Autostraddle Book Club #4: Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic

So, honestly, I start out with the same feeling every single time after finishing these books, which is “I can’t talk about this.” And then I experience a second, corollary feeling which is “I don’t know how to talk about this without talking about me. I don’t want to talk about me.”

But I think this time I actually don’t know what else to do. I am literally incapable of talking about a memoir about a queer woman grappling with a fraught, distant, infuriating relationship with her father without talking about myself. See, the thing is, I read almost all of this book while my father was, in fact, visiting me! My father and I see each other 2-3 times a year, and there is always at least one other family member present to act as a buffer. But not this time. Also, since I now live alone instead of with a house full of roommates, he didn’t see any reason to stay in a hotel, and instead slept on an air mattress in my tiny one-bedroom apartment. So weirdly, but I guess appropriately, this book was the only companion I had. I read it in an armchair while he read his Bible (which he carried with him from ten hours away) on my couch, and I read it alone in my bedroom while I listened to my dad fumble with the kitchen light and the wine bottle in the other room. It was, I guess, a lot sadder because of that — because I couldn’t read it like it was a story, something outside myself. But it was comforting, for the same reasons.

It feels a little weird to call Fun Home a memoir. I guess I don’t know why I do — the books calls itself a “Family Tragicomic,” and you could definitely argue that it’s more a book about Bechdel’s father than Bechdel herself, which I guess is what a memoir would be. But even if you leave aside the gay — the fact that Bechdel discovers that her father has had affairs with men (and some of his male high school students) that coincides awfully with her own realization that she’s a lesbian — this is kind of a book about the way in which Bechdel’s own story and her father’s are inseparable, or at least how it would be difficult to tell the former without telling the latter.

There is something about being a tomboy, about the father-daughter relationship that grows out of that. If you are lucky enough to have a father. If you are lucky enough to have a relationship. Which Bechdel was, and which I was. Sort of. Maybe this isn’t everyone. But I remember the time when I was eleven years old, and a woman in the mall was trying to recruit girls passing by for some sort of ‘modeling program.’ She tried to hand me a card, and asked “Have you ever wanted to try modeling?” I said no. My dad was so proud, clapped me on the shoulder for being his little girl who didn’t care about being beautiful. Years later, when my brother wanted to get his ears pierced (I think he wanted big fake diamond earrings like a rapper’s, it was very on trend) my father said no, never; it wasn’t what boys did.

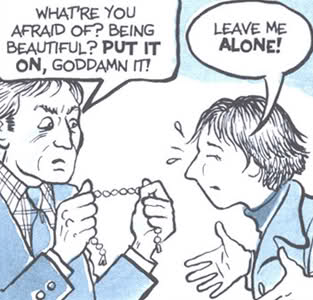

That’s not how it works for Bechdel and her father. He wants her in dresses; he wants her to look nice enough to be a credit to him, something beautiful that he made that he can be proud of. And he is proud of her, of her brain if not her outfits. “You’re the only one in that class worth teaching,” he says when she ends up as a student in his high school English class. And she says, “It’s the only class I have worth taking.” There’s something there, there’s something in there that only a reticent father and a moody teenage daughter can give to each other. Some kind of approval, reciprocal admiration. Something that we don’t actually get, I guess.

Bechdel’s father is dead. He dies, he died, when she was in college. Younger than I am now. He killed himself, or so the evidence would suggest. Which changes everything, which defines everything. Because Bechdel is left to imagine his life as it could have been, but maybe even more so to imagine his life as it was. Filling in the blanks. There are a lot of blanks. She has his letters, and we see them too, but those aren’t the whole story. If there’s one thing we learn in Fun Home, one thing that Bechdel herself knows even as she’s writing a book, it’s that the things we write are more about what we want to be true than what is. We write things for a lot of reasons but not necessarily because they’re true. When the only thing you really know about someone is that you don’t know the truth about them, how do you remember them?

