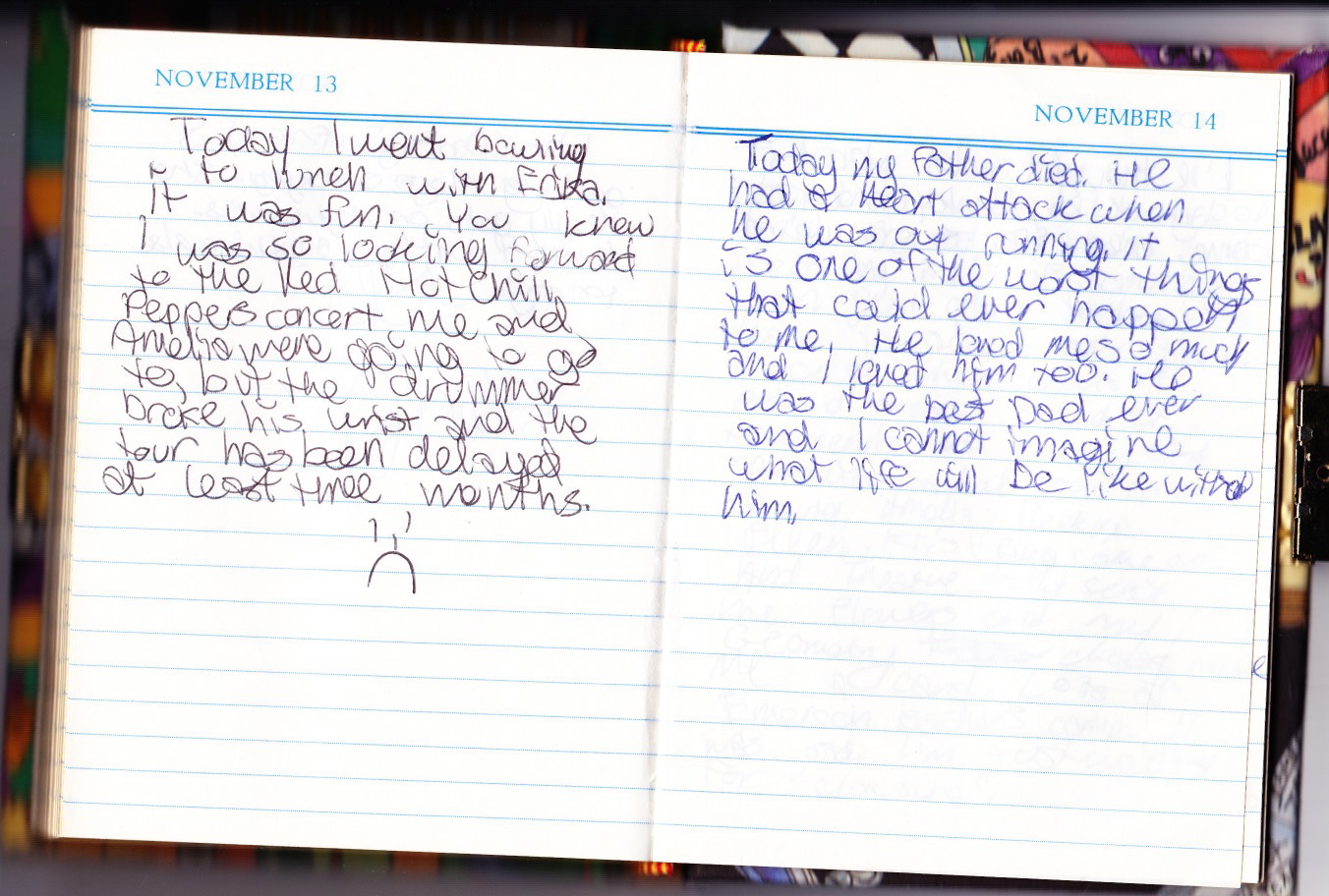

My father died when I was 14. My father died when I was 14. My father died when I was 14. Heart attack. While he was running. Training for a marathon. Yes, it was unexpected. Yes, just out of the blue. Yeah, just about the worst thing that could’ve ever happened, just really the absolute worst, nothing worse will ever happen to me! (I will laugh at this part, a little. To make sure you know it’s okay, that I can think about this thing and laugh at the same time.)

*

He didn’t feel any pain. He died instantly.

That was how my mother told me that my father was dead.

I was 14. It was Tuesday. After school, I’d gone to McDonald’s with my theater friends and eaten two plain cheeseburgers with french fries and a Coke. When we returned to school for rehersal, our director Phil told me that Michelle was coming to pick me up now ’cause my Dad was in the hospital and therefore couldn’t pick me up after rehearsal, as initially planned. My parents were divorced and Tuesdays were Dad night. Michelle was my Mom’s best friend and they’d met because in elementary school I’d been best friends with Michelle’s oldest daughter, Mandy, who had always been cooler than me and remained so.

