On the Front Lines: Alternative Forms of Protesting Police Violence

featime image via BC Art Life

This piece was originally published on 1/20/2015.

George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020, and we stand in unequivocal support of the protests and uprisings that have swept the US since that day, and against the unconscionable violence of the police and US state. We can’t continue with business as usual. We will be celebrating Pride as an uprising. This month, Autostraddle is focusing on content related to this struggle, the fight against white supremacy and the fight for Black lives and Black futures. Instead, we’re publishing and re-highlighting work by and for Black queer and trans folks speaking to their experiences living under white supremacy and the carceral state, and work calling white people to material action.

Here at Autostraddle we’ve done a fair amount of coverage of the recent protests swelling around the issue of police violence and systemic racism. We’ve also covered how queer and trans women of color are often both at the center of violence from the police and prison system, and at the same time on the front lines of the protests to stop it. For people who want to see change, we are full, heavy, and undone by the outpouring of support in the streets. We feel as though, perhaps, we are on the brink of revolution. But many of us haven’t been on the literal front lines. Not for lack of rage or revolutionary spirit, but because our advocacy comes in many forms.

A friend of mine, an arts activist who is a theater-maker and who works a low-paying job serving coffee to wealthy fifth avenue suits, was on her way to work when a protester stopped her and demanded to know why she — a woman of color — was not in the streets demanding justice. Her answer? “I have to pay rent.” A luxury for many protesters is having a warm home to return to at the end of the night, a home for which somebody probably pays rent. Speaking of payment, getting arrested often precludes paying a fine, or bail, or having a friend or family member to call who can come pick you up. What if you are homeless, or estranged from family? What if you have a job that would not be patient if you are late or absent because you spent the evening at Central Bookings? What if you are physically unable to attend a protest because you use a wheelchair or otherwise disabled? What if you just don’t want to chant and march through the streets in the bitter cold?

Friends and family have leadingly asked me, “so did you ever go to the protest?” as though if I hadn’t, I was doing a disservice to our race. I know of other POCs who couldn’t bring themselves to protest because the very weight of the perpetual onslaught of depressing headline after depressing headline left them feeling emotionally weak. But I have found that those same people, wracked with guilt, have contributed in their own ways, sometimes unwittingly. After the first few nights of emotionally charged spontaneous protests broke out in New York, Autostraddle’s very own Gabby Rivera organized a Google hangout session for QTPOC Speakeasy members. We expressed our outrage, our exhaustion, as well the humor that might seem inappropriate to an outsider, but which was so very necessary if we were to have enough stamina to face the day. During the hangout, we came to the realization that what Gabby had done for us was community care. She was affecting change by giving others a place to prepare themselves to affect change. That is valuable. It’s not as visible as attending a march. There were no selfies to prove we had been there. But it had tangible value.

Alternative forms of protest are necessary to make activism accessible. Sometimes, they’re even more effective at creating change than a permitted march. Here at Autostraddle, we have heard from readers far and wide who say that the content on this website has given them a sense of community they couldn’t find elsewhere. I mean, not to toot our own horn but that’s freaking incredible! Where better to convene a mass of rad queers than on the web? Where better to plot the revolution? If you are feeling bummed about not being able to, or not wanting to attend a protest or a die-in, you don’t have to be. There are a myriad of ways you can contribute, and you might already be doing it without knowing.

When petition sites like Change.org started popping up, there was a lot of skepticism surrounding the effectiveness of a petition that was just too easy to sign. Long before any of these phenomena, “Facebook activists” were taking advantage of easy access to hundreds and thousands of people to disseminate information from independent and alternative news sources, to the annoyance of some, but the benefit of many.

Now, the positive effects of cyber activism are becoming clear. Petitions on Change.org and other sites have countless success stories. I first heard about the Michael Brown case from a Change.org email. I know many others who received this tragic news the same way. This was amidst the End Stop-and-Frisk campaign taking off in NYC, and I believe the confluence of these two events have inextricably tied Ferguson to New York, even before the police murder of Eric Garner. Something as simple as signing up for an email listserve brought the Michael Brown case to the doorstep of every American, and helped galvanize a nation. Previously, the memory of Michael Brown would have been reduced to a statistic.

Entire revolutions have been facilitated via Twitter and Facebook. American movements have taken a page from their book, using Twitter to locate protests in real-time without alerting the authorities. Other hashtag movements have given a voice to those usually marginalized. For example, the twitter-facilitated movement, #YouOKSis encourages women, especially women of color to be active bystanders in instances of street harassment, and to share those experiences on twitter. Creating a community where women of color know they can rely on others to check in and prevent potentially violent interactions in the street can offer peace of mind to women whose voices are often drowned out by the patriarchy.

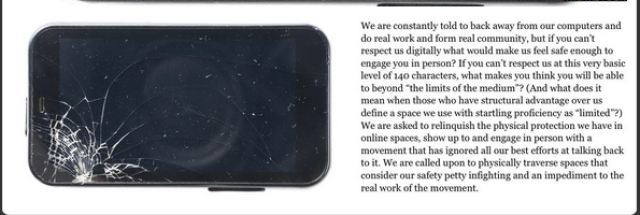

Speaking of creating space, #ThisTweetCalledMyBack recently came to the defense of what has been dubbed “Toxic Twitter.” Toxic Twitter refers to primarily POC women and marginalized communities that have found their voices in the Twitterverse:

We are your unwaged labor in our little corner of the internet that feeds a movement. Hours of teach-ins, hashtags, Twitter chats, video chats and phone calls to create a sustainable narrative and conversation around decolonization and antiblackness. As an online collective of Black, AfroIndigenous, and NDN women, we have created an entire framework with which to understand gender violence and racial hierarchy in a global and U.S. context. In order to do this however, we have had to shake up a few existing narratives…

The response has been sometimes loving, but in most cases we’ve faced nothing but pushback in the form of trolls, stalking. We’ve, at separate turns, been stopped and detained crossing international borders and questioned about our work, been tailed and targeted by police, had our livelihoods threatened with calls to our job, been threatened with rape on Twitter itself, faced triggering PTSD, and trudged the physical burden of all of this abuse. This has all occurred while we see our work take wings and inform an entire movement. A movement that also refuses to make space for us while frequently joining in the naming of us as “Toxic Twitter.” Why do we face barriers at every turn? If you hear many tell it, we are simply lazy women with good internet connections.

In an age where young women often have cell phones with internet access before they have access to healthcare and social services, why are so many so quick to demean the work of digital feminism in the hands of Black women?… When we ask these questions, we uncover that the only people who meet these qualifications of real activism are cis gender, able bodied people — frequently male.

Online activism is controversial, no doubt. “Hacktivism” is often synonymous with the vigilante hacker organization Anonymous, which has achieved many things by threatening to reveal the personal information of their targets. Often these targets are the subjects of high profile controversies, like the Westboro Baptist Church, or members of the KKK. More recently, Iggy Azalea has been the subject of Anonymous’s ire, after she got into a rather sticky (read: racist) twitter argument with Azealia Banks surrounding the issues of cultural appropriation and solidarity with Black people. The group threatened to release leaked sex tape photos and called her a “trashy bitch.” This kind of misogynist and childish behavior begs the question: who deserves privacy? While we all cower in fear of the elusive NSA, we often applaud Anonymous’ threats because they have progressive ends. But is it really progressive to lord over misguided individuals by threatening to distribute pornographic images of them? Vigilantes not associated with Anonymous, but with the same skill-sets have released nude images of famous women, not-so-famous women, and women who have dared to speak out against misogyny or rape culture. Hacking is a powerful weapon, often misused in the wrong hands. But then, what revolutionary tool doesn’t have the capacity to be misused?

Sometimes art can be more engaging and transformative than a rally or march. Sometimes art has the power to affect more minds than a riot. Theatre of the Oppressed (ToO) is a revolutionary form of theater that teaches visual literacy, and gives oppressed people a platform to not only express their grievances, but address them as well. The creator of ToO is Augusto Boal, a Brazilian man who considered this technique a sort of rehearsal for real life. One of the many forms of ToO is a performance called Forum Theatre, in which members of a community act out a play that describes their predicament, with a protagonist, antagonist and supporting characters. The audience is then invited to “intervene” in the action of the play, performing the piece over and over until a solution is developed that can then be acted out in real life. ToO groups in New York City do a version called Legislative Theatre in which actual legislators participate alongside citizens and social justice organizations to develop policies. In May of 2014, Theatre of the Oppressed NYC put together a legislative theatre festival addressing racism and profiling within the criminal justice system, called Can’t Get Right. Spect-actors (as Boal called participatory audience members), were invited to “watch, act and vote” alongside city policy-makers on reforms that would improve quality of life for Black and brown citizens of New York. In no uncertain terms, this is revolutionary: giving people the tools to be the change they wish to see.

