How To Write A Spell Against White Supremacy

This piece was originally published on 10/9/2017.

George Floyd was murdered on May 25, 2020, and we stand in unequivocal support of the protests and uprisings that have swept the US since that day, and against the unconscionable violence of the police and US state. We can’t continue with business as usual. We will be celebrating Pride as an uprising. This month, Autostraddle is focusing on content related to this struggle, the fight against white supremacy and the fight for Black lives and Black futures. Instead, we’re publishing and re-highlighting work by and for Black queer and trans folks speaking to their experiences living under white supremacy and the carceral state, and work calling white people to material action.

Author’s Note (06/19/20): Since writing this story three years ago, I’ve acquired more reverence for my family’s Southern Black Baptist traditions—because at least they’re ours. We’ve retained them despite oppression and white supremacy. They’ve sustained us thus far. The Black Church is an undeniable part of my culture. So, nowadays, I’m most interested in syncretizing elements from the Black Church and my witchy spirituality. I’m not returning to Christianity, but rather borrowing aspects of my family’s religious practices that feel good and right to me. Still, my steps to writing a spell against white supremacy apply, especially in these tumultuous times. I hope you glean something from them.

Magic is rarely portrayed as a wholly positive thing. Even the lovable witches in my childhood favorite Hocus Pocus sucked the life out of kids to preserve their youthful looks. Witches, from Tituba of the Salem witch trials to the Wicked Witch of the West, are generally maligned as evil women who need to be destroyed or controlled.

Although magic’s viewed as the immoral sister of religion, both have rich histories in historically oppressed communities. We turn to them for healing and miracles, but there are some key differences between the two. Most religions require worship of a patriarchal figure who punishes you for doing wrong, while magic allows us to harness our power within. Religion, prayer specifically, has been offered as a solution to Donald Trump’s nightmare presidency and white supremacist terrorism, but what if we looked to the power of magic instead?

I define magic as creating desired change by performing rituals for those who guide and protect you, whether they be ancestors, goddesses or a natural wonder.

My altar

Magic is easier for me to digest than the Southern Black Baptist tradition that raised me. This tradition taught me to depend on cisgender heterosexual men to guide my spirituality. It taught me to be ashamed of things that I find pleasurable. When I think about the Black Church, I can’t help but think of white slave masters pacifying “savage” enslaved Black folks with the lessons of Christianity. I often feel nostalgic about the Black Church, and I honor its participation in social justice movements. However, I don’t feel welcome there anymore as a genderqueer feminist since most Black churches adhere to gender roles that disempower women and LGBTQ+ people.

Alternatively, the word “magic” fills my head with images of enslaved Black people preserving their ancestral deities in the Americas by practicing Voodoo and Santería. Magic is an ancestral practice that transcends time and oceans. To me, magic means resilience and connecting to ancestors who survived the tragedy of the Middle Passage. Magic runs through my veins and feels like my birthright. It’s stronger than white supremacy will ever be.

White supremacy forces us to draw our strength from anti-Blackness, heterosexism and patriarchy. I use magic in my everyday life to combat individual and systemic oppression. Being a writer, it’s no surprise my favorite magical practice is writing spells. I write spells to manifest positive things in my own life and the lives of my beloveds. I write spells for the healing and liberation of my communities. The first thing I do when writing a spell is find out what’s happening in the sky. Sometimes the planets are aligned just right to cast an effective spell. Major celestial events such as lunar eclipses amplify the potency of our magic.

Then, I decide who to direct my spell towards. I choose the ancestors or spirit guides who have the power to give me what I need. I’m always adding new names to this roster. Lately, I’ve been learning about Obatala, a West African orisha (saint) who is said to have created humans. I feel a kinship with this androgynous orisha who completely disregards gender and protects disabled people. I see myself in Obatala’s image, and I feel held by them as someone living with disabilities. I hope to incorporate Obatala into more of my spells in the future.

Someone else I honor during spells is Nyabingi, a Rwandese/Ugandan woman warrior who fought fiercely against European colonizers in the early 1900s. My Rwandese partner introduced me to Nyabingi, who’s now a possibility model for the both of us.

