Clinical Trials on Trial: Medical Studies Still Exclude Women and People of Color to Dangerous Degree

If you consider yourself a feminist — or even if you don’t like the label but do like equality — the Health Equity and Accountability Act is a thing that you should care about.

Not familiar? Here’s the rundown:

- As you’re no doubt aware, per the patriarchy, the “default” population our society caters to is white men.

- When this pattern is repeated in medical research, we wind up with clinical trials that primarily focus on white, cisgender male bodies and fail to consider the physiological differences in other populations.

- Without adequate medical research on different types of bodies, women and racialized people unnecessarily face worse health outcomes when the results of this medical research roll out full scale.

These problems are well documented, and women’s health advocates have been pushing to improve this situation for several decades. An important victory was won in 1993 with the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act, a law mandating the inclusion of women and racial/ethnic minorities in clinical trials funded by NIH. The Food and Drug Administration also issued its “Guidelines for the Study and Evaluation of Gender Differences in the Clinical Evaluation of Drugs” that year, informing the pharmaceutical industry on how to evaluate data on women included in drug-development trials. In 1998, the FDA required that anyone enrolled in clinical studies be identified by gender, age and race, and that safety and effectiveness data be evaluated to identify differences based on these categories. Yet despite some progress, women and racialized people are still vastly underrepresented in clinical study data.

How many grams of patriarchy per pill, do you suppose? Via Shutterstock.

Last year, Ambien became the first and only prescription drug on the market with different recommended dosages for men and women. Although the sleeping medication had been approved and in use for over two decades, a series of high profile incidents led investigators to discover that the active ingredient, zolpidem, metabolizes differently in male and female bodies. By this time, thousands of women had received inappropriately high dosages — almost double what most female-assigned bodies need! — putting them at higher risk for adverse reactions such as “sleep driving.” In spite of this, the FDA still does not require sex- or race-specific analysis in the drug approval process, even when making dosage recommendations. They merely offer guidelines.

Alarmingly, the Ambien dosage debacle is just one example among many in which marginalized populations were exposed to significantly greater risk. Even for diseases which disproportionately affect women (such as lung cancer, heart disease, Alzheimer’s and depression), the only available medical treatments have largely been tested on men. For example, even though lung cancer is the top cause of cancer deaths among women and women now account for almost half of new cases and deaths, only 32% of lung cancer trial patients are women. And even though African Americans smoke less, they develop lung cancer at higher rates than white people — yet still represent less than 2% of lung cancer trial participants.

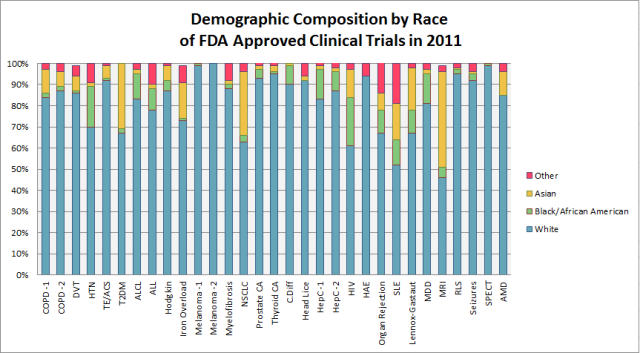

In an FDA report released August 2013, analysis of demographic subgroups showed that clinical trial participants were overwhelmingly white. Data via FDA.

As is often the case in STEM, the exclusion of women and POC from studies may relate, in part, to the demographics of investigators. Yet disparities between different stages of clinical trials and a closer look at the history of such studies reveals a much more complicated picture.

Modern scientific methods for clinical trials — including the use of placebos, blinding and comparison of effects between groups of individuals — were developed using new statistical methods during the 1930s and ’40s. Corresponding ethical guidelines, however, were not formally established for another few decades. During this period, numerous experiments were carried out without the knowledge or consent of participants. While this is far from an ideal situation for anyone, the results were particularly devastating for racialized populations, whose lives and bodies were often viewed as expendable pieces of public property.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study, for example, has become an infamous example of racist and unethical medical experimentation. Beginning in 1932, the United States Public Health Service began providing free “health care” to 600 African American men from rural Alabama, 399 of whom had syphilis. The men were never told that they were infected, nor were they ever treated, even after penicillin was established as a standard, effective treatment for the fatal disease in the mid ’40s. During the course of the study, researchers regularly lied to participants about what they were doing, and even orchestrated placebo treatments so as to continue unimpeded observation as the disease progressed. This continued until 1972, when a leak to the press turned the project into a public scandal.

What are the options for treatment that aren’t based in centuries-old oppressive systems? Via Shutterstock.

Outcry prompted new federal regulations, such as the creation of institutional review boards to govern the ethical conduct of research on human subjects. Interestingly, ethical principles outlined included justice, specifically in fairly distributing the benefits and burdens of medical research. (Clearly, it’s still a work in progress.)