I have heard some compare the recent protests to what it felt like to live through the Civil Rights movement. While I can’t personally attest to that, nostalgia for the revolutionary spirit of the Civil Rights era does seem to be in the air. And with it, have come reworked, or brand new protest songs. Remember when Lauryn Hill came out with Black Rage? The AP recently reported on the resurgence of protest songs from the rank and file protesters, poets and songwriters. And then D’Angelo released his album Black Messiah, with a tribute to brothers and sisters in the struggle:

Black Messiah is a hell of a name for an album. It can be easily misunderstood. Many will think it’s about religion. Some will jump to the conclusion that I’m calling myself a Black Messiah. For me, the title is about all of us… It’s about people rising up in Ferguson and in Egypt and in Occupy Wall Street and in every place where a community has had enough and decides to make change happen. It’s not about praising one charismatic leader but celebrating thousands of them.

Hip Hop and Black music have always had a sociopolitical undercurrent, but it does seem that we’re developing a soundtrack for our revolution — and it’s sounding pretty funky.

Beyond the web and the stage, there are unlimited ways to contribute our time, energy and money towards a world we would want to raise our kids in. Economic boycotts have been a major part of the anti-police violence movement. Temporarily hindering the economy sends a big message to companies that tend to ignore the plight of the very people they probably employ.

While the alternatives to protest discussed here are by no means all-inclusive, hopefully they’ve inspired you to employ the skills I know you’ve got tucked away in that gorgeous, complicated, infinite brain of yours to do something particular to your interests. If you really don’t know where to begin, Tikkun.org has released a flyer detailing exactly 26 Ways To Be In the Struggle Beyond the Streets. Some of my favorites off the list include providing childcare to protesters, and cooking a pre or post-march meal. Whichever way we choose to participate in this movement, it is important to recognize those who came before us and amplify the voices most often silenced. If we follow those two rules, no form of protest is necessarily more or less valuable than another.

Talking with Reina Gossett and Grace Dunham About Everyday Activism and Why Empathy is Everything

When I met with Reina Gossett and Grace Dunham to talk about activism, the LGBT community and the ways they’re working to change the world, it was immediately obvious how much they love one another: truly, platonically, mutually, completely. The camera isn’t running and Gossett has left the room when I comment on how slickly they finish one another’s sentences. “Well,” says Dunham matter-of-factly, “Reina changed my life.” And this becomes the overarching theme of our conversation: how interpersonal relationships can be more transformative than Big-A Activism. I had heard about their close relationship, and how it was informing some incredible work together, so I sought them out to find out more — over the course of our afternoon together in NYC, our conversation covered everything from the damages of biological essentialism to the radical power of empathy to how important it is to feel sexy sometimes. Though the duo cover every topic from transmisogyny in the lesbian community, to empathy and self-examination, to filmmaking, the major takeaway from our conversation was how interpersonal relationships can be the breeding ground for empathetic, transformative, revolutionary acts of everyday activism.

Grace Dunham (who uses both she/her and they/them pronouns) and I met when we were 12 at St. Ann’s School in Brooklyn. Despite a reputation for whitewashed privilege, a pervy founding headmaster and an extremely competitive college admission process, St. Ann’s is a safe space for strange kids — a unique departure from most of New York’s elite prep schools. Our friendship was shortlived, because as soon as I found my niche of weirdos, I realized Brooklyn Heights wasn’t ready for this jelly, and I bounced on out of private school. Years later, when Grace’s sister Lena created the breakout hit Girls, I found myself wondering what had become of them. Grace had a reputation at St. Ann’s as a phenomenal playwright; their graduation speech had been re-published and circulated for its succinct and impressive rhetoric. Certainly she had a platform from which to project her voice, so why hadn’t we heard from them yet?

And then a whiskey-fueled encounter at a local Bed-Stuy queer haunt, One Last Shag, brought us full circle. There we were, nearly fully realized gay grown-ups: I, a writer for the dopest queer lady publication this side of the Atlantic, and Grace traveling the world to bring awareness to feminist and trans issues. I learned that Grace had been working with The Reina Gossett, the silver-tongued trans activist whose name and work is tossed around feminist and prison abolitionist communities more often than the word “intersectionality.” The duo had been traveling the country, researching, learning and storytelling about the history of cross-dressing laws, transphobia in the queer community, building community through nightlife, all while trying to live authentically as queer friends in the public eye.

I asked if I could talk to Gossett and Dunham about their work, and so a week before Pride, we were three queers on a couch overlooking New York City, home of the Stonewall Riots. In the weeks before our interview, Grace mentioned that their research is partially focused on identifying and critiquing transphobia and transmisogyny in the lesbian community. We know it’s there — the transphobia — but the circles I run in deny it vehemently. I hear about these radfems who make a big stink about excluding AMAB women all the time, but I’ve never met one. As a person who thinks about race and racism a lot, I think it boils down to this: just because you don’t ride around rocking a white sheet, doesn’t mean you aren’t racist. Similarly, just because you don’t go around bashing trans women doesn’t mean you aren’t transmisogynistic. Everyone’s a little bit racist. And we’re homophobic, transphobic and classist, too. Gossett and Dunham are committed to recognizing the ways state violence and oppression move through us, even as (or especially because) we push away from it.

For clarity, the oppression of trans women and AMAB gender-nonconforming people is a symptom of transmisogyny, which occurs at the intersection of transphobia and misogyny. However, Gossett was very clear about why they often choose to use the term “transphobia” in place of or in addition to addressing transmisogyny.

“It’s important to me to say not just transmisogyny but also transphobia,” Gossett said. “The same kind of biological essentialism that says trans women should not be in women’s spaces, or that so comfortably uses biology to define what it means to be a woman, or so comfortably uses unreflective and frankly white supremacist and transphobic ideas of being ‘socialized as a girl or socialized to be a woman,’ so often allows trans men or female assigned trans people to take up space. Why? I think because they are using a biological essentialist understanding of what gender is and… I am just so over it!”

For Reina, transphobia refers to our tendency to discriminate based on outward appearances; a tendency which has reproduced violence in the most horrible and dehumanizing ways possible. The same tendency to privilege what we perceive to be male is the same tendency that devalues what we perceive to be female, all of which is an entirely fabricated social construct. Reina identified one major event as an example of how violence reproduces itself.

“In 1973, for instance, this organization called the Lesbian Feminist Liberation [LFL], was really dealing with a lot of sexism within the ‘Gay Movement.’ And they were like ,’This is not okay, there’s so much sexism and we need to stop this. We need to form our own organization.’ So, at the 1973 Pride, Sylvia Rivera gets on stage and starts talking about the Gay Movement forgetting about trans people in prison — and queer people and gay people in prison. At that same Pride, LFL was handing out pamphlets saying that trans women are a mockery of women — specifically, trans women who are getting any kind of income or have a monetized relationship to being trans. I think that is still deeply rooted, in at least queer communities, and has definitely largely affected my experience.”

“I think that it’s complicated in that visibility doesn’t necessarily in and of itself stop violence from happening.”

A major issue here is visibility. “I think that it’s complicated in that visibility doesn’t necessarily in and of itself stop violence from happening,” says Gossett, a point she has made time and again in public appearances. “In fact visibility can be a big form of violence, and something they don’t get to choose… and not bring with it material or emotional or soulful or energetic positivity or liberation or things that help you live day to day.” This consistent pattern is why so many queers are concerned that the recent marriage equality ruling is actually a major setback for other sexual and racial minorities. For this very reason, Gossett and Dunham are concerned with examining social movements prior to Stonewall; prior to “visibility.”

This idea of queer and trans community pre-Stonewall is a major point of interest in their research, flipping the script on when, where and how LGBTQ activism got its start.

“A lot of our process is just asking the same questions over and over and over again, and getting deeper each time,” says Gossett. “We were in Indiana at the Kinsey archives and we were asking questions about cross-dressing laws and how they were playing out in the 50s before Stonewall… and then we were in LA asking the same questions again; asking people who were creating nightlife spaces or inherited spaces from the 50s [about] the overlap between anti-black racism and cross-dressing transphobia.”