My grandmother, an OG witch.

When performing spells together, my partner and I also invoke our late grandmothers. My maternal grandmother Carolyn was a devout Christian, but how she lived her life was magic. Grandma was a compassionate lady whose many gifts were stifled by Jim Crow and patriarchy. She accepted everyone for who they were, grew thriving plants despite living in a small apartment and whipped up soul food that tasted like love feels. Wherever she is, my grandma is shaking her head at Trump. I see her face every time I stand at my personal altar, adorned with photos (including hers), trinkets from friends and family and art made by queer and trans people of color. This is where I cast my spells.

While casting spells, I channel the strength that allowed my grandma to survive during an era when Black women were disenfranchised at every turn. The words in my spells are less important than the intention behind them. My spells are straightforward, stating exactly what I want to manifest and calling on the power of spirit to make it happen. Spell-writing is my time for reflection, meditation and gratitude. I cherish my ritual of casting spells at my altar alone, with my partner and other loved ones. I’m hungry for more opportunities to do magic in community.

What would it look like for Black, Brown, trans and queer folks to include magic in our resistance against white supremacy? I’m hoping that we can begin reclaiming magic and redefining it for ourselves.

Trans Women of Color Organizers Are Building a Movement to Decriminalize Sex Work in D.C.

Feature Image credit to Darrow Montgomery

Imagine you’ve grinded for years as a member of a community coalition to get a hearing for a historic bill that will drastically improve your life if passed. A hearing is finally granted, and when the big day arrives, you scramble to get your John Hancock at the top of the list to give testimony.

Once the hearing begins, hours go by without your name being called. Although you signed up before them, representatives of organizations from other parts of the country and from other countries get their time at the mic before you. Worse, their speeches are denouncing the bill that you and other local grassroots organizers have put your blood, sweat, and tears into, labeling it harmful instead of helpful.

This was Tamika Spellman’s fate at an Oct. 17 city council hearing for the Reducing Criminalization to Promote Community Safety and Health Amendment Act of 2019, which calls for D.C. to fully decriminalize consensual sex work between adults. She said that organizations based outside of D.C. were given precedence to testify over local members of the Sex Worker Advocates Coalition (SWAC), a collection of mostly grassroots Black and Brown transgender and queer-led groups that’ve been moving in coordination to decriminalize sex work in D.C. since October 2016.

“A lot of the groups that worked with this movement were put at the trailing end of the hearing, and it was a 14-hour-plus hearing. Those voices should have been heard well ahead of them, and if anything, those that were from out-of-state should have been put at the end. Accommodating them because they’re from out-of-state made absolutely no sense to a movement that is local,” Spellman told me.

Spellman is the advocacy associate at HIPS, a D.C. nonprofit that provides harm reduction services, advocacy, and community engagement to sex workers and drug users. HIPS is the birthplace of SWAC, the DECRIMNOW campaign, and the Community Safety and Health Amendment Acts of 2017 and 2019.

When the 2017 version of the bill, co-introduced by two city council members, failed to receive a hearing, SWAC wasn’t deterred from their mission. More fired up than ever, the coalition intensified their advocacy, including appealing to city council, canvassing door-to-door and on the streets, writing op-eds, talking to the media, doing speaking engagements, and meeting with neighborhood boards and commissions. They also reworked the language in the bill to make it clear that it doesn’t endorse coercion, exploitation, or human trafficking.

SWAC’s endless hours of footwork on behalf of the Community Safety and Health Amendment Act weren’t in vain: Four council members reintroduced the bill in 2019, another council member co-sponsored it, and a hearing was scheduled. Emmelia Talarico, the organizing director of SWAC member No Justice No Pride DC, works closely with Spellman and told me that earning supporters and getting a hearing for the bill was truly a collective, long-term endeavor.

“I think all the different groups showed up in different ways. A lot of us have been organizing together for a number of years, and we have these relationships developed and this level of trust developed. We also respect a diversity of tactics,” Talarico said.