He was having chest pains, Michelle explained. That was the whole story, that was all we knew. He’d never been in the hospital before, as far as I could remember. I assumed everything would be fine because this was about two hours before I learned that at any given moment, anything at all could happen, even something so terrible it seems impossible. Like you’re going somewhere and suddenly you are crushed by a falling rock. That’s how life is, it turns out.

Still, I considered the possibilities as we drove back to Michelle’s in her SUV. Surely it’s nothing serious, he’s fine, he’s healthy. I decided, for reasons that escape me now, that the absolute worst case scenario was my Dad going suddenly blind. I imagined him in the hospital, reaching for my hand to know I was there. I imagined holding his hand.

I think Mandy and I tried to talk a little bit when I was sent up to her bedroom to wait for my Mom, but everything was strained: I was an artsy dork going through an especially awkward phase, struggling to fit in at the giant public high school where I’d just begun 9th grade. She was, as she’d always been, popular and beautiful and athletic and wearing J Crew. She played field hockey at her private school and had a boyfriend. She was always kind to me, even now, long past our friendship’s expiration date, but I felt nervous around her, unpretty. I’d never kissed a boy, even, and my hair never got shiny like Mandy’s hair and I wasn’t good at dancing or outfits. I sat on the floor and did my geometry homework and wondered if Mandy painted her own toenails and then my Dad died.

*

My father died on November 14th, 1995, when I was 14. Every day since the day he died I am one day farther away from him than I was before. This is the truest thing about me. It is the most important and worst thing to ever happen to me. It is me. My father died when I was 14. I will tell people this forever. It is the truest thing about me. I was 14 when he died. My father. I was 14.

I am what I have lost.

I want to talk to you about how it feels to spend your whole life grieving, to feel nobody you know will ever truly know you ’cause they never knew him. How it feels to recycle 14 years of material like the greatest hits album a band puts out just before breaking up. Listening to it one more time, and then another time, until it starts to feel like the only music you’ve ever heard.

I haven’t written specifically about my father all that much since high school. But I write about him, indirectly, all the time. I’ve never given him an essay but I mention him in every essay I’ve ever written, don’t I? This is how I keep him alive. This is how I keep everybody who has left me alive: I write about them.

I was only 14. A heart attack from the deep blue beyond.

He’d been alive for 42 years and me, for just 14.

Things people said a lot, when it happened: He was so young. He was in such good shape. If it could happen to Vic, it could happen to anybody.

*

Michelle called me downstairs. My mother and 11-year-old brother, Lewis, were already in the high-ceilinged living room, sitting on the couch where I’d seen Grease for the first time.

If it’s any consolation, she said, you should know that he didn’t feel any pain. He died instantly.

I slipped my hand behind my ribcage, removed my heart, and smashed it into the carpet.

I know he’s been dead and I know what it means to be dead and I know how time works but I won’t stop looking for him or talking to him. I never saw the body, you know. My Mom had been in the hospital but I was doing my geometry homework.

In “Grudges,” a poem by Stephen Dunn, which I read for the first time in the tenth year since my father died, he writes:

Before you know it something’s over.

Suddenly someone’s missing at the table.

In The Year of Magical Thinking, a memoir by Joan Didion, which I read for the first time in the tenth year since my father died, she writes:

Life changes fast

Life changes in the instant.

You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.

I found him in those places, in those books. I found him in every boy and girl I’ve ever wanted — the ones that play guitar like he did, that read like he did, that edited me and wrote with me like he did, that traveled like he did, that loved the water like he did, that know how the Midwest feels under your feet like he did, that climbed mountains like he did, that make everything a joke how he did.

I found and I find him when I do the things he liked to do, like singing in the morning in my underwear even though I can’t sing. Like canoeing, hiking, making silly faces during serious conversations, watching college basketball, sailing, spending too much money on gifts, laughing with his mother and sisters, obsessively studying American history, obsessively planning travel itineraries, organizing complicated thematic social events, camping, expressing inflexibly ultra-liberal political opinions, making everybody participate in speculative business ideas over dinner, taking long drives.

The only good thing in my life right now is my Dad, I’d written in my diary, four days before he died.

I’ve never felt so connected to someone as I did to him. I think everybody’s got that person, it’s a spot defined by its limited capacity. Maybe it’s your wife, your mom, your brother, your sister, your best friend. When I sense even one faint chord of him in my connection with a new person, I dig my talons right in.

*

My dad was born in 1952 in Wilmington, Ohio and grew up on a farm with his parents and two sisters. He was nerdy and effortlessly landed at the top of his class and once built a machine to pitch baseballs at him ’cause his sisters didn’t want to. He started undergrad at Miami of Ohio, but transferred to Ohio State “in protest” of Miami’s position on Vietnam. He did his Master’s Degree and his PhD at The University of Illinois-Champaign, and one day in Champaign my mother was standing in a friend’s doorway when she saw a skinny drunk guy in the background who gave her a big Charlie Chaplin wave. They would marry, a Jewish girl from the city and a Quaker boy from the country, and have a daughter, and move to Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he had a job teaching at the business school. He was very good at his job, but we can talk about that later. He was sort of a hometown hero, just for leaving and being so successful and then taking his parents on vacation. Everything he did got written up in local paper back home.