There is this sense that LGBTQ activism began in a vacuum at a gay bar in New York called The Stonewall Inn. And even today, at the height of trans visibility, the media tries to paint the Stonewall riots as a white male-centric movement. This is evidenced by the recent feature film Stonewall, in which gay director Ronald Emmerich attempts to paint “the definitive story of the 1969 Stonewall Riots in New York City for a new generation.” There’s just one problem — the lead character is a fictional amalgam of influential fire-starters represented by a very white, very cis, gay male named Danny Winters (played by actor Jeremy Irvine). But anybody who has bothered to lift a finger to examine this historic moment knows that the Stonewall riots were championed by lesbians and drag queens and kings and trans women of color like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera.

Gossett and Dunham prefer not to expend their energy hollering about the ways in which the patriarchy is presented to us, but rather to create their own spaces to tell the stories that need to be heard. Not a direct response to Stonewall but certainly a healthy alternative, Gossett and her filmmaking partner, Sasha Wortzel, are currently producing a film called Happy Birthday Marsha! about Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera and their roles as trans activists before, during and after Stonewall. This version of the Stonewall Riots presents us with an intimate portrait of the two women who were truly at the center of the riots: trans women of color. And though a narrative with this lens is essential to the queer film canon, Dunham and Gossett also seek to highlight the ways in which trans and queer activism was absolutely happening before anybody had heard the words Stonewall.

“Stonewall was every single Friday when you were out there trying to be with your friends and trying to survive, and also trying to have fun, and also trying to get laid… and also trying to wear what you want to wear!”

Dunham and Gossett want us to look outside the west village and find the queers who were existing, truly existing, in other cities and towns across America in the decades before Stonewall was even a glimmer in Marsha Johnson’s sequin bustier. “Stonewall is ‘Stonewall’ — Capital-S STONEWALL — but for a lot of people Stonewall was like every night of their life,” Dunham said. “Stonewall wasn’t just like one thing. Stonewall was every single Friday when you were out there trying to be with your friends and trying to survive, and also trying to have fun, and also trying to get laid… and also trying to wear what you want to wear!” Dunham is referring to the many little movements that took place in a person’s everyday life. Something as simple as wearing a dress outside in the face of strict cross-dressing laws was a form of civil disobedience that sparked many confrontations and riots. One being the Los Angeles Cooper’s Donuts riot of 1959, ten whole years before Stonewall. Another is the 1966 Compton’s Cafeteria Riots in San Francisco. “What does it mean,” asks Dunham, “to not look for the event or the moment or the person that has the capital letter, but to look for the life that’s expansive and doing all of this work that doesn’t get remembered in the way that institutionalized histories and institutionalized success gets remembered?” Gossett and Dunham are trying to live that “expansive life.” And I would say they are succeeding.

Part of the life that’s expansive is about our human connections, the small moments of choosing whether to reach out or push away that make up the emotional network that is the LGBT community. Dunham and Gossett argue that empathy is at the heart of movement building, especially as trans and genderqueer activists in feminist and lesbian communities. “There’s also just so much biological essentialism that it’s really hard to then not take that on myself and then do it to other people, right?” Gossett is explaining the ways in which we reproduce violence onto the communities we believe are holding us back from achieving our activist goals. This includes both other oppressed minorities, as well as privileged individuals we perceive to be oppressors. “That’s why I have so much empathy… like I’m so hurt by transphobia and that’s why it’s so important for me to not assume people’s pronouns and definitely not assume their gender. People walking down the street, we can talk about in all different kinds of ways. We can talk about all the harmful things a person might have done without being like ‘that man, y’know, did this thing… That cisgender man said this to me… It’s really wonderful I think right now to leave space for everyone’s gender self-determination.” The two are really diligent about using self-reflection as a means of identifying harmful aspects of the culture within they participate. Dunham grew up in a liberal ‘supportive’ environment, but still experienced the weight of biological essentialism on her gender expression.

“I so wish that when I had been young there had been adults and mentors and worlds that had welcomed me into a way of understanding myself as queer without enacting biological essentialism onto myself,” Grace said. “I was a little kid who was told I was a girl but who intensely asserted that that’s not who I was. I was like call me Jimmy, get me a leather jacket, I want a babysitter that is on a motorcycle and has a very large beard. And because of the way I was enacting who I was, the thing I got reflected back at me is ‘oh you’re a lesbian,’ not ‘oh, this is a young person who doesn’t feel good about the role they’re being told to inhabit.”

But instead of developing resentment toward the people who assigned Grace’s gender for them, they work toward recognizing that same tendency in their self, and fighting it. “It’s easy as somebody who is consistently read as a white lesbian and as someone who came into my queer identity having a relationship to that history to feel a lot of anger at the ways in which people who came before me enacted these kinds of violence, but I think [it’s better to look] at those moments as an opportunity to think about just how deep the state goes into us and into the ways that we reproduce the state’s violence.”

Okay, so after this self-examination, what are the next steps to building trans-inclusive lesbian and feminist communities? “I think I have this moment with you again and again,” remarks Dunham to Gossett, “where we realize the work we want to do we’re already doing… There’s so much pressure to find the right thing to do, or find the right work to do or do the most impactful most ambitious thing, but chances are you’re already doing it.” Gossett couldn’t agree more.

Activism isn’t necessarily about being at the protest or at the organizing meeting, but about being in a practice. “Having a space to be in a practice where you do it in small ways every day for a while, rather than thinking that it’s outside of you and you have to do some huge thing and organize around it that way. We can do small everyday ways of being fabulous and it’s transformative. Or, small everyday ways of being in a collaboration-slash-friendship.” For example, on July 11th, Dunham and others hosted a reading and party, Summer Nights On Jupiter, at a historic Lower East Side community garden called Le Petit Versailles. The house was packed. Afterwards the stage became an open-mic where audience members were invited to sing and share their own poetry. This on its own was a simultaneous act of celebration and mourning for the pioneers of trans liberation.

“Feeling beautiful, feeling hot, feeling sexy, is getting things done.”

“How are you supposed to get things done if you don’t feel good about yourself?” Dunham proposes, while Gossett counters with, “Feeling beautiful, feeling hot, feeling sexy, is getting things done.” They are, of course, in agreement. “Feeling good is some of the hardest work that we can do,” Dunham says, “You’re not just an activist if you try to change legislation, you’re also doing amazing transformative work if you teach your friend to do her make-up. You’re also doing amazing transformative work if you find a way to go steal some dresses with one another and make sure you don’t get caught so that you have the clothes you need to be who you want to be. That’s what I’m so into right now.” That is the space Dunham and Gossett aim to create.

“It’s actually is really risky to have fun in a way you’ve been told not to… so, we’re starting to work on planning a big costume dress-up party where we’ll have lots of clothes from different decades, different periods, different themes and sets and tons of our friends and young people who maybe have gotten to experiment with the clothing that they like, and maybe haven’t… will have a safe space to go fucking wild.”

How do Dunham and Gossett manage to feel safe when they are so often concerned with making others feel safe? How do they maintain their exuberance and optimism when they are entrenched in the tragedy that appears to be the trans experience in the age of information, visibility, and media corruption? How do they protect their big and open hearts? Grace puts it in terms I can fully understand: “I feel like I really loosely use the term research to talk about what we do together, because a lot of what we do together is just be in a friendship with one another,” Dunham says, unafraid to complicate the terms of their partnership. “We’ve just been doing a lot of storytelling… this is what is sexy to us, this is what inspires us, this is what makes us feel like the world is this magic place.”

One Black Unitard, Three Badass Lady Costumes

Between the ages of seven and eleven, I wore the same store-bought witch dress for my costume every year. By the time I was eleven it was the length of a shirt on me, but I made it work… sort of. I was a witch, a zombie, a fallen angel, and the night sky. The night sky costume consisted of me painting my entire face black and drawing sloppy white stars all over my face with stage make-up. I looked more like the bubonic plague. My enthusiasm for Halloween and crafting my own costumes has not faded, but my technique has definitely improved. And thank goddess, because these days Halloween starts at ComicCon and doesn’t end until everybody has gotten over their post-Halloween Day Parade hangovers. You’ll inevitably have to go to more than one Halloween party and incidentally can’t be caught rocking the same ‘fit at each one! But crafting costumes can get expensive. So, here are four costumes you can pull together using the same basic unitard/romper thing.