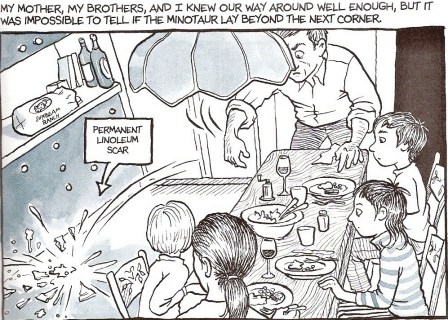

It would be easy, in a lot of ways, for Bechdel to cast her father as a villain. He’s distant, he’s duplicitous; he’s angry. He hits her and her brothers, he throws things. He buys beers for minors to seduce them. He commits suicide and leaves no note. Maybe that’s the worst part of all. And she holds him accountable for that; there’s no denial of responsibility for the things he did, and the things he didn’t do. But she finds some responsibility for herself, though, too. Accurately or not, fairly or not. “If I had not felt compelled to share my little sexual discovery, perhaps the semi would have passed without incident four months later.” Because that’s the thing about dads, right? Somehow nothing that they do to us, or don’t do for us, is quite as bad as our refusing to forgive them for it. There’s a weird sense of contradiction throughout, one that is completely honest even when it seems insupportable: the lack of emotion that Bechdel is able to summon about her father, but her simultaneous preoccupation with him and the huge way in which his short life still informs and occupies her own. Bechdel talks about how grief can take the form of its absence; the sadness that builds up over the course of a life until it’s so big that it eclipses the sadness of death.

“It’s true that he didn’t kill himself until I was nearly twenty. But his absence resonated retroactively, echoing back through all the time I knew him. Maybe it was the converse of the way amputees feel pain in a missing limb. He really was there all those years, a flesh-and-blood presence steaming off the wallpaper, digging up the dogwoods, polishing the finials… smelling of sawdust and sweat and designer cologne. But I ached as if he were already gone.”

This week my dad picked up a framed photo off a shelf in my apartment. “Are these your friends in your [graduate] program?”

“No, Dad,” I said. “Those are my old roommates? I lived with them? Remember them? You’ve met them.”

“Oh,” he said. After my dad left, on a Monday morning, a friend of mine asked “Do you miss him?”

“No,” I said. “We’ve gotten along a lot better since we moved far apart.”

“I meant now,” my friend said. “Like, since he’s left.” The thought hadn’t even occurred to me. What was there to miss.

There’s a sense throughout that Bechdel is angry at her dad. The image of her sitting next to the phone, bored while her dad rhapsodizes over Joyce on the other end of the line. It’s so familiar, it’s a perfect image. (And a nice example of why this is so great as a graphic novel — when I close my eyes I still see cartoon-Alison in the fetal position on her dorm room floor as her mother tells her about her father’s secret, and the giant looping attempts at obscuring her own record of her life.) And why shouldn’t she be — he lied, to her and to her family, he embarrassed them in front of the entire community, and he alternated between distant and aggressively controlling, with only occasional instances of tenderness. How could you not be angry. And so she is, but you get the sense that’s not the core of it, that’s not really where the anger comes from.

Maybe more than anything else, the book is a study of a virtual stranger, a profile of someone who was always just out of reach, assembled from found objects and remembered evidence. Going through a box of old things, she discovers a photo of her father posing in a women’s bathing suit — there are no clues, no context, but he looks like maybe he’s enjoying it, like maybe he feels good. Years later, (presumably) without her father’s knowledge, Bechdel and her friend dress in his suits and ties to be pretend to be slick con men. Dirty Harry cool, James Bond aloof. “Putting on the formal shirt with its studs and cufflinks was a nearly mystical pleasure, like finding myself fluent in a language I’d never been taught,” she writes.

Bechdel’s dad died before she ever had a chance to know him, before he had a chance to know who she would grow into. That’s something to be angry about. Even if he had lived, he still wouldn’t have been present in the way she needed him to, wouldn’t have known her as deeply as he should. And no matter how long he lived, she would probably never have really known him. “We were close. But not close enough,” she says.

I hold my dad responsible for a lot of things that I find hard to forgive; some fairly run-of-the-mill, especially if you’ve ever been to divorce court, and a few that are less ordinary. He actively attends Tea Party meetings, believes that homosexuals should be prevented from having access to young children aka being Boy Scout leaders, and tried to convince me to break up with someone because the color of their skin as compared to mine was “dangerous.” We have a list of things we don’t talk about: politics, religion, the Middle East, almost every other member of our family. I can’t pretend I’m not angry. But I think the worst thing, the thing that I actually can’t forgive, is that we spent four days together and ran out of things to say to each other at the 1.5 mark. He left my apartment while I was at work, and he didn’t leave a note. I didn’t look for one when I got home. He’s not the only one with a questionable claim to forgiveness.

Thinking about how her desire, ambivalent as it may be, to “claim” her dead queer dad, Bechdel writes “Erotic truth’ is a rather sweeping concept.” Then she says “I shouldn’t pretend to know what my father’s was.” Every single time I read that line, it reaches me as “I shouldn’t pretend to know who my father was.” I guess that’s right, too.

That’s all I’ve got. Now it’s your turn.