Before you know it something’s over.

Suddenly someone’s missing at the table.

I remember the drive home from Michelle’s, wailing, pressing my feet into the mini-van floor like we’d all turn to sand and spill out if I didn’t put down roots. My Mom had just moved into a new house, one my father had only been in twice, which would help later when I tried to forget life had ever been better — I mean different — than this. I’d never walk into my Dad’s recently-built condo again.

I’d been upset when Mom moved out of the house we’d grown up in but now I was relieved because I only had one memory of him in the new house and in the old house I would’ve had billions. So here I was, a new person in a new life in a new house that we walked into, still hot and sad with tears.

I called my two best friends. Are you joking? They both asked. It was, you have to realize, the kind of thing I would’ve been joking about. (Is the kind of thing I still joke about.) My friends came over, dropped off by crying, dumbstruck parents suddenly panicking about their own mortality. He was so young. If it could happen to Vic, it could happen to anybody. My mom made tough phone calls. I can’t remember who had to tell his parents, it must have been my aunt. They loved him more than just about anything, you see.

There’s a part in my favorite television show Six Feet Under when Brenda says:

You know what I find interesting? If you lose a spouse, you’re called a widow, or a widower. If you’re a child and you lose your parents, then you’re an orphan. But what’s the word to describe a parent who loses a child? I guess that’s just too fucking awful to even have a name.

I think about that a lot. He wasn’t supposed to die first.

My grandfather had valium, I think. My Mom made me hot milk with Kahlua. My friends slept on my floor in sleeping bags.

Before you know it something’s over

Life changes in the instant

He died instantly

He didn’t feel any pain

We saved all the pain for you

Then, a Quaker funeral in Ohio, with his family, friends from back home, and far-away friends who flew in for it. We were all too sad to look at each other, or maybe I was too mad, mad at my cousins ’cause their Dads weren’t dead and mine was. At visitation everybody talked to me and Lewis like we were tiny animals in glass cages so eventually we hid in the stairwell. Why wasn’t I crying, I was asked, it’s okay to cry. How could I cry when I was so angry!

See, I’d requested a closed casket but there was his body in a box with its lid ajar for everybody to see, a line out the door of people wanting to see this dead body. I’d been overruled by the rest of the family. So I sat in the back row during the funeral. I wasn’t crying ’cause I’d already learned one thing: anger is the only emotion louder than sadness.

But also, this: they needed to see the body, and I needed to let them.

I guess that’s just too fucking awful to even have a name.

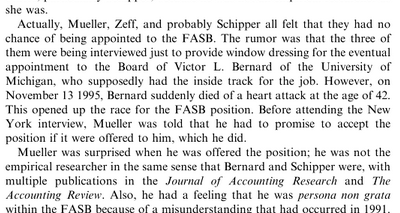

The Regents of the University of Michigan acknowledge with profound sadness the death on November 14, 1995, of Victor L. Bernard, the Price Waterhouse Professor of Accounting and director of the Paton Accounting Center.

Professor Bernard was a model faculty member who was among the most highly regarded researchers in his field as well as an outstanding teacher. His combination of academic excellence, approachability, and an unusual ability to communicate his knowledge effectively placed him in high demand. He was extremely generous in sharing his considerable knowledge and insights and never disappointed the many students, faculty, colleagues, and others from around the world who so frequently called upon him. In one of many acknowledgments of his extraordinary ability and character, Professor Bernard was the first recipient, in 1994, of the business school’s “Leadership in Teaching Award,” which recognized his contributions to students and to the development of junior faculty members.

Professor Bernard’s research was sometimes controversial and always highly respected. His work had significant impact in academia and business and provided his students with leading-edge knowledge. Professor Bernard was considered an expert on the savings and loan industry; he co-authored a book on the subject in 1989 and testified before Congress about the industry several times. A controversial series of publications he researched and wrote with a colleague documented a systematic inefficiency in the stock market; his work continues to generate interest and study on Wall Street and in academia. At the time of his death, Professor Bernard was excited about his work in the area of fundamental analysis, a method for company valuation on which he was breaking new ground. The recently published textbook he co-authored, Business Analysis and Valuation, provided state-of-the-art information on this subject.

Professor Bernard won the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants/American Accounting Association “Notable Contribution to the Accounting Literature Award” twice, a rare achievement. Another reflection of the esteem in which he was held was his selection as research director and executive committee member of the American Accounting Association. He earned his Ph.D. degree from the University of Illinois in 1982 and joined the Michigan faculty the same year. In just six years, he was promoted to tenured full professor.