During the hard-won council hearing, Talarico, a mixed-race white and Puerto Rican non-binary trans woman sex worker, and Spellman, a Black trans woman sex worker, sat through testimony after testimony of individuals conflating sex work with sex trafficking, stating misinformation (i.e., the bill would allow for brothels and empower pimps), and even equating the full decriminalization of sex work to human chattel slavery in the US, which Spellman found particularly upsetting as a descendant of enslaved Africans.

Many of the bill’s opponents advocated for partial decriminalization, known as the “Nordic model,” the “Equality model,” or the “End Demand model,” which purports to only criminalize buyers, but both Talarico and Spellman call this a false solution.

“Studies have shown that is has not helped with trafficking, that it’s been more or equal harm to full criminalization, and sex workers are losing money. They’re losing their ability to negotiate. STDs are rising because you don’t have the ability to negotiate for safer sex, and crime is expanding because you’re not in control of where you’re meeting,” Spellman said.

While the concerns of outsiders ultimately convinced the council to not bring the bill to a vote for now, several national and international organizations are following SWAC’s lead, such as Amnesty International, the World Health Organization, and the National Center for Lesbian Rights (NCLR).

Tyrone Hanley, a senior policy counsel at NCLR, says that supporting SWAC and the DECRIMNOW campaign in reaching out to D.C.’s LGBTQ+ residents and testifying at the hearing are some of the highlights of his career thus far.

“I think what was really powerful about that day was that it was very clear that the side supporting the decriminalization of sex work was very local, very grassroots, and very community-centered,” Hanley said.

As a gay Black man, Hanley believes decriminalizing sex work is necessary to ending violence against LGBTQ+ people, but he says it’s just one of many issues that needs to be addressed to ensure trans women of color in D.C. are able to survive and thrive.

Statistics underscore Hanley’s sentiment despite the district’s progressive, trans-inclusive anti-discrimination laws. According to the Washington, DC Trans Needs Assessment Report, 57% of trans people of color in the city earn less than $10,000 a year, 49% have been denied a job due to being perceived as trans, and 21% have been sexually or physically assaulted in the workplace. Furthermore, 47% of Black trans respondents and 47% of Latinx trans respondents reported currently working in the grey and underground economy, which includes sex work.

Trans women of color are overrepresented in all of these categories but are also some of the fiercest fighters against the myriad injustices trans people experience in D.C. At HIPS, Spellman is working to end unjust evictions and excessive application fees. Talarico helped found the NJNP Collective, which provides resources such as housing, job seeker services, and jail and legal support to the city’s trans communities. The collective also offers paid organizer training to trans people of color as an alternative form of employment to sex work, which prepares them to represent themselves at decision-making tables.

Unsurprisingly, Spellman doesn’t plan on leaving decision-makers alone anytime soon when it comes to passing the bill to fully decriminalize sex work in D.C.

“We’re going to be all up their butts until we get a vote. We’re going to continue the work that we’ve been doing. We’re going to continue growing this movement. This is nothing but another hurdle that we’re going to leap over because a year ago, they did not think we would get as far as we did. They were shocked that it moved as much as it did,” Spellman said. “So now that we know we have the attention, we’re going to continue to play on that. We’re going to continue to push hard. The efforts that we put in… that’s nothing compared to what we’re getting ready to do now.”⚡

Edited by Carmen

![]()

Georgia’s Abortion Ban Can’t Be Defeated Without Queer and Trans Black Women and Femmes

Residents of liberal coastal cities have an awful lot of negative things to say about the South. I especially get frustrated when wealthy, cisgender heterosexual white people are the culprits of this sort of paternalistic talk. These folks don’t have a clue about what the South is really like.

So imagine my annoyance upon seeing that newly minted “A-list activist” Alyssa Milano and several other celebrities threatened to boycott film production in Georgia in response to recently signed bill HB 481, which will criminalize almost all abortions in the state after a pregnant person reaches six weeks and take effect on January 1.

Milano represents a large swath of cishet white women who believe that whatever meets their needs will automatically meet everybody else’s needs, a falsehood fueled by their perception of themselves as the default. Without knowing the long history of struggle against reproductive oppressions in Georgia, outsiders like Milano assume they know what’s best for my state.