ASOS Curve Exclusive Bardot Jumpsuit on sale for $33.00, ASOS Bodyfit Jumpsuit With Wrap Bardot $44.79

The first one is long-sleeved. If you live in warmer climates, maybe you want to cut the sleeves, but it’s usually cold in my neck of the woods on Halloween, so chances are I’ll be rocking a cardigan that color-coordinates with my costume some way.

When crafting multiple costumes, make-up and accessories are key. They sell the whole dang thing. For all of these looks, you’ll need:

Clockwise from left: Ben Nye Lumiere Creme Wheel $19.99, Ben Nye Lumiere Grande Wheel in Silver $10.99, Set of 4 Teardrop Beauty Make-up Blenders $7.99 — these ones are hypoallergenic.

1. Catwoman

Possibly the easiest of them all. The make-up is entirely up to you, but your upper face will be covered so there’s no need to worry about eye make-up.

Clockwise from bottom left: Balaclava Motorcycle Mask $10.87, 6-foot Braided Leather Bull Whip $9.99, Harlequin Black Eye Mask $4.89. Image via IGN.com

The costume: your jumpsuit, a balaclava over your head, party mask, cat ears. If you’re gonna buy a whip I suggest getting one you’ll actually use again (wink). You could make your own cat ears out of a headband and wire — unless you’re feeling lazy, in which case you can buy them.

2.Ursula

Mey also mentioned this as a potential witchy costume with some outfit ideas, but this version is a bit more DIY. I enjoy going wild with makeup, but if you’re looking for something low-maintenance and easy to throw on, just take some of your silver make-up and brush it along your collarbone, highlight your cheekbones, and maybe create an exaggerated widow’s peak on your forehead. Shade in some of the purple from your color wheel around the edges of your face to give it a little dimension. If you’re looking for a hardcore make-up tutorial I found a pretty incredible one here. But we laywomen want to be able to party all night without ending up with our eyebrows melted into our chins. Throw on some drugstore red lipstick, aquamarine shadow and black liquid liner. Don’t forget her signature mole on the bottom left of your lower lip. Lastly, douse your hair in white hairspray and let it go wild.

CLockwise from bottom left: Wet N Wild Lipstick in Red Velvet $4.50, Jerome Russell BWild Siberian White Color Spray $8.99, MEXI Makeup Waterproof Leapord Shell Eyeliner Pen $1.99, NYC Color Sparkle Eye Dust in Aquamarine $2.70. Image via Disney Wikia.

This next part you can either sew or just safety pin. Just get yourself three or four pairs of purple pantyhose (depending on whether you think Ursula is a squid or an octopus) and stuff ’em with cotton. Pin those mofos to your body suit and you’re off.

MUSIC LEGS Opaque Solid Tights in Black and Purple $9.00 per pack of 2, Eco-Friendly Recycled Fiberfill $10.87.

3. Morticia Addams

This one is so easy, you guys, I can’t even. Makeup consists of dusting your face ghostly pale, re-applying that same red lipstick, black liner and some smoky eye.

Top Right: Ben Nye Super White Face Powder $7.99, NYX Hot Singles Eye Shadow in Moonrock $4.50. Image via Express UK

So assuming you don’t own a black bell-sleeved shirt, how do you get those bell sleeves without purchasing a whole new dress? Make them out of pants! Just take those crazy festive bell-bottom leggings, cut the legs off and shove them on your arms. Ba-da bing, ba-da boom.

Don’t worry, Morticia ma belle, Halloween is basically an entire month long.

20 Recipes That Were Perfectly Healthy Until Bacon and Butter Came Along

Hello and welcome to this thing we’re doing where we help you figure out what you’re gonna put in your mouth this week. Some of these are recipes we’ve tried, some of these are recipes we’re looking forward to trying, all of them are fucking delicious. Tell us what you want to put in your piehole or suggest your own recipes, and we’ll talk about which things we made, which things we loved, and which things have changed us irreversibly as people. Last week, we ate figs.

So after thirteen years of vegetarianism and an abrupt realization of my digestive issues, I had to cut bread and dairy out of my life forever. In lieu of something like a log of goat cheese and a baguette for dinner, I turned back to red meat, namely bacon, and quite a lot of it. Turns out red meat isn’t so great on the stomach either, but I discovered that being a carnivore really suits me. Actually, if I pretend hard enough that butter isn’t made from milk, I can imagine that my insides aren’t turning against me. So, in honor of my inability to maintain a healthy diet, here are 20 recipes that were perfectly healthy until they were blessed by bacon and/or butter.

1.Bacon Wrapped Avocado Fries

2.Sweet Potato bites with Avocado and Bacon (Paleo and Gluten Free)

Because avocado balances out the unhealthy stuff.

3.Bacon Wrapped Bananas

Jeez can you imagine if you used sweet plantains instead? Can you imagine?

4.BLT Salad

Recently realized that if you add mayonnaise to any cold meat it automatically makes it a salad. Really complicates my whole outlook on healthy eating.

5.Bacon and Brussel Sprout Hash

This recipe was written for people following something called the KetoDiet. I dunno about all that, but this looks unbelievable.

6.Bacon Wrapped Dates with Balsamic Reduction

Classique.

7.Best Potato Salad

Is this real life?

8.Butter and Milk Boiled Corn

I want to kiss the person who invented this recipe. This is mad genius.

9.Homemade Honey Butter

Because as far as I’m concerned honey is a health food.

10.Bacon Roasted Corn

Is this taking it too far? One way to find out.

11.Bacon Jalapeño Deviled Eggs

Putting the devil in deviled eggs.

12.Cheesy Bacon Hassleback Zucchini

13.Bacon Wrapped Grilled Peaches with Balsamic Glaze

Of all the foods one could wrap in a smoky blanket of bacon, how id I not think of this before this foodie blog did?

14.Prosciutto Wrapped Asparagus

Prosciutto, bacon’s suave european cousin.

15.Strawberry Poppy Bacon Chopped Salad

16.Broccoli Salad with Bacon

Forget cheesy broccoli, bacon is the new cheddah.

17.Blackberry, Bacon and Blue Cheese Salad

When in doubt, alliterate.

18.Quinoa and Kale Salad with Avocados, Apples and Bacon

I think this is actually still genuinely good for you.

19.Spring Quinoa Salad with Honey Lemon Vinaigrette

It’s not in the title but I promise it does have bacon. And peas! I seriously adore fresh peas. So damn cute!

20.Bacon and Brown Sugar Roasted Sweet Potato Salad

Personally there is way too much cooking involved to call this a salad.

Queer New York Fashion Week: A Parade of Bold Ideas and Fresh Faces

by Hannah and Aja

Inarguably the most inclusive and supportive fashion show to come out of NYFW, VERGE: Queer New York Fashion Week at the Brooklyn Museum was a parade of fresh ideas, fresh faces, and queer community. With the stunning Beaux-Arts Court at the Brooklyn Museum as its backdrop, eight queer designers donned their queer, trans, fat, brown and disabled models in an exclusive first look at this season’s boldest, brightest, queerest and most dapper Spring/Summer collections.

Beaux-Arts Hall at the Brooklyn Museum. Photo by Hannah Hodson.

I went behind the scenes to catch the organized mayhem that breathes life into New York’s largest queer fashion week event. Backstage, models carved a nook out of the chaos to get all gussied up in designs by Sun Sun, Not Equal by Fabio Costa, KQK by Karen Quirion, LACTIC, Fony, MARKANTOINE, SAGA by Sandra Gagalo, and Jag & Co..

Models wait their turn to walk the runway for Not Equal. Photo via Fit For A Femme

There were some big names on and off the runway. Verge highlighted some of these models in a press release:

Over 70 models who challenge traditional gender constructs took center stage, including celebrity models Rain Dove (the most cast female model during the inaugural Men’s NYFW) and Ryley Rubin Pogensky (one of 17 trans-identified models in the groundbreaking Barneys New York ad campaign shot by Bruce Weber.) Melanie Gaydos, as well as Prince Harvey, the hip hop artist who secretly recorded an album at an Apple store, were just some of the many other prominent models who dominated the runway.

In attendance were singer/designer Margeaux Simms, and androgynous models Elliott Sailors and Harmony Boucher.