Despite enviable achievement in his work, Professor Bernard’s life was filled with other pursuits that were profoundly important to him. He valued his work as a scout leader for his son Lewis, 11, and he was proud to serve as a softball coach for neighborhood girls when his daughter Marie, now 14, was younger. And he considered scaling Mount Kilimanjaro to be one of his greatest accomplishments.

Victor Bernard left behind a powerful legacy and set high standards for the School of Business Administration and the University. As we mourn the loss of this great scholar, teacher, advisor, and friend, our condolences go to his companion, Dara Faris; his former wife Maureen; his two children; his sisters, Brenda Custis and Connie Bishop; and his parents, Glenn Lewis and Erma S. Bernard.

(via)

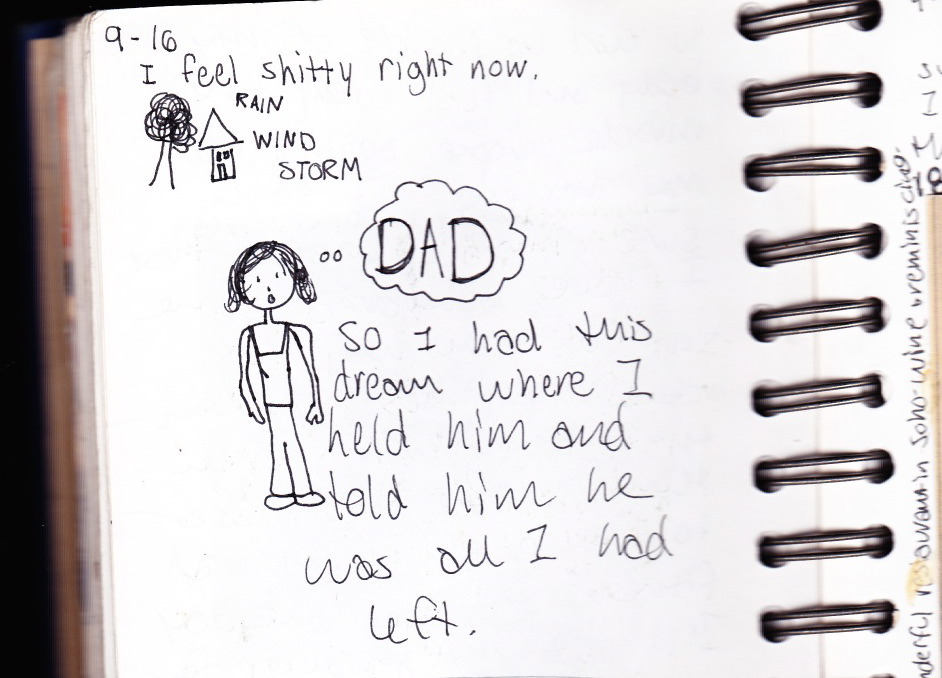

I find him in my dreams. It’s always the same dream: my father comes back to life but somebody else is dying or dead.

It’s a cold trade-off, but I’m never sad.

*

I always thought it would be me, my mother said. Her own mother had died when she was 14 and so she’d been waiting for that fate ever since my birthday.

My mother’s father had left the country before her mother had died, so as a teenager my Mom and her sister lived in an apartment in Chicago with their grandparents. Then they died, too, and then my mom found her father again — he’d moved to Australia, of all places — and within a few years of their reunion, he died of tongue cancer. I was nine. The divorce had been rough on my Mom, too, and just as she was finally healing from that, her now-ex-husband/best friend went and died on her. Although we’d been engaging in twice-daily screaming matches from holy hell for a few years at that point, we called a silent truce for a year or so after Dad died.

She must have been terrified to suddenly become the single mother of two grieving children, but the fact that she made it through, somehow, helped me believe that I could, too.

You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.

I remember the sliver of a view I had of the meeting room from the stairwell at the funeral, seeing my grandmother wailing at the casket, my grandfather helpless to hold her.

We’ve just been moving… slowly, my grandmother told Lewis and I after my Dad’s girlfriend dropped us off for Christmas five weeks after the funeral. My grandfather had just quit his job as a truck driver because the grief was just so enormous, the drives just so long. We sat in silence in a living room that once contained so much light in a house in the country where everything was so quiet you could hear your own heart break at night, and we did.