Following the leadership of those who’ve never been on the ground in Georgia fighting against reproductive injustices is a losing strategy for defeating our abortion ban. Doing so erases decades of movement-building led by Black women and femmes, who despite being among the most impacted by reproductive attacks, are often overlooked when we discuss abortion restrictions.

What Milano and other celebrities should know about Georgia is that we’re the home of several Black women and femme-led grassroots organizations that approach abortion restrictions and other reproductive issues through a reproductive justice lens. These are the people we need to be taking our cues from if we hope to halt HB 481.

Agbo is the Lead Community Organizer at one of these organizations, SPARK Reproductive Justice Now in Atlanta. She thinks that while Milano and company’s hearts may be in the right place, a boycott under the present conditions wouldn’t help defeat the abortion ban.

“I believe that when we talk about boycotting Georgia, we’re forgetting about the people who live here and don’t support this bill, who are actively advocating against this bill, who are already going to be impacted by this bill, and who you’re going to further marginalize or make their lives harder by boycotting Georgia,” Agbo told Autostraddle.

Eshe Shukura, the Georgia State Organizer for URGE (Unite for Reproductive & Gender Equity), a national reproductive justice organization for young people, agrees that a boycott isn’t in the best interest of Georgians right now and says that it would disproportionately impact working-class folks in the film production industry.

“It’s not reproductive justice to ask people to stop working in an industry that is not just about directors, high-level actors, and other people who make so much money in the film industry. It’s about the workers. Are you actually making plans for them? Boycotts are not just one-off things,” Shukura said to me during an interview.

Eshe Shukura and Kae Goode

Shukura’s right. Activism that hurts people on the margins instead of helping them is the exact opposite of reproductive justice. SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective defines reproductive justice as “the human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and sustainable communities.”

Founded by a group of Black women in 1994, reproductive justice differs from reproductive rights in its approach to abortion by not only advocating for people to have the right to have abortions, but also for people to have access to them. It’s a framework and theory that recognizes abortion restrictions don’t exist in a vacuum — they’re just one of many patriarchal tools designed to rob historically marginalized peoples of our right to make decisions about our own bodies.

It’s no coincidence that Black women conceived of reproductive justice. Throughout history, our reproductive organs have been operated on and sterilized under the guise of being done for the common good. In our white supremacist society, Black women know that our bodies are seen as the least valuable and that we’ll always be the first ones harmed by reproductive attacks; thus, we need to be at the forefront fighting against them.

Queer and trans Black women and femme bodies like my own are especially vulnerable in Georgia, yet we’re rarely mentioned in mainstream conversations about the abortion ban. That’s why SPARK centers young queer and trans people of color (QTPOC) in their organizing.

“I feel like a lot of the times we center white women and cis women when we talk about abortion access and abortion rights,” Kae Goode, a Black trans woman and the Trans Leadership Coordinator of SPARK’s Trans Leadership Initiative, told me during an interview.

“We forget about queer and trans people — they have the right to have a family, and they have the right to get pregnant. They also do get pregnant, they also want abortions and seek abortions, and they have partners who seek abortions, so it affects them in so many different ways,” she continued.

Quita Tinsley, a Black queer non-binary femme and the Deputy Director of Access Reproductive Care-Southeast (ARC-SE), an abortion fund that serves Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, Tennessee, and South Carolina, views abortion access as being intricately linked to their queerness and transness.

Quita Tinsley

“In the same way that abortion is criminalized, queerness and transness also is criminalized. At the heart of it, it’s about these systems trying to strip us of our autonomy, our humanity, and erase us,” Tinsley told Autostraddle.

Queer and trans Black women and femmes like Agbo, Shukura, Goode, and Tinsley are on the frontlines of the fight against Georgia’s abortion ban because that’s what reproductive justice asks of them — for the most impacted to move to the front. Although the media has taken a liking to photos of mostly white women dressed like handmaids from “The Handmaid’s Tale” protesting against the ban at the Georgia State Capitol, the world needs to know that queer and trans Black women and femmes are some of the primary architects of this fight.

SPARK, URGE, and ARC-SE are all a part of the Georgia Reproductive Health, Rights, and Justice Coalition, a group of Black, women of color, and QTPOC-led organizations that are mobilizing Georgians against the abortion ban by holding legislators accountable through direct action, media, and other strategies. Each organization plays an integral role in the coalition.