Ali Medina backstage before walking for KQK. photo by Hannah Hodson

Models prepare to walk for Jag and Co. Image via Fit For A Femme

Rain Dove backstage at VERGE. Photo by Hannah Hodson

But the true stars were the team behind the production, one of whom was Autostraddle Beauty Editor and Fit For A Femme blogger Aja Aguirre working the runway visuals. The people at Colette Lee Productions managed the runway and provided the hair and makeup team. Producers for the event included Van Bailey and Zahyr Lauren from bklyn boihood, Winter Mendelson and Christiane Nickel from Posture Magazine, and Dina Habib and Danik Yopp from Montreal based D.Y.D.H Productions.

Melanie walked for SAGA NYC. Photo by Katya Moorman/Karen L. Dunn

Krishna, 11, walked for Sun Sun. Image via Fit For A Femme

Aja Aguirre, Elliot Sailors and Anita Dolce Vita. Photo by Alyssa Meadows

Last and most certainly not least, Anita Dolce Vita and Dez Irani at DapperQ, the brains behind the whole operation, worked day and night to make sure the event was highly accessible (the Brooklyn Museum asks for a suggested donation but won’t turn anybody down due to lack of funds) and highly entertaining, with “How-To” stations doing cat-eye and glitter lip make-overs run by Aurora Wells and Sonam Chandna.

Anita Dolce Vita (left) and Dez Irani (right) take a bow to raucus applause after thursday night’s show. Photo by Oscar Diaz

And did you know that Ms. Dolce Vita is a full-time nurse? On top of working tirelessly to bring inclusive queer fashion to the forefront, Dolce Vita spends her days healing people. The same might be said for what DapperQ does for queer, trans and gender nonconforming folks. The ability to live authentically by wearing the clothing that feels true to your gender can be life-changing and even life saving for some folks. Dolce Vita says she uses a lot of her nursing skills to pull off fashion shows:

“Assess, triage, delegate,” she says. “Many people think that fashion shows are easy to produce. They are complete chaos behind the scenes. I utilize many of my nursing skills to make it all come together so that none of this chaos spills over on stage, whether it be coming up with a creative solution to fix a ripped garment on a model minutes before showtime, or troubleshooting glitches in a designer’s music.”

Even though VERGE was not an official IMG Fashion Week event, Dolce Vita says it was included on the CFDA calendar, and that it was crucial this show be seen as professional and as much a part of Fashion Week as any other event: “NYFW is such an staple event for our city and is one of the world’s major fashion weeks. We feel that the LGBTQ community should have a voice in, and be a part of, NYFW considering how mainstream fashion is co-opting our style but not providing space for all bodies to exist in fashion.” VERGE was a one-time collaboration between DapperQ and its producers, but DapperQ has been hosting standalone shows at places like the California Academy of Sciences and Brooklyn Museum since 2013. Last December, DapperQ presented (un)Heeled at the Brooklyn Museum to great fanfare.

Models take their final waltz after walking for the Sun Sun. Photo via Fit For A Femme.

models for LACTIC, the evenings most outlandish line, make their final rounds. Image via Fit For A Femme.

To be perfectly honest, Queer Fashion Week is the only kind of Fashion Week I want to be at; community-creating, gender-affirming, body positive, anti-racist feminist fashion week. Yes, please.

“Addicted to Fresno” Is Your Next Favorite Movie from Jamie Babbit and Natasha Lyonne

Director Jamie Babbit, who brought Natasha Lyonne down from the heavens and delivered us But I’m A Cheerleader has once again bestowed upon the lady-loving community a dark and twisted comedy: Addicted to Fresno. At once completely deranged and oddly sweet, Fresno follows two sisters in a codependent relationship in which Martha (Natasha Lyonne) habitually picks up the pieces behind recovering sex addict Shannon (Judy Greer). And in case you were wondering, yes, Lyonne plays a lesbian.

images courtesy of MPRM Entertainment

The film premiered on September 3rd at the SVA theater in New York as part of NewFest, in partnership with OutFest and the Film Society of Lincoln Center. The screening of this particular film kicked off an effort to showcase more films by queer women. While queer women are certainly represented on screen, it’s really the brains behind the whole outfit that make the film uniquely suited for this mission. Babbit’s wife, Karey Dornetto, wrote the screenplay.

Jamie Babbit (left), Karey Dornetto (center), and Natasha Lyonne (right) behind the scenes. image via MPRM Entertainment

Both Babbit and Dornetto have established themselves in the industry without pigeonholing themselves as queer artists. Babbit directed eighteen episodes of Gilmore Girls; Dornetto started out as a staff writer for South Park. It is precisely because of their diverse and varied resumes that the writing and direction of the queer relationship in this movie is just so perfectly NBD. There’s nothing sensational or special about the courtship between Martha and her wry karate instructor, Kelly (Aubrey Plaza). It’s just as awkward and confusing as any other dating-your-physical-trainer scenario might be. Okay, there is that one scene with all the lesbian softball players fondling massive purple dildos. That did happen.

image via MPRM Entertainment

Fresno is a perfect example of how women are an underappreciated and untapped source of cutting edge talent. Sure, the dick jokes abound, but I can’t remember the last time I heard a dick joke that was actually funny until I saw this movie. Given the opportunity, women can make (and are making) indie content with mainstream appeal. At the Q&A after the September 3rd screening, Jamie Babbit made certain to thank Gamechanger Films, which finances woman-directed films in an effort to close the gender gap in filmmaking. An admirable mission, and one that brought us this spunky little gem.

A murder, Fred Armisen, a bar mitzvah and Molly Shannon. What more can I say? The movie is a barrel of laughs, and the cast is chock full of comedy royalty. After what feels like a marathon of raunchy humor and aggressively casual sex, the film has some trouble tying up its loose ends, but it’s well worth the ride. You can download Addicted to Fresno on iTunes, stream or rent it on Amazon, or catch it in theaters beginning October 2nd.

Watch Beth Malone Figure Out She’s a Lesbian In Her One-Woman Show “So Far” at Joe’s Pub

Luther Ingram, Jodie Foster, Kristi McNichol, and Connie Chung all play crucial cameos in Beth Malone’s So Far, and that’s all in the first fifteen minutes. The Fun Home star returned to her roots at Joe’s Pub at the Public Theater in New York City on August 31st to perform a one-woman cabaret show following a rural lesbian through her tomboy childhood, an engagement (to a man!), her first stint as an actress in New York, another marriage (to a woman!), and her ever-tense relationship with her Colorado cowboy father.

Malone is slight in stature, but commands the stage with epic confidence, opening the act with Luther Ingram’s “If Lovin’ You Is Wrong (I Don’t Wanna Be Right)” — a song I didn’t know was so gay until Malone sang it. Her wit is biting, her story relatable, and her voice is like an angel’s. Using the storytelling aid of paper-plate puppets of Jodie Foster, Kristi McNichol and Connie Chung, we are transported through the countless childhood “aha” moments that should have led Malone to realize she was a big, fat, bleepin’ lesbian, but which only served to leave her confused into early adulthood.

photography by Kevin Yatarola

Though it takes Malone until she’s already promised to a man to finally sleep with a woman for the first time and fully realize her lesbianism, her awkward and uncertain stumble toward this conclusion is one most queer women will recognize. A smaller (though, I imagine, still quite large) contingent will relate to her tragic and estranged relationship with her right-wing, Rush Limbaugh-enthusiast father, with whom she was once inseparable.

Malone tells us about getting an on-stage kiss from Barbara Mandrell at eleven — “on the LIPS!!!” — exchanging Christmas gifts with her mother in a parking lot, and getting type-casted on the New York musical theater scene: “‘Scrappy’ is a euphemism.”

With impeccable comedic timing and an ear for the queer in almost every musical genre, Malone is able to process in one show what many people are unable to process ever in their lives. It’s a lot. So much, in fact, that we are rewarded with a short reprieve from all the feelings with a mid-show interactive theatrical break called “Ask a Lesbian a Question,” during which Malone and Fun Home book writer Lisa Kron answer the audience’s most pressing questions as can only two very sarcastic lesbians can. When asked by a gay man about lesbian “labels,” Kron says she self-identifies as a “femme, top, coupon-cutting, childless MILF.”

Lisa Kron and Beth Malone argue over whose cats are the cutest photography by Kevin Yatarola

So Far was written by Beth Malone and Patricia Cotter. Musical direction is by Susan Drausstrong and directed by Peter Schneider. The show is produced by LezCab, whose mission is to “create an accurate and meaningful representation of queer women in order to foster equality and community.” They accomplish this task through the magic of theater. They also host social networking events for queer women in the theater, which can be found on their events page.