*

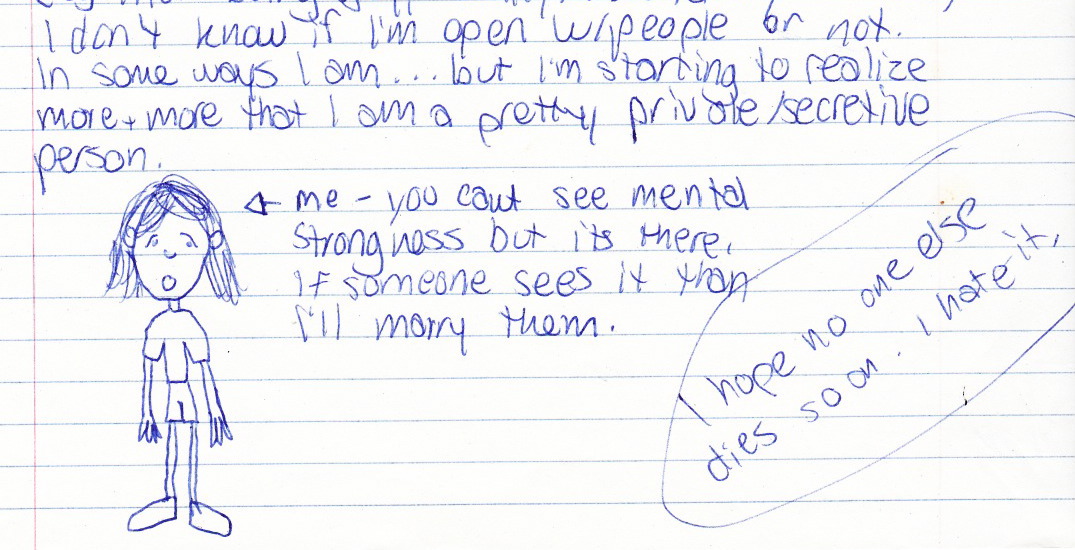

I decided early on that I would be the one who stayed strong, who wouldn’t let this be the death of me, too. I’m just going to block it out, I proudly informed anybody interested in listening. I wedged the grief into a tiny bit of space I made in my brain for things I didn’t want to think about anymore. In retrospect I realize it was unwise to move that huge thing into such a small space so early. I didn’t leave room for terrible things that hadn’t happened yet, for other things that I might’ve considered impossible that turned out to be possible after all. So you could say I chose to be strong, but it also made me more fragile. Instead of crying about my Dad, I cried about everything else.

Rosie O’Donnell, who lost her mother at the age of 10, has said this: “Losing a mother is always going to be like losing a limb, but to have that happen in your formative years is life-altering. It breaks and melts your heart, but then you form some kind of steel core as a result.”

That would be me. The steel core.

I’m a depressive, too, and maybe that’s why I was able to go on just the same. Being sad and depressed about everything all the time, in and of itself, wasn’t a new sensation.

On November 15th I wrote in my diary that I needed “closure.” I returned to school on Monday, November 20th. I could take more time, they said. I don’t want to be that far behind in class, I said. It would just be more work later, and who knows how I’ll feel later. I feel okay now, I need to do this now. That’s sort of how I’ve lived my life: when I feel okay, I work, because I can’t ever rely on how I might feel tomorrow.

Everybody told me it’d “hit me” later but I couldn’t think about later. I needed to get through the day.

How do you go on? I’m asked by people who have also lost a parent.

You go on. You just go on because there is no other option besides going on.

*

Grief in the beginning is specific. It is awkward questions and sad answers, it is rooms you once stood in together, only now it’s just you. Movies you wanted to see together, for example. You gradually remember all the things that won’t look like you’d thought they would: he’d never see Lewis’s Bar Mitzvah, he wouldn’t walk me down the aisle at my wedding. The first Christmas without him. Every Michigan basketball game without him. Every annual event reminds you of that same event one year ago, when he was still there.

There was a ski trip to Boyne already booked, for example. Mom didn’t ski. Who would wrap these two sad children in thick winter coats and noisy ski pants and take them to the mountain? My Mom’s friend Jolene was given the task. But we didn’t want to go skiing for its own sake. We wanted to hang out with our father, and if he wanted to do that on a mountain in a snowsuit with expensive pieces of wood strapped to our boots, then okay that would be fine. Now nothing felt right. It was cold, after all, and we were small and hungry and our hearts were just these icy bundles heaving behind our ribs.

I quit theater. I made some new friends, put glitter on my eyelids, listened to Frente! and The Lemonheads, watched bright-colored movies like Clueless and Empire Records over and over and over. I made music videos on my handycam and played a lot of Sim City. My aunt from Australia — my mother’s father’s daughter, who’d been ten when he died — stayed for a month. That was nice.

We’d been given so much food for sitting shiva that it filled up an entire freezer in the basement. I’d defrost enormous cookies and lie on my floor staring at the ceiling fan, chomping at the bit.

He got a lot of phone calls, even though he hadn’t lived under our number since the divorce. Is Victor Bernard here? They would ask. Or if they asked for my Mom and she wasn’t there, they’d say, well, Is Mr. Bernard available?

My Mom told me to tell solicitors that “nobody by that name lives here.” After the divorce, she’d told us to say the same thing to anybody who asked for Mrs. Bernard.

Instead, I told them, “No, he’s dead,” and then I’d hang up so I didn’t have to listen to them say I’m sorry.

*

There was a “grief group” at school. I was, apparently, one of ten or so kids who’d lost a parent in the last two years, and so the counseling department decided we needed a group of our own and I went because I got to miss Spanish. There were two faculty advisers who wanted us to know they were there for us, all of us, whenever we needed them. Luckily for me, I didn’t need anybody.