At ARC-SE, Tinsley has found that it’s more important than ever for their hotline to provide reassurance and accurate information to callers seeking funding and logistical support for their abortions because they’re reading scary, confusing headlines about the ban in the media.

“The reality is, abortion is still legal across the country. People in all of the states that have abortion bans are still able to access care in their state within the term limits that their state already had,” Tinsley said.

With URGE, Shukura has collected more than 9,000 #AbortionPositive pledges this year from young people that serve as their commitment to ending attacks on abortion. URGE is also working to shift cultural narratives, including correcting the labeling of HB 481 as the “fetal heartbeat bill” that’s been pervasive in the news.

“It’s not a ‘heartbeat bill.’ That’s playing into believing in this inaccurate science that this is a heartbeat instead of pulsing cells [at six weeks]. We say call it what it is: It’s an abortion ban,” Shukura said.

The coalition’s paying close attention to abortion restrictions passing in other states, which are all a part of a Republican strategy to eventually overturn Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court decision that legalized abortion. As of the date this story was published, 11 states have passed abortion restrictions this year, with some of them passing “trigger laws” that would automatically ban abortion in their states if Roe v. Wade was overturned.

A national movement to end abortion restrictions led by the grassroots is brewing. The nationwide Week of Solidarity to Defend Abortion from May 20-26, which more than 70 organizations signed onto, is proof of this. In honor of the week, activists held a #StopTheBans demonstration and rally on May 21 at the Georgia State Capitol.

Agbo, who spoke at the rally, says that hundreds of people were in attendance.

“It really was a call to all of those who are scared for this bill that a lot of people care and that we’re not just going to stop. We’re ready, and we’re not going to take this lying down,” Agbo said.

I believe that we can win the fight against Georgia’s abortion ban if we take the lead of queer and trans Black women and femme reproductive justice organizers — but they can’t lead us to a victory without sufficient resources. I can’t stress enough how key it is to donate your money and time to reproductive justice organizations in Georgia and beyond.

Money with no strings attached from everyday people is important to these organizations’ survival. Giving to SPARK and URGE allows them to mobilize even more folks against the ban and other reproductive oppressions. Contributing to ARC-SE means that you’re funding abortions directly.

If you want to give your coins or labor to reproductive justice efforts in your own backyard, here’s a list of abortion funds across the country and reproductive justice groups in your area are just a Google search away. Consider offering practical support to abortion seekers at your local abortion fund in the form of rides, childcare, or care packages.

Reproductive justice activists in Georgia don’t plan on ending their movement against abortion restrictions any time soon. No matter what lawmakers may do, they’ll continue aiming to make sure folks on the margins can secure access to abortion and other reproductive freedoms.

And if you ever feel scared for our reproductive futures, take heed to Tinsley’s words — they told me that now isn’t a time for fear, but instead, a time to show up for and support one another.

“I think about the ways in the South that Black people have always shown up and taken care of each other. Now is the moment for us to follow in those traditions of taking care of each other because, clearly, these systems won’t take care of us.”

These Five Black LGBTQ+ Activists Are Literally Saving The Planet

Talking about extinction isn’t mere hyperbole: According to a new United Nations assessment, as many as one million plant and animal species are at risk of extinction due to the actions of humans. Ironically, the people who’ve harmed our ecosystems most are the ones being paid to defend them.

People like me aren’t reflected on the staffs of organizations that proclaim to have the solutions to environmental problems. The Green 2.0 Working Group found that only 16% of staff at environmental nonprofits, foundations, and government agencies are people of color. Too many of these organizations refuse to acknowledge that climate change and pollution are rooted in environmental racism.

The only ones who can bring our planet back from the brink are Black and Brown descendants of peoples who lived harmoniously with land. As a Black queer non-binary woman, I wholly trust in the creativity, righteous rage, and resilience of Black LGBTQ+ people to reverse the devastating effects that colonialism and industrialization have wrought on our planet.

