Autostraddle Read A F*cking Book Club #1: Eileen Myles’ Inferno

All night I struggled and tugged for the perfect word. In the brown of the dark, my sister’s soft breathing in her Hollywood bed across the way. The hum of the house, the oil heater that might blow up. Groaning, stopping, going strong. Devil shaking the bottom of my bed when I closed my eyes. (p 75)

I didn’t know what “a poet’s novel” meant when I started reading this book. I think I thought it just meant “a novel written by a poet” or “a novel with poetic tendencies.” That is not what this is, I don’t think. I think what Myles meant when she called this a “poet’s novel” is that it is a novel built the way that a poet builds a poem. It’s one structure inhabited by another. I get that now. I think I get poetry in a way I didn’t before, or at least Eileen Myles’ poetry. Eileen Myles. Goddamn.

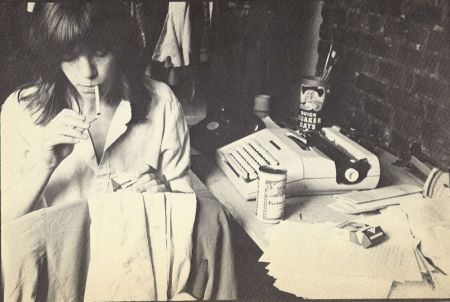

As I should maybe have intimated from the subtitle, the technical aspects of this novel are really important; a lot of the writing in it is in fact about writing, which had me thinking about the writing in the novel itself really intensively in a self-referential and kind of exhaustingly “meta” way. The book opens in an English class, dissecting literature, and I feel like the whole way through you can feel Myles performing that same kind of dissection; her presence is still tangible in each line, you can feel how she’s pruned and perfected each sentence in the way that poets do. When you think about it that way – as almost an epic poem instead of a novel – it makes the whole thing seem just sort of staggering and crazy, intimidating but amazing.

I think what was also really intimidating was her total lack of self-pity. It felt like she really was writing about a character in a novel sometimes, like she was just sort of mildly fascinated with the trials of this hungry, brilliant young woman selling lead slugs for beer money. As Emily Gould says in this show, “Eileen Myles for President,” by the Poetry Foundation that I’m now obsessed with, “…as she’s refusing to group herself with the people who’s memoirs are “Look how badly I’ve been victimized,” she’s saying, “well, you know, I have of course been victimized, but that’s not the point.” As she puts it, there’s no self-pity in Eileen Myles, but she does want you to know.

It felt like such an extraordinary act of self-control or of complete dissociation to be able to just put this here, to put all these things that happened on pages in ink and then leave them without trying to fix them or explain them or defend them or heal them. Everything she went through, everything anyone did to her is just here. Every feeling she had of incredible confidence that another woman might feel verged on cockiness — that’s there too. She is unapologetic. How do you do that, how do you give us these things without giving us your heart and soul along with them. It amazes and terrifies me.

My corrupt womanhood: a waste. I feel the same way about being a writer. Staying up all night burning my brain cells, for years, swallowing tons of cheap speed, also for years, eating poorly, pretty much drinking myself to death. And then not. Contracting whatever STD came to me in the seventies, eighties, nineties, smoking cigarettes, a couple a packs a day for at least twenty years, being poor and not ever really going to the doctor (only the dentist: flash teeth), wasting my time doing so little work, being truly dysfunctional, and on top of that, especially my point, being a dyke, in terms of the whole giant society, just a fogged human glass turned on its side. Yak yak yak a lesbian talking. And being rewarded for it.

Somehow her lack of sympathy for herself made it worse, made me feel for her even more. I was conscious of feeling really sad that she had been young in that time and that place, when it was so hard to be a woman and be an artist and be gay and be all those things. Like how awful must it be to have to feel like being gay is like diving into cold water, like you have to put it off for as long as possible and then brace yourself and grit your teeth and say “well, I guess I have no choice” and let yourself drop like a brick. Good thing that’s over with – and then I was like, oh wait. I see what you did there. I felt even sadder about that.

Did you notice how it felt less and less like a novel as it went on? Like I felt less like there was a character called Eileen/Leena/Ei and more like Myles was addressing me directly. Fourth wall or something. I felt like as the book progressed it became less preoccupied with a character or story and more preoccupied with stories in general, or with art, I guess. She gets so vocal about supporting art and artists, about how hard it is to find someone to give you money for your work.