I rarely spoke. Mostly I looked at the other kids and evaluated who in the room was most entitled to their sorrow. Emily and Farrah, blonde sisters so popular they were practically famous, had lost their mother to cancer. It was a slow death, it took years, and therefore my small bitter brain decided to categorize their pain as less than mine because they’d had a warning and a chance to say goodbye.

But Rebecca, who was nerdy and awkward with shocks of frizzy, curly hair so unruly and glasses so large that it was hard to tell what her face looked like — she had it worst, I decided, she had it so bad that I wondered if she even belonged in this group. We’d never understand her pain. Rebecca’s father had jumped off a bridge.

*

I was sent to a therapist, and then another. This continued for some time. It was all a game to me and the game was: will I get out of this room without crying? I usually won.

I turned 15. My mom came out. Later that year, I left for boarding school, and that was the beginning of a life containing very few memories of my life before November 14th, 1995.

After the first year, which is the hardest, things stay pretty much the same forever. Grief becomes you.

*

Every day at 11:14 AM and 11:14 PM. Every damn day.

Every November 14th. Every damn year.

At first, we acknowledged the date — I’d get cards from friends, I’d call my grandmother and my mother and all that, even though I didn’t understand yet the point of this anniversary. He’s just as dead today as he was yesterday, I’d say.

I didn’t know yet that when you get older you need to make time to pay tribute, you need an excuse to do the thing Raymond Carver writes about in Another Mystery: today I reeled this clutter up from the depths… I reached through to the other side.

Every Father’s Day. Every damn year.

People just want to know where your dad lives and if he works at the university; they don’t know how loaded those questions are for some people. It’s easier for me just to avoid small talk with strangers altogether. It’s become chronic, honestly.

What do your parents do?

Where do your parents live?

Are your parents tall, too?

Does it run in the family?

Are both your parents Jewish?

Are your parents married?

No, they’re divorced.

Do they both live in Ann Arbor?

Um, my mom does.

What about your Dad? Are your parents remarried?

My dad lives underground in a cemetery in Ohio and my mom is gay now, so like, legally, she can’t remarry, actually?

Do they wish they’d never asked? I think they do.

My father died when I was 14. I will tell people this again and again and again for the rest of my life.

*

In 1999, found him in A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, when Dave Eggers, who has lost both of his parents in the same year, takes off with his younger brother and writes:

Look at us, goddamit. The two of us, slingshotted from the back side of the moon, greedily cartwheeling toward everything we are owed. Every day we are collecting on what’s coming to us, each day we’re being paid back for what is owed, what we deserve, with interest, with some extra motherfucking consideration — we are owed, goddamit — and so we are expecting everything, everything.

Yes, that’s how I felt. That’s exactly how I felt — I felt owed. But for a long time just afterwards, it felt like even the smallest blessing eluded me, like my early adolescence had already decided to be horrible before any of this happened and refused to divert its course on account of tragedy.

I felt broken, permanently and profoundly so, and like so many who experience trauma so young, I didn’t learn to be a person so much as I learned to cope with having to seem like a person. To find shortcuts, coping mechanisms, dangerous pleasures, things I told myself it was okay to do because I was broken and I had to get through the day. Then you wake up one morning and realize all those temporary fixes have become your permanent personality, that drinking or starving or shopping or running away isn’t what you do, it’s who you are. Do you like her?

It’s strange, carrying this story with me from person to person like jumping lily pads, just an animal with a ghost on her back. In my office, which is where I am right now, there are six photographs of him within my visual range. At my grandmother’s house there are at least a dozen in the living room, maybe more.

I’m in college in Michigan and my best friend Becky is crying big fat wet tears because her favorite dog just died, and now she is crying bigger, fatter tears while apologizing to me for crying on my lap about a dog when I’d lost a whole entire father! I get this a lot — people apologizing to me for being sad about a thing, but I try to explain that I know it’s all relative, and that even them mentioning my father at all while they’re going through such pain is so kind. See, every trauma hits you with a force relative to what the rest of your life was like. The worst thing that’s ever happened to you, whatever it is, feels like the worst thing that’s ever happened to you.

I had a friend who’d been right there in the trailer when a man shot and killed his father. I had a knack for dating boys who’d never really had fathers — who spent years in foster care or with extended family while their mothers went to rehab (or didn’t) and their fathers ran as far away as they could, usually to states like Texas or Florida. I’ve loved women whose fathers have abused them, whose fathers spent far too much time in jail, whose fathers were drunk the whole time, whose fathers kicked them out for coming out. Rebecca’s father had jumped off a bridge, you see.

It’s all relative. In many ways, I am incredibly lucky.

He didn’t feel any pain.

Are you sure? Don’t we all?