Black LGBTQ+ people may not be well-represented in mainstream environmental organizations, but the world needs to know that we’re creating our own environmental institutions and interventions that center the most marginalized among us. If you’re wondering what true environmental justice looks like, read on to meet five Black queer, transgender, and gender nonconforming activists and community organizers who are literally saving the earth.

![]()

“and when we speak we are afraid

our words will not be heard

nor welcomed

but when we are silent

we are still afraid

So it is better to speak

remembering

we were never meant to survive.” – Audre Lorde, A Litany for Survival

![]()

Asha Carter

Instagram: @suitlalumiere // @dc_greens

Pronouns: She // Her

At 14-years-old, Asha Carter traveled to the Galápagos Islands, where the government carefully protects the ecosystems, and 95% of the islands’ pre-human biodiversity remains intact. The trip showed Carter that it was possible to live in harmony and balance with land, a stark contrast to how we live in the United States, and sent her down a career path where she works to figure out how environmental justice (EJ) might liberate marginalized people.

“My work has really been directed by ‘how do we live in harmony with where we are?’ and understanding that so many of us for hundreds of years have been pillaged and extracted from in order to build what exists right now,” Carter told me during a phone interview.

As the Food Justice Strategist at DC Greens, Carter helps people and organizations move closer to racial equity through a food justice lens that allocates tools and resources to those who’ve been most impacted by systemic oppression. In her capacity as a social justice educator, community organizer, and EJ advocate, she’s surrounded by fellow Black queer women doing visionary EJ work, which she attributes to their lived experiences of navigating multiple oppressions.

“There are hella queer Black women in this space who are articulating their visions for the future, who are working with other people to get land, who are doing the work of getting each other free, and I am awed by that,” Carter said. “I think that there’s something to it that you have a bunch of queer Black women who ended up in this space.”

Carter’s political analysis has been shaped by peers, such as the folks at the National Black Food and Justice Alliance, a coalition of Black-led organizations who organize for food sovereignty, land, and justice. It’s also been influenced by her family: Her grandmother organized with the Black Panthers, and her parents brought her along to civil rights demonstrations as a child. Carter’s deep knowledge of racial justice organizing and its history makes her a powerful force for environmental justice. It even earned her a spot at the Environmental Protection Agency during the Obama administration.

![]()

“History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.” – Maya Angelou

![]()

Dominique Hazzard

Twitter: @hazzardeuce

Instagram: @peculiarivy

Website

Pronouns: She // Her

Food makes Dominique Hazzard tick. Ensuring that Black people have equitable access to food, especially her neighbors in Ward 8 of Washington, D.C., is the cornerstone of her organizing.

“Food is important to me as both one of the most intimate and universal parts of being human and as a place where some of our most pressing issues – capitalism, climate change, soil conservation, poverty, prisons – converge,” Hazzard wrote to me.

Drawing from her passion for getting fresh, healthy foods to her people, in 2017, Hazzard helped lead the Grocery Walk, a two-mile walk of nearly 500 Washingtonians between downtown Anacostia and Ward 8’s only grocery store in the name of food justice. Demands from the historic walk included having land set aside for urban agriculture, support for cooperative businesses, and funding for food programs.

Her lived experiences of Blackness and queerness allow Hazzard to conceive of such demands. They help her see that another word is possible and dare her to believe that the side of Black liberation will win. She learned how to organize within the youth climate movement and currently calls BYP100, a member-based organization of Black youth activists creating justice and freedom for all Black people, her organizing home.

Hazzard’s not only engaged in freedom struggle on the ground – the historian-in-training researches migration and the Black family, racism and real estate in the U.S., environmental history, and food history as a history doctoral student at John Hopkins University. She also helps nonprofits strategize around anti-racism and being accountable to the communities impacted by their work.

“I do this work because I believe that building a food system that is good for people and the earth is possible, because Ward 8 is my home, and because of my deep love for Black people,” Hazzard said.

