“Beauty and the Beast”: Disney’s Long, Slow Evolution From Gay-Coded Villains to Live-Action LeFou

Huge thanks to Valerie Anne for the Disney assist when writing and researching this post!

When Beauty and the Beast director Bill Condon said his live-action adaptation of the greatest Disney movie of all time would feature an “exclusively gay moment,” the world went a little berserk. Disney indefinitely pulled the film from Malaysia due to demands from censors, while conservatives in the United States wailed about boycotts and persuaded a least a few theaters in the deep south to drop it. I saw it in my liberal elite bubble of Astoria, New York and the audience lost its collective mind over the gay stuff (in a good way) — even though, in total, it’s a few teensy scenes that add up to about 15 seconds of movie time.

All stories matter, but Disney stories matter, you know? There’s no studio on earth whose characters and costumes and songs are so ubiquitous, so ingrained in us from the time we’re wee tiny babes. Disney movies transcend generations. We grow up on them, no matter when we grow up, and we internalize the messages we receive from them decades before we start to question how narrative shapes our inner lives and broader culture. Disney’s impact is exponential.

Beauty and the Beast isn’t Disney’s leaping off point. They’ve been doing the long, slow dance to just enough for over 50 years. Here’s a timeline of Disney’s crawl from gay-coded villains to live-action LeFou.

Captain Hook, Peter Pan (1953)

David Thorpe’s documentary, Do I Sound Gay?, traces gay-coded black-and-white sidekick movie characters of the ’30s and ’40s to the gay-coded villains of children’s stories. By the ’50, the “pansy was shorthand for gay,” film historian Richard Barrios explains in the documentary. These “sophisticated, cosmopolitan” men with “proto-gay qualities” span decades of villainy at Disney, and it all starts with Captain Hook. Peter Pan‘s big bad based on the very first gay-coded villain on the big screen: Clifton Webb’s Waldo Lydecker from the beloved 1944 noir film Laura.

Shere Khan, The Jungle Book (1967)

If Laura was the beginning of gay-coded villains, All About Eve, which was released six years later in 1950, was the film that cemented the trope. And if Eve’s Addison DeWitt sounds and acts a lot like Shere Khan to you, it’s because they were both played by George Sanders. Shere Kahn also begins Disney’s animated evolution of stereotypical gay mannerisms. He is “snide, supercilious, superior,” and the genesis of that languid, melodious villain voice.

Professor Ratigan, The Great Mouse Detective (1986)

Ratigan takes the gay-coded aristocratic villain to new heights as his fashion choices become more flamboyant and his mannerisms become even more effete.

Ursula, The Little Mermaid (1989)

Did you know Ursula was inspired by drag legend Divine? I did not! Until Phoebe kindly pointed it out in the comments! Did you also know legendary Disney composer Alan Menken wants Harvey Fierstein, who originated the role of Edna in Hairspray on Broadway, to play Ursula in the live-action remake? That’s what he told the UK’s Gay Times just this week.

Jafar, Aladdin (1992)

Ratigan was the beginning of the sibilant S in gay-coded Disney characters, but Jafar owned it, leaning into it and drawing it out like the snake at the end of his staff.

Scar, The Lion King (1994)

Much like Disney’s Golden Age, its gay-coded villainy peaked with The Lion King. Scar is the ultimate gay baddie; he literally murders a tiny, adorable lion’s giant, adorable father. Scar embraces those “little floaty cadences,” and gives those P’s, T’s and K’s all the crispness he can. He has no interest in women, only power. When he promises to practice his curtsey, Zazu shudders “There’s one in every family.”

Hades, Hercules (1997)

Hades is the natural evolution of the Hooks and Scars before him, plus: He’s literally flaming. The early aughts loved a sassy gay best friend more than anything. Hercules would have thrived on Sex and the City.

Li Shang, Mulan (1998)

No one ever says the word “bisexual” in Mulan. And no one at Disney has ever said the word “bisexual” about Mulan. But Li Shang was in love with Mulan when she was disguised as a dude and he thought she was a dude, and he was in love with a Mulan when she revealed herself as a woman. In the real world, we call that “bisexuality.” In Disney fandom, Li Shang is a bisexual icon.

