Batwoman #4: Smart, Feminist and Very Very Lesbosexy

Do you know how many times Batwoman issue #4 passes the Bechdel test? Five million and a gold star many times. Crime-fighting women not running around wearing stilettos many times. Female characters not being introduced by an ass-shot many times. Women not standing in awkward tit-and-ass shots many times. Gay women having sex and sweetly making out in a way that is not creepy-old-man voyeuristic many times. What I mean here is many, many times, guys.

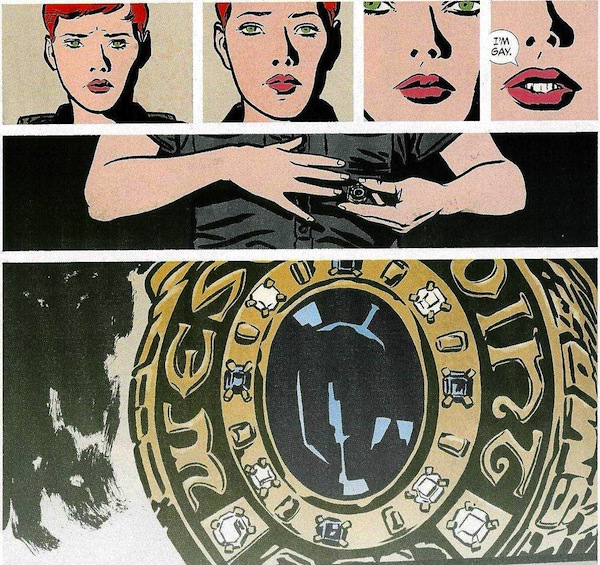

Let’s start off with why this is important: The 2011 re-booted Batwoman comic series stars an out and proud lesbian, Kate Kane, as Batwoman, and while the idea of a lesbian Batwoman might seem like a spur-of-the-moment, dank fratboy party “guys, they’re lesbians let’s watch them make out” kind of ploy, it’s not — the series stems from a brief Batwoman arc that occurred in DC’s 2006 limited series 52, where DC’s staff decided that Batwoman would be gay (and Jewish) in an effort to diversify DC’s characters. The result: A Kate Kane whose identity is so tied up in being queer that her back story, iterated on the title page of every issue of the comic so far, notes that she was expelled from the United States Military Academy at West Point under Don’t Ask Don’t Tell. The moment was illustrated with an unexpected amount of sincerity and thoughtfulness on the issue of LGBT rights.

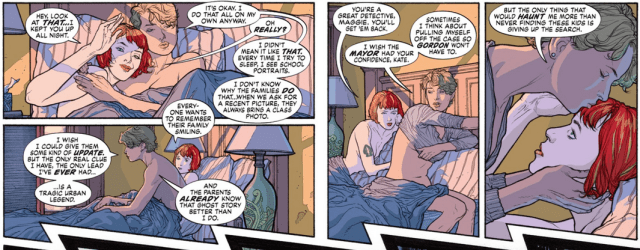

Not only is the comic tackling a lesbian main character in a way that is tasteful and well-thought-out — many of the main characters in this comic are women in positions of power and plot magnitude, from the villains to the good guys (which also means you won’t see many women functioning as undulating flesh backdrops in strip joints). It was amazingly refreshing to read Batwoman #4 — this shit passes the Bechdel test with flying colors. In it you’ll see women warning each other about getting in dangerous situations, women talking about (lesbian) sex, women discussing ongoing police investigations, women interrogating other women about dead bodies at an illegal supervillian healing clinic, women deceiving other women into divulging information — and the list goes on.

As I’m going over the comic again to recount how many times this comic passes the Bechdel test, I’m even surprised that the writers, J.H. Williams III and W. Haden Blackman, cast a woman as the main clinician at said supervillain clinic, a brief appearance that didn’t need to have a woman in the lead. But there she was.

And Batwoman has continued to surprise me. I bought all four currently released Batwoman comics to get a sense of how the story arcs are done, and while I was a little annoyed (but not at all surprised) that all the Asian characters are either thugs, dead bodies wearing dragon symbols, or smugglers operating out of a noodle restaurant, I was happily surprised by the number of Latino individuals who appear in the comic. I was skeptical at first because the Latinos in the comic are seen mainly in a position of disadvantage and victimization (the plot centers around a series of missing Latino children and their devastated families) and because the Latinos are in a position of being helped by a series of white people (-1! But who also happen to be women in positions of power — +1!).

I was pleased to see these depictions balanced out by the array of Latino characters in Batwoman #4, though — while most of the Latino individuals do appear briefly and often without a lot of personal plot focus, a central, seemingly evil spectral female character, La Llorona (“The Weeping Woman”) of Mexican legend, is Latina as well. Taken separately, the victimized Latino families and the spectral Latina villain become imbalanced racial tropes, but when put together, you can tell that Williams and Blackman are trying to flesh out a racially diverse Gotham that is not very often seen in the DC universe. The balance between La Llorona and the abducted Latino children is a little tenuous, but the effort is definitely being made not only to familiarize readers with the Latino residents of Gotham but with the cultural legends that these minority residents might be aware of as well.