Melancholia In The Sunshine

feature image via shutterstock.com

I’m trying to build a metaphor around a patch of dirt I like to call a backyard. My boyfriend has this little area behind his house. After two years of watching the neighborhood use it for an illegal dumping ground, we decided to make something out of it. We emptied some left-behind planters of sulfuric sludge, cleared away cinderblocks and an insulating layer of cigarette butts and started to make something green from something grey. We dragged some trash out, dragged some back in (like two grills that lean precariously on a leg and a wheel). We set out a card table, turned over some leftover lumber onto some leftover paint buckets to make benches — y’know, really classed the joint up.

We’re trying to plant wildflowers amongst the weeds, but this soil is rubble.

I’m sitting here with a nice cold cider and my laptop. There isn’t a cloud in the sky. I should be happy — ecstatic even — but there is a distinct sense of melancholia that shrouds me. This happens every summer, and what makes it worse is that I can never identify from whence it comes.

I am, for all intents and purposes, a very happy person. I enjoy all manner of privileges and good things, some of which I worked very hard to achieve, and many others I happened upon by chance. I have two jobs I love very much, and which allow me to express myself creatively without much censorship. I do not suffer from clinical depression as far as I know, though it does run in the family. What I’m saying is, I guess, I got life.

It didn’t seem so hard when we first started, but tending to damaged roots is a slow and delicate process they want us to handle with care.

Don’t you ever want to take a sledgehammer to the whole damn place? Douse it in kerosene and watch it fucking burn? I like to think a tree might rise from those ashes; it probably isn’t a risk worth taking.

I like to blame my morose tendencies on the weather. In the winter, it is easy to say you’re just not feeling well because it’s fucking frigid and who can be happy under those conditions? But that kind of sadness has a name: seasonal depression. You’re sad because it sucks out. You’re sad because you can’t see the people you love as often because it sucks out. You’re sad because you can’t go running around in your skivvies because it sucks out. You’re sad because you haven’t seen a tree that doesn’t look like it wants to commit suicide since September. It isn’t until the summer, when the frost melts and the icee man comes calling and the pool is open and the yard (however ridden with stubborn weeds) starts to incubate natural life, that you realize the source of your woes isn’t dependent on the weather. It’s you. Or it’s me. I don’t mean to project.

So we excavate this rubble that cannot and will not give life. You find a dead rat while you’re raking the yard and you pretend to throw it at me. I yell at you because that is so incredibly disgusting. And you look at me like you didn’t know I would get so upset about something so small. But I am, and here we are, in this yard full of weeds.

I’ve been in a relationship with a man for over three years now, which is at least three years longer than any other relationship with any other person, male, female or otherwise that I have ever sustained. This is the Big One. I have always been the reason something goes wrong. I become restless, or anxious, or needy, or just batshit crazy. And it always seems to happen about right now, when the weeds start to show green in his little patch of dirt.

Last summer, I told him I wanted to see other people. Specifically, that I wanted to start seeing women, that this was a huge part of who I am, and that maybe non-monogamy was equally a part of who I am. So, we took a little break. I will be the first to admit that it was a selfish albeit necessary move for the both of us.

Past relationships have always been a product of convenience, emotionally or geographically or both. They ran their course and didn’t need much help because once they were over there was no question as to whether they would ever return. But, because it seems plausible that this boy might be the person with whom I spend the rest of my life, I have to start counting my blessings; I have to start planting seeds, the kind that will grow back next year and the year after that. Our little break was one kind of seed. Our open relationship is another. I’m hoping that that the way I manifest happiness in my life is by creating new things with my friends, lovers, and family.

We’ll have to take it slow I guess. Pull some weeds. Lay some soil. In the meantime we’ve got this tomato plant we’re growing in a big fat plastic pot, painted the color of terra cotta, that we found beneath some cinderblocks that smelled like piss. And for now we’re gonna stick it right in the sun. Already the leaves smell spicy and green. There is a little promise of something plump and red. I’ll try to nurture something that tastes and smells and looks as fine as you do.

A garden needs constant tending. It needs biodiversity. Those things can be hard to find in a city like New York. It seems as though everything you try to grow is vulnerable to elements out of your control: flash floods, vermin, alley cats. The summer heat brings every threat to the surface. So you trim and weed and build trellises and cages. And still one day you wake up, and a rat has burrowed a hole in your basil plants.

Much like a garden, a relationship needs tending, especially one vulnerable to predators. So when you show up at your boyfriend’s house at 4 am because you can’t sleep, creep through the 1×1 hole in the basement wall, hoping to tuck yourself under him arms so that he will wake up wrapped up in you, only to find that he has spent the night in Taylor’s bed, it’s important to remind yourself that you are not despairing because you are unloved, just temporarily lonely. True love manifest itself in tinier, more complex ways — like the look on his face when he comes home later that day, and sees you’ve been waiting for him, naked and drooling on the pillow and he assures you that you are his number one priority and he should have told you he wouldn’t be home last night. There is a feeling when you learn a new thing about yourself and the person you love; the feeling that you have built something solid. This is what staves off the sadness.

I had this dream we woke up at dawn, and the morning glories had wound themselves around the whole yard. They spun around barbed wire fence toppers and made a bed of themselves down the whole block, creeped through the doorways of the Louis Armstrong Projects and made everything smell so… crisp. They circled the elbows of your other lover’s freckled arms. They pulled at the orange red tendrils of my own. And nobody was awake to see it but you, me and the sparrows.

Building a relationship does not preclude exploring others. Learning what you love and hate about the bodies and behaviors of other people writes an encyclopedia of human nature that helps you understand how you can manage to love the sum of one human’s parts more than any individual part of any other person you have ever known. There’s no formula for this. Feelings will be hurt. Mysterious tiny animals will eat your tomatoes. It will feel like a crazy, impossible, futile thing to do. But, when September rolls around and you know you both put in good, hard work instead of letting the melancholia creep its way inside of you you, the impending task of staying warm in the winter doesn’t seem so daunting.

This is the first summer of my adult life that I have not tried to leave a relationship; the first time I feel like I have the tools to tend a garden.

This Shit Rules: Damage Control

“This Shit Rules” is a beauty column where staff people list the items they can’t live without – the makeup, beauty products, and other shit we use every morning, before we go to bed, or in the car on the way to work.

Once every few years, I get tired of dealing with my curls. A little blow-out can give me a break from the fussing and futzing with out-of-place corkscrews or lopsided bed-head. So I took a little trip to my local Dominican salon to get a wash n’ blow. Now, I’m normally very, very, very particular about what I put in my hair, but I’ve had my hair blown out at this Dominican salon before, and I figured one little shampoo and condition with Suave or whatever they use couldn’t hurt. Whoo boy was I wrong. When the lady was done wrapping up my newly straightened locks I could not believe how incredibly straight she got it to look. Nobody has ever gotten my hair to be so damn straight and silky. It wasn’t until all of my hair was falling out in the shower a week later that I realized something had gone horribly awry.

A hairstylist friend informed me that they must have put a keratin treatment in the conditioner, which, when used with heat, bonds to the hair and basically murders it. Looks great straight, looks like straw when you wash it out. I was mortified. I immediately ran to Ricky’s to stock up on every organic deep conditioning treatment they had on the shelves. In the name of protecting your hair from damage and your pockets from the exorbitant sums of cash I spent trying to find the perfect product, here are the four that actually worked. All of the products listed here are free from parabens and sulfates, which are apparently very bad for curly hair or at least my stylist says so and that’s good enough for me.