*

My Dad’s family hadn’t had much money growing up but he eventually wanted to see the whole world so badly that as soon as he started making good money, that’s what he did with it: he took us and his parents everywhere. We tagged along on business trips to Nashville, London, Hawaii, Washington DC, San Francisco. He took a fellowship at Harvard and we lived in Massachusetts for a year, visiting every historical site in New England at least once. We went skiing in Vermont and Utah. The summer before he died, he took Lewis and I to Wyoming to see The Grand Tetons and Yellowstone and we spent a day just driving across Wyoming in a rented Convertible, through mountain ranges on roads that looked like car commercials. I burnt my tiny thighs lobster-red and Dad got a speeding ticket. He got a lot of speeding tickets and had a lot of feelings about how they were all unjust, how the system itself was unjust and illogical, like how this cop was just looking for an out-of-towner who wouldn’t show up for his court date to slap with a large fine. At the start of the trip, he gave us each $10 in ones, and he’d take back one dollar every time we said “me and [name]” when “[name] and I” was correct. Mid-trip, he declared that he’d also be taking one dollar every time we talked with food in our mouths or chewed with our mouths open. We could earn our dollars back by eating raw pepperoncinis. I think we left in debt.

When he died, there was money — a life insurance policy cashed in decades early, revenue from the textbook he’d just published, other wise investments because that was what he did after all. His money paid for boarding school and college and medical bills. (I’d trade all of it to have him back.) I tried to make the money last longer by working consistently from the age of 15 on, eventually waiting tables all through undergrad, and by my mid-twenties it ran out but we had a good run. It cushioned the fall, you could say.

What I’m telling you is that in many ways, I am incredibly lucky.

In the hallway of my dormitory at Michigan, we are talking about death. Everybody is scared of dying except me. I wouldn’t kill myself, I’m just not afraid of something else happening. Chelsea wants to know why I’m not afraid to die.

When I die, I get to see my father again. I said. So either way, it’s a win-win.

A year later, I finally start going to therapy willingly. I start opening my mouth and speaking about things. His money pays for that, too.

*

In 2003 or so, a boy tells me he was googling my father and found a website about him. What can I tell you. I fell in love with the boy right that minute. And then I googled my father.

*

You know I almost think it would’ve been easier your way, says a 53-year-old friend who’d just lost her 80-year-old mother. I got so used to her being around, I don’t know how to live in the world without her. How old were you?

14. He was the center of my universe.

See, you didn’t even have time to get used to him being around! I think that would be so much easier.

I never spoke to her again.

*

It was the shock of it, you see. Ever since that day I’ve been a vigilant monitor of impending doom. I will not be caught off-guard again, nope, not me, if you’re going to hurt me I need to see it coming. The surprise of it, is the thing.

Before you know it something’s over

Suddenly someone’s missing at the table

Life changes fast

Life changes in the instant

*

On June 15th, 2007, I’m living in New York and I write in my diary: On Father’s Day, I’m going to die so I can be with my father. I don’t remember what it was like to be happy, but I’m pretty sure it was overrated. I don’t want to go anywhere or be anything. All I want is to be alone or fucked. I also don’t want to be fixed. If I was fixed, I’d want to be alive, and if I wanted to be alive, I’d lose myself. The fact that I’m alive right now is an optical illusion: everybody’s buying it.

I am hungry, bruised, exhausted, wildly hopeless. My girlfriend is having a psychotic episode which is when a person you love leaves her body and an unrecognizable monster punches itself into her skin. This monster keeps telling me that they’d seen my father in heaven and that my Dad is disappointed in me for worshipping false idols and not being fiscally responsible. It’s too much. June 17th is Father’s Day. I am reaching some kind of emotional climax, it seems, some ultimate darkness, staring my worst nightmare right in the face. Things keep getting worse and worse, line after line is being crossed. This has been building for some time.

On the 17th I have lunch with her family, and then I spend the rest of the afternoon being yelled at by a monster about things that aren’t real. The monster leaves for a bit and I sit on my stoop smoking cigarettes, drinking vodka from a water bottle. I go to the bodega for a mixer but there’d been a shooting or something and the police are there and a wailing woman and I can’t go to the bodega.

I won’t die. I couldn’t do that to my family I didn’t wanna die when I wrote that, but those have always been the only words I know that describe how this feels.

Maybe I just want a long nap, like a nap that lasts a month or two. Maybe something dead lives inside me and sometimes it starts screaming and I need to just live with that.

I sit on my stoop, drink more vodka.

I feel terrible.

I’m still here.

*

In 2008, my best friend is a liar, except I don’t know that yet. All I know is that her mother is dying of cancer and she is sad and I know how this feels so I will help. I send her the quotes from Joan Didion and Stephen Dunn. I send her long emails about grief and what happens next. She’s driving me back to my house after one of many hotel parties she threw to maintain the rich fabricated self she’d invented for us when she gets the call that her mother has died. She pulls over. She’s having trouble breathing. I drive her to my apartment, I let her take my favorite stuffed animal for a week for emotional support. I hold her while she cries.

She asks if I can help her write the eulogy and I say I can. She e-mails me stories about her Mom, I turn them into a eulogy. She says it’s really good but it needs to be longer, so I make it longer.