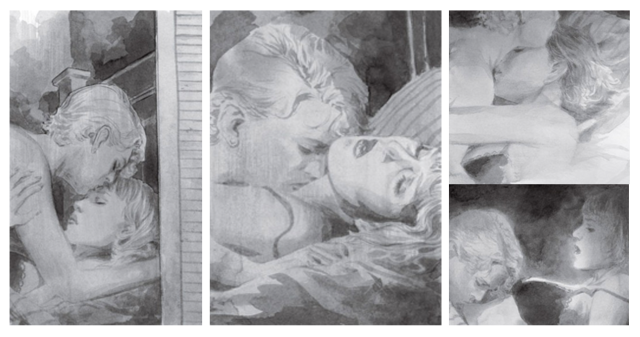

And yes, Batwoman #4 has copious amounts of tastefully done lesbian sex panels. I will just stop talking at this point and just show them to you.

Weirdly, I’m more excited about the comic passing the Bechdel test than about the satisfying amount of “O” faces that appear the comic. I know. What’s going on with me? But I think this reaction is pretty telling, because the highlight of Batwoman #4 isn’t so much women having sex with each other but the women themselves — what they do, what they say, who they talk to, who they sleep with — where the sex isn’t so much spectacle but an emotional outgrowth and fluid plot development of a well-developed romantic arc that has been progressing over the previous three issues. On top of that, the sex becomes an artistic device — it happens at the same time that something horrible and violent is happening in a completely different place, where images of pastel black-and-white intimacy are overlayed over violent, wintery, full-color imagery. The sex storyline laces all of the plots together with a sense of guilt or dread that’s likely to peak in the next issue.

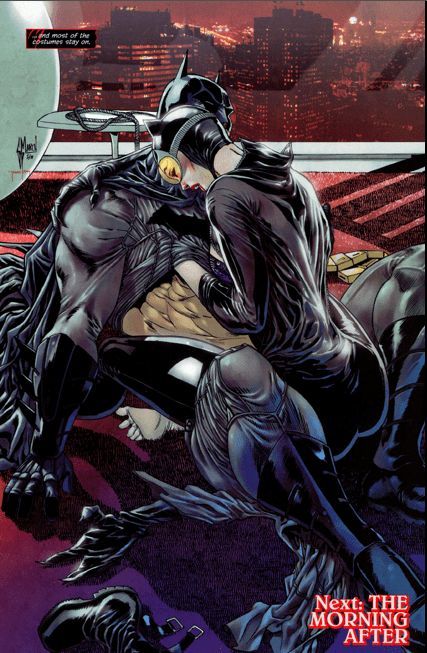

Sex happening not just for the sake of sex happening is something noteworthy, too — not only with lesbian sex, but with heterosexual sex in comics. We can compare the tasteful sex scenes in Batwoman with a distasteful and controversial heterosexual sex scene that appeared in Catwoman Volume 4, issue #1, also published by DC Comics, where in the final panel of the issue, the title character does it on a roof with Batman. No smoke. No mirrors. Just penetration. It’s so gross I’m not even sure about the physical possibility of what’s happening here — why are they positioned like that? How on earth is pole A positioned so that it can go into hole B? How on earth are her tiny inhumanly disproportioned legs managing to go all the way around that massively steroidal Batman man-torso?

But the main question is, though, why do we need to see that? Laura Hudson discussed the comic on Comics Alliance asking the same question: “What does it accomplish or tell us about the characters that would have been lost if that page had been omitted? The answer is nothing.” This is what happens when sex serves the purpose of being sex — it becomes gratuitous, kind of creepy, not very important, and it becomes an issue of sex being catered to the desires of the audience rather than the characters themselves. And when sex ceases to be something owned by the characters and their emotional arcs, the comic becomes kind of trashy. And I’m relieved that when I flipped through the pages of Batwoman #4 none of the normal red lights crossed my mind — why is this here? Why is this important? Why am I looking at this?

The work that Williams and Blackman are doing on the new Batwoman isn’t perfect, but it’s definitely moving the depiction of gender, sexuality and racial identity in mainstream comics in a direction where tokenism and spectacle are no longer king —instead, the fleshed-out portrayal of well-developed and diverse main characters, side characters and sub characters matters more than a diversity quota. The comic has handled Kate Kane being a lesbian exceptionally well, putting her into a class of superheroes where her emotional arcs are conducive to fitting romantic and sexual plot lines. The (male) writers’ attempts to understand what it’s like for a queer woman to patrol Gotham, to be expelled under Don’t Ask Don’t Tell and to have a fulfilling romantic life with other crucial Gotham characters is also touching and real — Williams and Blackman are making a huge effort, and it’s obvious and greatly appreciated.

TL;DR: Go buy the comic and support Batwoman.