Aside from being confused and blindsided by this shift in genre that made me feel like I was maybe crazy, I was also just kind of bewildered by this concept on a basic level. I think I grew up with the belief that being an artist means you deserve to be underpaid and underfed and overworked and underappreciated. I was so impressed but also weirded out by her balls-out assertion that she deserves to be paid for her work like anyone else, that she deserves to make a living off what she lives for. She writes in “An American Poem” that “My art can’t be supported until it is gigantic/until it is bigger than everyone else’s.” I don’t know what that means. This is what I wrote in my journal:

she gets into this space where art is important, where art is worthwhile, maybe the only worthwhile thing. i both dislike and admire that; the ability to get into your work, whatever that work is, so much so that you feel like you can demand attention for it. and compensation. i am astonished always when anyone feels like they deserve anything, because i so rarely do… it was nice because for a minute it took away the sense of why do we do this even; i was able to stop thinking about the overarching anxiety that is the self-indulgence of making art. it just seemed like a thing. like building a house. or making a dress. you just make this thing to put in people’s hands. even if it’s only your own hands. and i hadn’t realized what a relief it was to have that question taken away. how much easier it makes it to concentrate on other things, like how you can make this the best thing it can be.

That was probably oversharing. This is what Riese wrote in her journal:

Reading Inferno has been good for me. Like the opposite of being yelled at for not taking a $10/hour office job ‘just to do it’, like I hated that moment. I would rather be hungry and owe visa than do a thing besides the point. nobody has to understand it, but they do because if they don’t understand it, they won’t support it. art is the most important thing, but people don’t think they should pay for it. instead they pay for things they hate. accountants and orthodontists. people will pay for art, you just have to ask them. like not feeling guilty to run on donations sometimes but I do. This is what makes the unemployment/constant hustle bearable to artists — they value the experience of striving, they almost need it. this is our job. it is our job to work weird jobs and to beg. Why do I feel guilty for wanting to write instead of file. I file too.

In any case, I was really impressed by this book, in the same way that one might be “impressed” by a moving car if they step into a crosswalk without looking both ways first. It made me think really differently and write really differently while I was reading it, which is pretty much my measure of whether a book is good or important or well done. I don’t know that I really “got it,” or at least all of it, but I don’t mean that in a way that means the book is pretentious or intentionally obscure or impenetrable. Just that some things take a long time to tease open and work out, and that doesn’t mean anything bad. On the contrary, I feel like it is often good for books to be hard, to stretch muscles and leave you kind of sore but happy afterwards. That is kind of how I felt after reading Inferno. Tired and sore, but happy.

Here is what some other people have to say about this book.

+ Gloria Woodman at Terror People: “It’s a nice book to have. The cover is swirled with static flames and the type and layout make it easy to read. Even drunk in this Laundromat. There is something powerful about Eileen Myles’ writing, evenInferno (A Poet’s Novel), this almost trite re-telling of her other work. It doesn’t matter what she is saying, I want to listen. I want to hear her stories over-and-over again. She writes about seeing a picture of Amelia Earhart, “I couldn’t tell if I had a crush on her, or was her, or if I was just crazy.”

+ Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore at Bookslut: “Inside Myles’s castle, everything is pared down even when it’s rambling and raw and rough and broken and shy and bold and open: “We were so excited because the silence of our childhood was over…” Inferno shows us the adventure of poetry, but also reveals the places where a poet starts to philosophize absently: do we really need to know that the “quality of people’s togetherness” is called a bhav in Bhakti yoga? Instead let’s stay in that space where the page becomes your head, expanding.”

+ Herocious at The Open End: “Reading INFERNO was bodily, it jerked my mouth around and made me jot down words in the margins. This way, they could snug close to Eileen’s prose.Fanning through the pages with my thumb – after reading it – I couldn’t help but stare at my scratchy notes and silently understand how much the INFERNO experience stimulated me, a high point in my life as a reader. The idea of replicating that experience in a strained and articulate review made me ball up in the corner and scream.”

+ Liz Brown at Bookforum: “With Inferno, Myles has written, among other things, a field guide to poetry readings—the “trembling voices,” the crowd “laughing familiarly”—as well as a meditation on hatching a writing life. She offers theorems about relationships with the famous, the artist’s responsibility “to get collected,” and how rich people need poor friends. In charting her downtown travels, she has mapped a bygone New York: Club 57, the Pyramid, and the Duchess, the dyke bar where she drunkenly attempts to do the splits. The book, in other words, is packed.”

What about you? Tell me how you feel. Use examples from the text. I wanna know.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS!

1. Is this a novel? Or an autobiography? Or a memoir? Does it matter?

2. Was it weird how honest she was about real people/events? Good? Bad?

3. Can we talk about what I am calling “the vagina chapter.” You know the part I’m talking about. I wanted to talk about it here but I didn’t know how. I trust that you will.

4. Did you, like, know about Eileen Myles before this? If so, has anything changed in your feelings about/for her? If not, what are your thoughts?

5. Did you feel a little bit insane after reading this book? I did, it’s ok.

Rumi had someone following him around all day long, while he spoke the poem. He was simply in it. I was in it too. The room was the poem, the day I was in. Oh Christ. What writes my poem is a second ring, inner or outer. Poetry is just the performance of it. These little things, whether I write them or not. That’s the score. The thing of great value is you. Where you are, glowing and fading, while you live.