One unintended consequence: broad interpretation of these guidelines meant that female-assigned people of childbearing age were excluded outright from clinical trials. This included people using contraception, as well as those who stated that they were not having sex with male-assigned people. For researchers, the “vulnerable population” in need of protecting was not women, but fetuses and potential fetuses. (That women’s health would suffer on the whole seemed not to be an issue.)

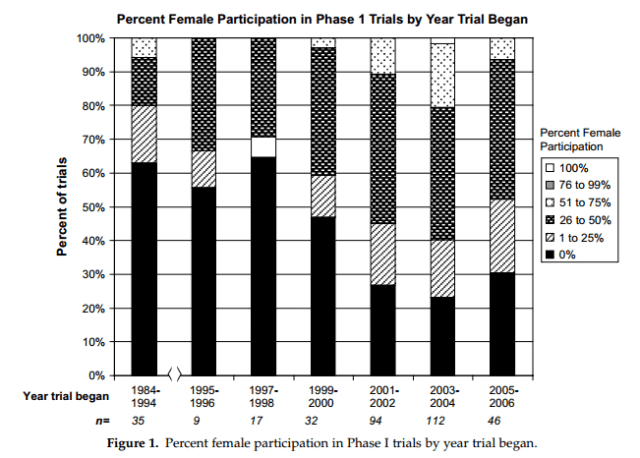

Today this legacy continues, with women vastly underrepresented in Phase I clinical trials. It is during this phase that dose-ranging activities take place, with researchers determining the optimal amounts that will provide the most benefit without unacceptable toxicity.

Meanwhile, underrepresentation of people of color is most prominent during later stages. Although the most prevalent explanation for this is widespread distrust among POC communities, studies have shown that this is less of a factor today than in the past. While it is true that some POC may (reasonably!) feel wary based on knowledge of past medical atrocities, accepting this as an immutable fact places blame on the wrong target. Clinics can overcome such barriers by focusing on building strong patient-clinician bonds and providing transparency.

In fact, there is already a high willingness among POC patients to participate in clinical research when asked — many are simply never made aware that studies are going on. For one thing, POC are less likely have access to health insurance, which is a prerequisite for gaining access to many medical facilities and some Phase III clinical trials (the stage at which patients undergo long term testing in blind, controlled studies). Due to economic oppression, POC are more likely to be seen by a variety of physicians who are unfamiliar with them (such as emergency room doctors), and who are therefore unlikely to enroll them in clinical trials. Even when POC have consistent primary care physicians, biases about racial groups may leave physicians less likely to suggest POC for clinical trials out of belief that they will not comply with difficult therapeutic regimens over long periods of time. (This in spite of the fact that “perfect” adherence is significantly more important in Phase I and II trials.)

Yet even when clinical trials include appropriate numbers of women and racialized people, a recent report by the FDA revealed that shortfalls remain in meaningful subgroup analysis. In other words: although data about women and POC may have been collected, the results were not separated out. Without subgroup analysis, medical professionals are not able to understand the full extent of effects or efficacy of products on different population groups. The best they can do in these situations is to either assume that the results are equally representative for everyone, or make an educated guess otherwise.

I’m so proud of my #HEAA2014 bill, which will promote #HealthEquity for all Americans! pic.twitter.com/9FcXmtSmIh

— Rep. Lucille Roybal-Allard (@RepRoybalAllard) July 30, 2014

So what’s being done about this?

As required by section 907 of the 2012 Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act, the FDA is currently assembling an Action Plan to provide recommendations on how to improve women and minority representation, subgroup analysis, and the availability to accurate information to doctors and consumers. The report will be released within the next month. However, given the limited resources the FDA has for enforcement, legislative action is critical to drive action.

On July 30, Representative Lucille Roybal-Allard introduced a bill called The Health Equity and Accountability Act, which provides a strategic plan to eliminate health disparities across racial, ethnic, ability, language, and gender groups. It would make federal resources available to target inequitable health care access, create federal guidelines for data collection and reporting, increase culturally and linguistically appropriate health care availability to communities of color, and even increase access to comprehensive sex education.

Although it takes a long time for the results of clinical trials to be realized, the NIH Revitalization Act passed over two decades ago, and our health care system is still far from equitable. When population groups are excluded from clinical studies, they are exposed to harm that could easily be avoided through more inclusive practices. Lack of information makes it impossible for women and people of color today to make fully informed decisions about their health, and denies them the right to advocate for what happens to their bodies. In 2014, this should no longer be acceptable.

The HEAA is supported by multiple POC advocacy groups, including the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, the Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus, and the Congressional Black Caucus. For opportunities to get involved, check out #HEAA2014 on Twitter.