![]()

“All that you touch you Change. All that you Change Changes you. The only lasting truth is Change. God Is Change.” – Octavia Butler, Parable of the Sower

![]()

Dean Jackson

Instagram: @qtpocfarmer

Pronouns: They // Them

In the historically Black Hilltop neighborhood in Tacoma, Wa., the traditional lands of the Puyallup tribe, urban farmer Dean Jackson is busy creating things that the world needs. Hilltop Urban Gardens (HUG), a food sovereignty and racial and economic justice organization, was born out of Jackson’s vision to create a community resource during the Great Recession. If you’re looking for a textbook example of queer resiliency, simply refer to HUG’s origin story: Jackson is a Black queer, trans, and non-binary person – someone often told that they shouldn’t exist – who visioned something into reality out of necessity.

HUG’s programs are specific responses to the needs of their neighborhood. The Urban Farm Network, which started with Jackson building gardens in their neighbors’ parking strips, feeds the neighborhood – residents exchange their “time, talent, or treasure” for produce in lieu of money at HUG’s farm stand.

The organization’s Black Mycelium Project, which works closely with a group of indigenous herbalists, allows Black people to reconnect with land on their own terms; re-teaching them how to grow food and how to grow, prepare, and use plant medicines. Practicing Black and indigenous solidarity is a priority at HUG, which also runs a program for Black and indigenous youth to learn about the history of Black and indigenous organizing.

Furthermore, HUG engages in land and housing liberation work that defends, preserves, and increases Black-owned land in the rapidly gentrifying Hilltop neighborhood. Jackson says that while gentrification and displacement are huge environmental justice issues, they have a hard time convincing other environmental organizations of this. These organizations’ refusal to put gentrification and displacement on their agendas is ultimately rooted in racism.

“It might be easier to restore a waterway to be a salmon-breeding area than it is to address gentrification, but in the meantime, by environmental organizations not doing that, it looks very much like a demonstration of anti-Blackness,” Jackson stated to me during a phone interview.

Another way Jackson sees anti-Blackness manifest in the realm of environmentalism is white organizations co-opting EJ. They want these white organizers to know that what they’re doing isn’t EJ – what they’re doing is practicing white supremacy.

“White people can move their resources to EJ work,” Jackson said. “They can use their positionality to support EJ work, but they can’t actually lead it.”

![]()

“Dear seed,

Thank you for such strong roots.

Love always,

The fruit.” – Self

![]()

Jeaninne Kayembe

Instagram: @_oro5_

Pronouns: She // Her, They // Them

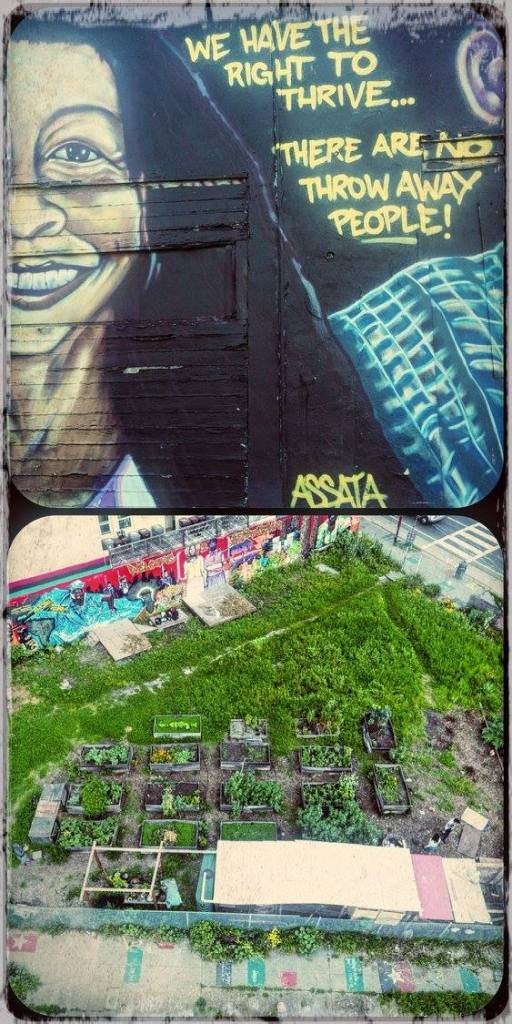

At the intersection of public art, food security, community safety, and youth organizing, you’ll find Jeaninne Kayembe, a queer Black and Asian-Pacific Islander woman who prioritizes creativity as a tool in solving the issues that marginalized people face. At the age of 19 Kayembe co-founded Urban Creators, a North Philadelphia organization that’s transformed over three acres of blighted land into the Life Do Grow Farm, which now yields fresh produce for dozens of local families each year.