The invitations to the funeral she claimed to have sent us never arrive, and slowly other bits and pieces of the story she’d sold us stop checking out. This is a much longer story, a novel-sized story, this is just a small piece I want to tell you here. We look into everything and start questioning everything that’s ever happened with her. We drive to her billing address, which she says is her Mom’s mansion in Smoke Rise, and find a small apartment building. Where she lives. With her mother. Who does not have cancer, and is still alive.

I can’t get over it, I never will: You chose to fake the phone call about her death in front of me. You chose to do that in front of me, knowing that I’d lost a parent.

And this, again and again: You made me write a longer eulogy. Why wasn’t one eulogy enough eulogies. Why did you make me write a longer eulogy.

*

In 2008, I find the death certificate and I take it. It cites three hours between unconsciousness and death. I have never asked my mother about this.

*

When you get older, everybody else’s parents start dying, too. For so long, the kids in the grief group and my Mom and her half-sister were the only people I knew who’d lost a parent so at a young age, but now I know quite a few. Still it’s hard to find people who lost their parent as a teenager, and harder still to find anybody who lost a parent suddenly and unexpectedly, like I did. For that I only have television, where it happens all the time, and books.

“The dead mother thing? It’s like a club,” Rosie O’Donnell has said. “You’re initiated. You get a tattoo. It is not going away.”

When I interview Kate McKinnon, the highlight of the interview is when we talk about how nobody but us thinks dark humor about our dead fathers is funny. Or, I mean, that was the highlight for me. Probably everybody else was uncomfortable.

*

On December 25th, 2008, I write a letter to my father and publish it on my blog. It is the first time I let myself talk to him directly in public, and I am surprised that I have so much to say and I am surprised by how free I felt afterwards. (See, I believe that he read it, is the thing.)

In 2009, I turn 28. This is the midway point — from now forward, I will have been alive longer without him than with him. This means he is no longer a conspicuously absent figure in my life but a person who was just there for the beginning. Those first fourteen years become the beginning of my life, not most of my life. So there is this big life in front of me that I have to figure out what to do with.

In 2009, I decide to live. Deciding to live is the scariest decision I’ve ever made. I didn’t realize how much emotional space I’d freed up by not caring if I was dead or not. But death is not, I realize, a win-win. I have all this time, you see, and I have to use it, I have a legacy to uphold, I have to pass on his genius genes to my children. At my age he had only ten more years to live, I owe him at least double that amount. I have to show him that I was good at writing and even at business, that I started my own and made it work and that I did all the accounting myself, even though literally nobody thinks I should be doing the accounting myself. (I seem to think an MBA might be a genetic condition rather than a learned set of skills and information.)

In 2009 I get free. I become an adult. I have this huge life in front of me now. When I see him again, I want to be proud of who I am and what I’ve done and there’s a lot of things I’ve got left to do.

*

I hate Father’s Day, I just hate it. I hate Father’s Day, and Father-Daughter events, and Father’s Day gift lists, and radio ads that ask if you’ve thanked your father today. I hate that Lewis’s birthday is often on Father’s Day just like I hate that mine often coincides with Yom Kippur, when we do Yiskor, a special prayer for the departed. I hate dads who get their daughters internships and how Coach Taylor was so tender and forgiving and possessive towards Julie even though Julie was just the absolute worst. I hate the whole Father of the Bride franchise and I hate Frequency. I hated move-in day at college because that tends to be a very Dad-centric occasion and I hated Visitors Day at every camp and school I attended for the same reason. I hate when Stevie Nicks says, “This one’s for you, Daddy,” before the version of “Landslide” I have in my iTunes.

I’ve spent a lot of Father’s Days with other people’s fathers, throughout which I marvel at my own ability to emotionally detach from anything involving fathers at all. I’ve felt grateful that Father’s Day isn’t as big a deal as Mother’s Day. Losing my father made me acutely aware not only of how often the assumption is made that a child has a male and female parent, but how the idea that everybody has a mom is completely inescapable. If you’ve lost your mother, holy fuck I’m sorry, how do you get through Mother’s Day, it must truly feel like the worst.

An Autostraddle writer e-mailed us last week to ask if we’d planned any content for Father’s Day. Reader: we never plan any content for Father’s Day.

Rachel responded: I don’t think any of us thought about this because our dads are either dead or tea partiers, but if you wanted to write something I think that could be neat!

It occurred to me all at once that I could write a thing about my father for Father’s Day, even though he is dead. It’s an unpleasant topic to wade into but I’m already going through a lot of personal shit this month, how much crazier could I possibly feel? If not now, when?

I’m writing a thing about my dad for Father’s Day, I tell a friend, but I’ll probably decide that it’s stupid and too long and not publish it.

You love your dad a lot. If you’re writing it then maybe it should be written, she said. If Autostraddle is family why can’t you talk about family.I don’t think that’s stupid.

My father died when I was 14. This is the only story I can ever tell.