Carol’s Daughter Monoi Oil Repairing Conditioner

I really couldn’t tell you what monoi oil is, but I like to imagine it is suckled from the nipples of woodland nymphs, because more than anything else I used, this conditioner got my hair feeling better than normal right quick. They also make a deep conditioner and a leave-in solution, but given how effective just this one product is, and the steep cost, I’d say skip the other stuff. And? It smells like dewdrops and rainbows.

image via Curlmart

DevaCurl Heaven in Hair

I never realized how much this shit rules until I really needed it. If you’re dealing with really terrible damage and need some extra help taming your rats nest, I wholeheartedly endorse this product. All of the Deva products are high quality, but they are also mega expensive (as are most products marketed toward curly-haired and “ethnic” women, but that’s another article for another time). Get a small 8oz. tub for occasional emergencies and try not to break it out unless you really need it.

image via Ulta

Shea Moisture Curl Enhancing Smoothie

Once you’re out of the shower and you’ve glooped your hair full of enough moisturizers to re-hydrate the state of California, you can squeeze the water out of your hair and run some of this stuff through it. Of all the leave-ins in all the land, this is the least “crunchy,” meaning that when your hair dries it won’t feel like it’s encased in a layer of ice. The coconut hibiscus smell is a little too saccharine for my taste but it doesn’t stop me from using this product every. single. day.

image via Amazon

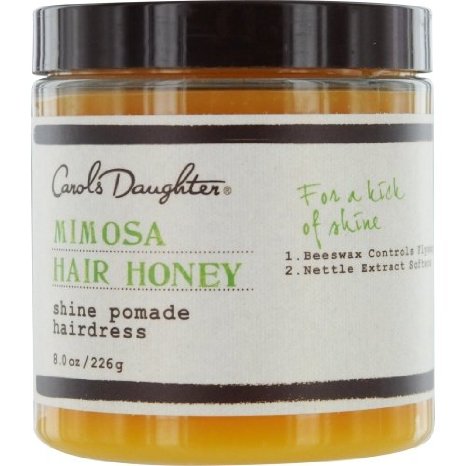

Carol’s Daughter Mimosa Hair Honey

This one isn’t for everybody. It smells so amazing you might be tempted to dump the whole canister on your head but BEWARE! It scoops out like a pomade, but then sort of melts onto your hair as it dries. It is very very oily. I recommend it only to smooth frizz and add a little extra shine on days when your hair is feeling extra dry or damaged. Try to keep it away from your hairline. Also you may find yourself trailed by a rabble of bees. This has literally happened to me a lot of times and I honestly don’t know what to do about it.

image via Amazon

Party of Five: Nikki Levy of “Don’t Tell My Mother!”

Party of Five is a quick little ditty where we ask someone (anyone we want) five questions (any five questions we want) and they answer them. This doesn’t have to be necessarily ‘queer’ — it doesn’t have to be anything at all, except five questions and five answers.

Nikki Levy is a Los Angeles-based lesbian and film executive who developed the brilliant and heartachingly funny storytelling series Don’t Tell My Mother! The show (which, duh, is available as a podcast) features actors, stand-ups, and performers such as Tracee Ellis Ross, Fortune Feimster, and Kate McKinnon (the list goes on), telling stories they would never want their mother to hear. Though not explicitly a queer performance, many of the stories are super gay. As queer storytellers ourselves, we jumped at the opportunity to pick Levy’s brain before her next performance in Los Angeles on March 26th.

Nikki Levy, courtesy of Nikki Levy

What inspired you to start doing this podcast?

Nikki Levy: I’ve been a development executive in Hollywood for a long time. What that means is that I develop movie ideas with writers based on pitches, books, scripts, plays, etc. As an exec, I’m supposed to be “the suit” in the room working with “the artist.” Though I look pretty fabulous in a suit (see exhibit A, ladies), I am not one! Oh my G-D, I am so not.

I’m a Jew from New York with an eccentric scientist mother, I’ve never been one to follow the rules. As a matter if fact, I’ve been told my entire life by bosses, teachers and camp counselors that I needed to “settle down.” They said I was “too much,” “too loud,” “too inappropriate.” The idea being that I should keep it small – you know “less is more.”

So I tried that, specifically at work: to be quieter, more reserved, less obtrusive. But that meant I was less of myself. And that felt more awful than being told I was too much. As my teacher Alexandra Billings (who plays Davina in Transparent) says, “Less is not more. Less is always less.” And you know what, I didn’t want to be less.

If I was too much for certain places, I was going to create a place where it was wonderful to be exactly me. And for you to be 100% you – weird, honest, joyful, strange, excited, vulnerable and real. All the time.

I started the Don’t Tell My Mother! show and podcast as a place where we could relish in our collective dysfunction.

Which story, so far, has been your favorite?

There are tons of stories I like, but my favorite is told by one of the best standup comics in the business – Jen Kober, a lesbian from Louisiana. Jen came to me through her manager, Justin Silvera, when we first started the show. She told the most amazing story of being a fat kid with a penchant for American cheese. Jen’s mama didn’t want her to be so fat, so she started rationing Jen’s American cheese intake. Jen didn’t like that, so she concocted a plan to steal the entire brick of Costco American cheese that her mother bought, thereby convincing her mother that she didn’t buy the cheese in the first place. What ensues is utter dysfunctional brilliance of a girl who stops at nothing for her cheese. Take a listen. You will love it! As a side note, Jen got signed by an agent from her first performance at DTMM! back in 2012. She’s doing great things now.

How long do you spend workshopping the stories before they are performed?

Something that makes this show a little different is that I work with performers on their stories. It is, hands down, my favorite part of the process. I pick people who know how to deliver material because they can make a story about eating a Big Mac sound incredible. And then we get to work. We do phone calls where we vet a few ideas for stories, and then we get under one. I ask tons of questions and help them elaborate on the details. We work together for about two weeks, going back and forth with drafts, honing the story and mining the comedy. Much of what we discuss never makes it to the stage, either because it’s too sensitive or confidential, or isn’t germane to the story.

Someone once called it “creative therapy.” I guess all my years of regular therapy paid off. Thanks, mom!

Some of my favorite people to work with are standup comics because they know how to bring the funny – no matter what the subject. The fun is allowing them to expand the story and not simply set up and pay off jokes. As opposed to standup comedy, we get to have moments of humor and emotion. A good story has both.

The show is pretty gay. Is that deliberate or are the gays just more comfortable “coming out,” so to speak?

That’s a great question. I actually did an Op-Ed for Advocate about this. As LGBT people, we’ve had to come out of the closet at one point or another. The best stories are all about overcoming struggle – they can be huge like revealing your sexuality, or small like figuring out how to get your American cheese fix. Point is, we had a goal, we fought for it, we emerged victorious (or with a prize different from but better than we could have ever imagined). As LGBT people, we are natural born storytellers. We’ve also spent so much time observing that we often pay close attention to details.

As a side note, I find that women are better storytellers than men. In my experience, men often have a hard time being vulnerable and funny. And that’s the sweet spot of the show. The women I work with have an easier time accessing their honesty. And honesty is why we’re there.

As a lesbian, I can tell you that there aren’t a lot of lesbian events happening around LA. While this isn’t a gay show per se, I always open the night with a personal story that usually involves something gay and Jewish. Can’t help it. I think lesbians like to see other lesbians share their truths, so the dykes come in droves.

Feeling “weird” or “other” is a common LGBT experience, so I think we are naturally drawn to this kind of entertainment.

Also, we’re doing a trans show in LA on June 11. Yee hah!

Nikki Levy, Geena Davis, Alysia Reiner et al. Gal Pal-ing around at a Ladies in Comedy Event in Los Angeles.

New York vs. LA: which has the better queer women’s scene?

This is a great question. I’m from NYC originally – Queens born and raised, and then moved to Park Slope, Brooklyn after college in 1999 (don’t do the math). When I lived in NYC, the girl queer scene was so… gay. I would go to Meow Mix and Henrietta Hudson ready to make some memories, and the women wouldn’t give me the time of day. Though I tried my best by wearing my Doc Martens and getting a really short, mistake of a buzz cut, I am very girly and no one thought I was a lesbian. I have big boobs, I don’t believe in baggy jeans for date night. Sue me. I also carry a purse, and I don’t own a wallet chain. Being a femme back then, no one thought I was gay. I sported a Pride necklace (the black cord with the rainbow rings) so people would have some idea. They just thought I liked rainbows.

The queer women’s scene in NYC at the time (I moved out to LA in 2002) was butch. And I never, ever fit in.

Now, cut to LA. I don’t know if it was because of the L Word, but LA was a femme for femme town. I’d walk into bars and be shocked to find out a woman is gay. She’d have on tight pants, a cute tank top, high heels. That’s the style here. And I fit right in. I joke that even the Dykes on Bikes in LA get their eyebrows done. There are no lesbian bars in LA, which is fine by me since large groups of lesbians have and always will intimidate me, but it doesn’t really matter because they’re coming out of the woodwork – literally. New York might have also femmed out since I left over 10 years ago), but LA is definitely the place for girly girls who like girls.

