feet just grazing the floor when she sat down, Miriam Mann had a personality as outsized as she was tiny. The West Computers watched their colleague remove the sign and banish it to the recesses of her purse, her small act of defiance inspiring both anxiety and a sense of empowerment. The ritual played itself out with absurd regularity. The sign, placed by an unseen hand, made the unspoken rules of the cafeteria explicit. When Miriam snatched the sign, it took its leave for a few days, perhaps a week, maybe longer, before it was replaced with an identical twin, the letters of the new sign just as blankly menacing as its predecessor’s.

At some point during the war, the COLORED COMPUTERS sign disappeared into Miriam Mann’s purse and never came back. The separate office remained, as did the segregated bathrooms, but in the Battle of the West Area Cafeteria, the unseen hand had been forced to concede victory to its petite but relentless adversary.

Miriam Mann. Via NASA.

FACT OR FICTION: Katherine, Mary Jackson and Dorothy Vaughn were an inseparable trio, playing bridge together, carpooling to work together, and even sitting together at church.

Fiction. Though the women shared camaraderie and did work in West Computing together (Dorothy beginning in 1943, Mary in 1951, and Katherine in 1953), Katherine’s daily commute etc. was actually made with Eunice Smith.

Per Shetterly,

Eunice Smith lived three blocks down, and Katherine delighted in learning that her soror, neighbor, and fellow worshipper was also a nine-year West Computing veteran. In the early days of June 1953, when Eunice Smith drove over to Katherine’s house to pick her up for work, the two women started a routine that would persist for the next three decades. … Eunice Smith was Katherine’s steadfast companion and confidante. The two of them spent more time together than many married couples, commuting back and forth to work each day, serving together as officers of the Newport News chapter of their sorority, AKA, taking time off from work to root for their teams in the yearly Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA) basketball tournament for black colleges. They never missed Sunday service at Carver Memorial Presbyterian Church, and one night a week when they left Langley they headed over to Carver for choir practice.

Janelle Monáe, Taraji P. Henson and Octavia Spencer play Mary Jackson, Katherine Johnson and Dorothy Vaughn, respectively. Via 20th Century Fox.

FACT OR FICTION: Katherine used Euler’s method to determine the rocket’s trajectory for the Mercury-Atlas 6 mission.

Fact. The Hidden Figures script was vetted by NASA historians who ensured all of the math was accurate. Katherine used Euler’s method along with many other equations, which Shetterly describes,

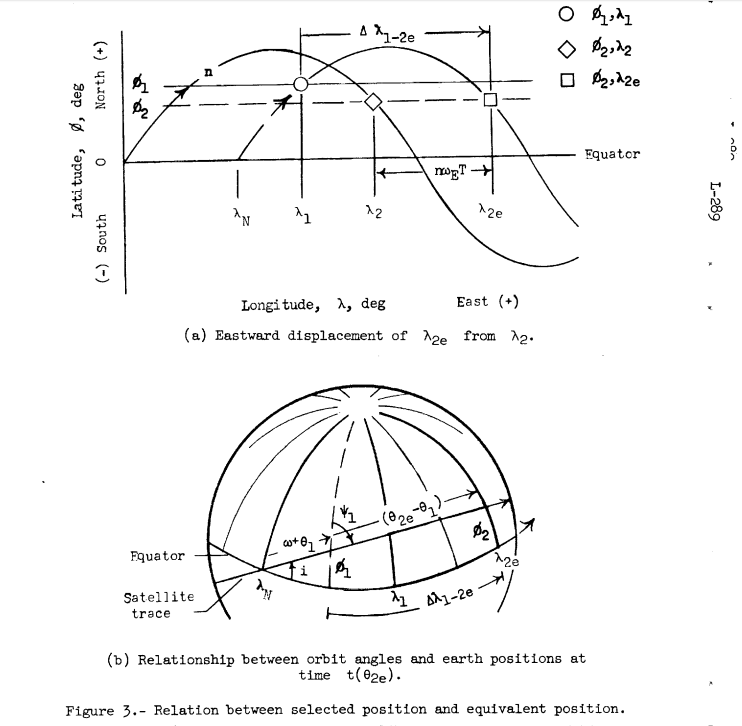

Sitting in the emptier office, she plunged into the analysis, although the pesky laws of physics turned an afternoon of rote celestial tennis practice into a forces free-for-all. Earth’s gravity exerted its force on the satellite and had to be accounted for in the trajectory’s system of equations. Earth’s oblateness — the fact that it was not perfectly spherical but slightly squat, like a mandarin orange — needed to be specified, as did the speed of the planet’s rotation. Even if the capsule were to shoot off into the air directly overhead and come back down in the same straight line, it would land in a different spot, because Earth had moved.

‘In the recovery of an artificial earth satellite it is necessary to bring the satellite over a preselected point above the earth from which the reentry is to be initiated,’ she wrote. Equation 3 described the satellite’s velocity. Equation 19 fixed the longitude position of the satellite at time T. Equation A3 accounted for errors in longitude. Equation A8 adjusted for Earth’s west-to-east rotation and oblation. She conferred with Ted Skopinski, consulted her textbooks, and did her own plotting. Over the months of 1959, the thirty-four-page end product took shape: twenty-two principal equations, nine error equations, two launch case studies, three reference texts (Including Forest Ray Moulton’s 1914 book), two tables with sample calculations, and three pages of charts.

Katherine’s full technical report (“Determination of Azimuth Angle at Burnout for Placing a Satellite Over a Selected Earth Position”) is available on NASA’s website, if you want to check out the math.

FACT OR FICTION: Katherine had to run half a mile across campus to go to the bathroom.

Fiction, though just barely. This activity did happen, but the scene in the movie was based on an experience Mary Jackson had. Katherine actually ignored the rules and used the women’s bathroom in her building.

Shetterly:

From the very beginning, Katherine felt completely at home at Langley. Nothing about the culture of the laboratory or her new office rattled her — not even the persistent racial segregation. At the beginning, in fact, she didn’t even realize the bathrooms were segregated. Not every building had a Colored bathroom, a fact that Mary Jackson had discovered so painfully during her rotation on the East Side. Though bathrooms for the black employees were clearly marked, most of the bathrooms — the ones implicitly designated for white employees — were unmarked. As far as Katherine was concerned, there was no reason why she shouldn’t use those as well. it would be a couple of years before she was confronted with the whole rigmarole of separate bathrooms. By then, she simply refused to change her habits — refused to so much as enter the Colored bathrooms. And that was that. No one ever said another word to her about it.

What a badass.

Notes From A Queer Engineer is a recurring column with an expected periodicity of 14 days. The subject matter may not be explicitly queer, but the industrial engineer writing it sure is. This is a peek at the notes she’s been doodling in the margins.