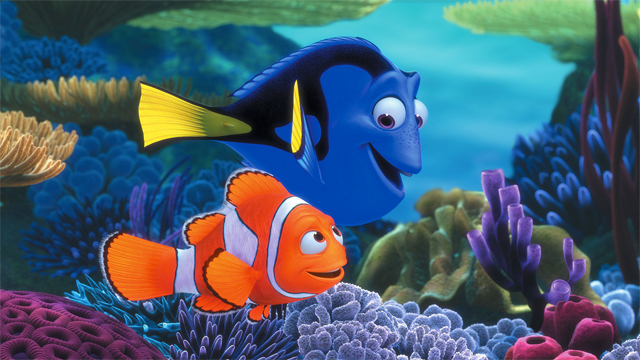

Dory, Finding Nemo (2003)

Dory may not be queer, but she is voiced by the most famous gay person in the universe. I remember seeing Ellen on a late night talk show not long after she came out in 1996 and the host asked her about the boycotts conservative Christians were threatening of Disney World since Disney-ABC distributed her show. She laughed it off and said Baptists would boycott pencils if they found out she was writing her show with them. The Religious Right made her the main target of their Bill Clinton-era culture war, but she had the last laugh, relaunching her career on the back of the critically acclaimed, eternally beloved, family friendly Finding Nemo.

Remy, Ratatouille (2007)

In Disney’s behind-the-creative-scenes book, The Pixar Touch, director Jan Pinkava reveals that Ratatouille was conceived as a coming out allegory, which makes perfect sense. He’s a rat who’s very different from the rest of his family. He’s got a secret. And when his brother finds out, his family shuns him for his desires and he leaves home to go to the big city where he can finally live as his true self. He’s Disney’s first gay hero.

King Candy, Wreck-It Ralph (2012)

King Candy is David Thorpe’s choice for worst gay-coded Disney villain. While promoting his documentary, he told the Washington Post: “He is very conspicuously effeminate. At one point in the film the hero even refers to him as ‘nelly wafer.’ (This is a play on a ‘Nilla wafer’ – a kind of cookie – and the word ‘nelly,’ a derogatory term for gay men.)”

Oaken, Frozen (2013)

Before there was the #GiveElsaAGirlfriend Twitter campaign, there was Oaken, waving to his family in a portrait. Four children and a husband. It’s a brief, blink-and-you’ll-miss-it scene, but it’s there.

Mulan, Once Upon a Time (2014)

After Mulan first revealed that she had big gay feelings for Aurora, she walked off camera and seemed to disappear like some kind of Erica Hahn into Grey’s Anatomy‘s Parking Lot of No Return. But she finally came back (years later!) for a few episodes and her friends made out with each other.

Lesbian Moms, Good Luck Charlie (2014)

During its final season, Good Luck Charlie introduced gay people to the Disney Channel. Charlie’s parents invited a kid over for a playdate and he was joined by his two moms. It threw Charlie’s dad, Bob, for a loop, but when he realized what was happening, he rolled with it. He didn’t have an issue with the lesbians; he was just surprised that they existed.

Dory, Finding Dory (2016)

Same as Finding Nemo, but Ellen had taken over the world by the time Disney got on board for the sequel. This time she wasn’t building off of Mickey’s brand; he was building off of hers.

Star vs. The Forces of Evil (2017)

Just a few weeks ago, during a dance montage, to the tune of the original song “Just Friends,” Disney aired its first same-sex kiss. Two no-name characters smooched on the lips as the camera panned by during an episode of Star vs. The Forces of Evil on The Disney Channel.

LeFou, Beauty and the Beast (2017)

If you weren’t looking for it, you might have missed the gay stuff that sent Evangelical Christians screeching toward their fainting couches during Beauty and the Beast. A quick, forlorn look when Gaston asks LeFou why a woman hasn’t scooped him up yet. Ms. Potts telling LeFou he deserves better. The smile on the supporting gay characters’ face when the wardrobe attacks him and his friends with dresses and they run away shrieking while he grins into the drag. And the very brief moment when that same guy, wearing a tux, swoops in to dance with LeFou in the final scene. It wasn’t much, but it was something real and canonical (as opposed to the speculation that came from LeFou being very clearly obsessed with Gaston in the animated film) in one of the most anticipated Disney movies of all time in a year when homophobia seems to be all the legislative rage again. Plus: Director Bill Condon insisted that LeFou have a change of heart and become a good guy before his big gay reveal. Condon also told Vanity Fair that openly gay composer Howard Ashman — who co-wrote the original film’s music with Alan Menken and died of complications from AIDS before it was released — saw Beast as a metaphor for AIDS.

Beauty and the Beast doesn’t solve our representation problems, but it’s a very welcome change of pace from the decades of homicide committed at the very well-manicured claws of the gay-coded villains of Disney past.