![DTMMmarch2015flyer[1]](https://develop.autostraddle.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/DTMMmarch2015flyer1.jpg?resize=435%2C640)

You can buy tickets for the March 26th performance featuring Jen Kober (The Middle), Angela V. Shelton (Hulu’s Quickdraw), Hannah Friedman (About a Boy), Alysia Reiner (Orange is the New Black) and Nikki Levy HERE

3 Alternative Natural Hair Looks For Scissor-Shy Curly Queers

I love my long natural hair. It is part of my heritage, my identity, and even my career as a performer. Some days, I wish I had an alternative look that might express my queerdo feels, but there’s no way I’m going to cut it all off (again). Natural hair doesn’t really lend itself to versatility, not easily at least. I rock what natural hair connoisseurs call a “wash’n’go” which sounds super simple and easy breezy but actually entails about 30 minutes of conditioning, detangling, and finger curling to smooth out the wily bits. Not to mention the approximately 20 minutes of blow-drying, which only does half the job. I spend the rest of the day with a slowly expanding afro. It is dry by maybe 4 pm. I’m really not kidding. It ain’t easy being natural, but it feels good. It feels healthy and like a part of who I am. I follow a few natural hair bloggers that make more complex natural hairdos look so easy, but I’m skeptical about the ability of the layperson who wants to achieve these looks. Given that doing my hair can be such a chore anyways, I decided to give a few of these styles a shot, and rate them based on ease, time, and queerdo suitability (1 being the easiest, quickest and milquetoast-iest, 5 being the hardest, most time consuming and gayest, respectively).

Janelle Pompadour

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s0pP3VHJLgA

I actually did this one for Halloween one year, and I can definitively say that it is easier the second time around. Make sure you do it with dry hair; it’s even easier because even if your curls aren’t at their perkiest, you can disguise them within the pouf, so it’s a good “day 3” hairstyle (hair that hasn’t been washed for three days). But it ain’t for the faint of heart. I’m going to need a few lessons in sass before I have the self-confidence to rock this one outside of the house. Ease: 2, Time: 1, Gayness: 5.

Uncanny, n’est pas?

Janelle via Mark Abraham Photography

Fro-Hawk

You get the idea.

This one is normally super easy if you start out with freshly washed hair, but I wanted my hawk to be more floppy, if you know what I mean. So I spent 24 hours with my hair in bantu knots (little knobby twists all over my head), disguised under a sweet head wrap. Those were fun to unravel, and then I just pinned up both sides into the center. Make sure to pin the sides as close together as possible, to achieve maximum height in the hair, otherwise it will be too wide and your head will look boxy. Ease: 5, Time: 5, Gayness: 5.

worth it just to unravel those little hair doodles.

Top Knot Bun With a Twist

It’s supposed to be easy enough, but I just ended up with what looked like a fresh pile of poop on top of my head. This might be a better style for people with longer hair and tighter curls so it’s easier to achieve the volume. Anyways I’m not even gonna post a picture ’cause I looked that bad y’all. Ease: 1, Time: 1, Gayness: 1.

Next time I’m gonna lock myself in my bathroom for an entire day and do temporary yarn dreads. Stay tuned.

Cathy & Marcy Celebrate Diverse Families with ‘Dancin’ in the Kitchen’

Grammy Award winning children’s musicians Cathy Fink and Marcy Marxer release their 44th album today, titled Dancin’ In The Kitchen: Songs For All Families. The recently married couple, who refer to their relationship as the “30-year engagement,” hope their album follows in the footsteps of Marlo Thomas, famous for creating the universally famous 1972 album celebrating diversity, Free To Be… You and Me. Surely you’ve heard it, maybe even suffered through assembly-time renditions in grade school. My middle school even printed Free To Be themed day planners. Thing is, though revolutionary for its time, Free To Be is a little dated. Fink and Marxer hope they can bring the spirit to contemporary issues.

image courtesy of Cathy & Marcy

Fink and Marxer want to expand our definition of diversity. They have songs about adoption (“Happy Adoption Day“) and LGBT families (Dancin’ In The Kitchen With Mama and Mommy/Dancin’ In The Kitchen With Daddy and Papa). Primarily, the duo are concerned with complicating the notion of the nuclear family, and instilling children with the notion that every family looks different. “Marlo Thomas defined a family as a feeling of belonging,” Fink tells me:

I totally love that because that includes every family. It includes every family with an adopted kid, with a foster kid, it includes blended families, it includes multiracial families, it includes single parent families… Now, thanks to the work of so many great organizations, we live in a world where when you say the word ‘family,’ you aren’t thinking of the Cleaver family anymore… you’re not thinking of a nuclear family with a white mom and white dad and 2.3 children… every family is unique.

In the song “Soccer Shoes,” a child can’t find their soccer shoes because he lives with separated or divorced parents. “Twins” is a song about identical twins, written and performed by actual identical twins. The album boasts multiple songs with titles like “I Belong to A Family” and “Family Song,” all celebrating the different ways to define family.

Fink and Marxer use this album to open up discussions about themes that many parents might be hesitant to tackle. The album contains a story written and told by storyteller Andy Offutt Irwin, “Who’s In Charge of Naming the Colors?” during which we are prompted to discuss the oversimplified ways we identify skin color. A little boy sees some paint swatches at the hardware store, and uses them to name the colors of his multiracial family. Creating space for difficult conversations between parents and children has been both a goal and a side effect of their music making through the years. In 1992, the duo invited a children’s chorus to perform on their song “Everything Possible,” written by Fred Durst. However, upon reading some of the lyrics, many parents decided to pull their children out of the project. The offending lyrics?

There are girls who grow up strong and bold/There are boys quiet and kind/ Some place on ahead, some follow behind/ Some go on their own way and time/ Some women love women/ Some men love men/ Some raise children, some never do/ You can dream all the day never reaching the end of everything possible for you.

In the end, no matter the parent’s decision, each parent had to sit down with their child and explain exactly why they were not being allowed to participate in the chorus with their friends. I asked Fink if any of the parents ended up changing their minds about participating after a conversation with their child:

There was a family who came into the studio, they had a son in the sixth grade. The father was in the military, and apparently the mother and father had some pretty ‘hearty discussions’. He was against it, she was for it and in the end they left it up to the child. And the child said ‘I definitely want to sing that song.’ The interesting discussion between the mom and dad was that they had a son in college. And the mother finally looked at the dad and said ‘Are you trying to tell me that if our son comes home from college and says he’s gay, you’re not gonna love him?’

“Everything Possible” is also included on the tracklist for Dancin’ In The Kitchen.

The newlyweds will certainly be continuing to make music that embraces diversity, and you can keep up with their albums and children’s concerts at their website, cathymarcy.com. Buy Dancin’ in the Kitchen: Songs for All Families on Amazon.

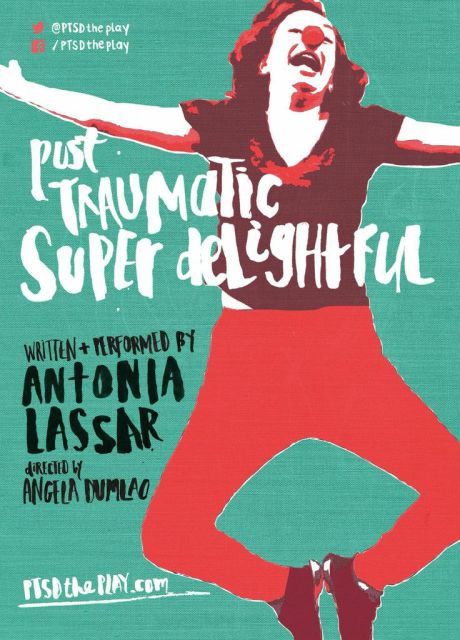

“Post Traumatic Super Delightful” Uses Laughter To Talk About Campus Sexual Assault

This past Saturday I had the rare and special opportunity to see a play called Post Traumatic Super Delightful [PTSD]. Rare, because there are only two performances left to be seen in NYC, but it was special for a number of reasons. PTSD is a one-woman show that uses humor to traverse the complex and frightening terrain of sexual violence on college campuses. Using a silent clown narrator to break the silence around personal and community trauma, playwright/performer Antonia Lassar tells the story of a campus sexual assault through the voices of a professor, Title IX coordinator, and a perpetrator. Though the performance itself tells a singular narrative, Lassar explains that the characters are actually an amalgam of stories she collected through extensive interviews with victims, perpetrators and faculty who have dealt with campus sexual assault.

Antonia Lassar, playwright/performer and Angela Dumlao, director. images courtesy of PTSD