Life Do Grow Farm is a site where cultural and social change is created. The work there has contributed to a 40% decrease in violent crime in the immediate area. It’s a space where Black and Brown young people can feel safe and become leaders, having employed and provided leadership opportunities to 117 youth. The farm also serves as a platform for artists to showcase their work at events such as the HoodStock Community and Arts Festival, which Kayembe executive produces, and is the foundation of Kayembe’s creative placemaking practice.

Urban Creators is a place where political education happens organically, like through Kayembe’s conversations with young men of color who work on the farm about cultural and social issues that can be difficult to discuss, such as queerness and rape culture.

Off of the farm, Kayembe often finds herself educating rooms full of people who aren’t used to seeing a queer woman of color speak truth to power. Teaching white environmentalists about the nuanced experiences of young POC requires her to code switch and navigate many different terrains.

“It has been my work to build that bridge to young people of color so they see their place and face in this movement,” Kayembe told me.

Building relationships lies at the heart of Kayembe’s activism. What makes Urban Creators’ work so impactful is their commitment to deepening their relationships within the organization, with the community at-large, and with the local environment. Through relationship-building, growing food, and making public art to facilitate a safer community, Kayembe’s aiming to change the narrative of what environmental justice can mean.

![]()

“I believe all organizing is science fiction. Trying to create a world that we’ve never experienced and never seen is a science-fictional activity.” – adrienne maree brown

![]()

Rachel Stevens

Website

Pronouns: She // Her, They // Them

Rachel Stevens wants everyone to feel safe – no easy feat during these times we’re living in. In her current home Los Angeles, in central Florida where she’s from, and in the Amazon rainforest where she completed a service learning project – she’s witnessed up close and personal how colonization hurts Black, Brown, and indigenous peoples and their land. This is why Stevens’ praxis is grounded in protecting both the earth and humans; she views them as interconnected.

For Stevens, the street violence she experiences as a multiracial Black, queer, non-binary, genderfluid femme is deeply tied to the harm she experiences due to environmental contamination.

“We can’t look at how these oil industries are contaminating the air and making it hard to breathe and seeing that that’s a breach of safety without seeing that patriarchy is also a breach of safety for people, as well as white supremacy,” Stevens said to me during a phone interview.

Stevens carried her experiences of interpersonal violence and systemic oppression with her while organizing with STAND-L.A. (Stand Together Against Neighborhood Drilling), a coalition of community members who live or have lived near drill sites that fight to end oil extraction in LA. As part of a STAND-L.A. campaign, Stevens supported residents in pressuring LA City Council to require a 2,500-foot health and safety buffer be put in place between oil drilling operations and people’s homes. During this campaign, she recognized the different ways in which the residents’ struggle for safety intersected with her own.

In their environmental justice work, Stevens sees a need for sustainability not only in how we treat the earth, but also in how we treat each other. They hope to see more people within justice movements prioritize building sustainable relationships and practicing community care.

“We really need to care deeply for each other, fight for each other, see our inherent dignity in each other, and admit that we need each other fiercely if we’re going to win and create this sci-fi world of safety that we’re striving for,” Stevens said. 🌲

edited by carmen.

My Old Elementary School Is a Toxic Waste Site and Other Environmental Nightmares

My elementary school playground was as ordinary as it gets. It had a jungle gym, seesaws, a slide, and rowdy kids all over. I was usually found gabbing with my girl gang about the latest issue of Seventeen Magazine in some far corner of the playground. All was well with the world, or so I thought.

I had no clue that I was playing on top of one of the country’s most toxic waste sites. I didn’t know that my hometown, Brunswick, Georgia, is just one of many Black communities in the US facing environmental degradation. For example, less than an hour away from where my father and grandmother live in rural Eastern North Carolina, Black neighborhoods are being sprayed with pig feces and urine produced from nearby industrial hog farms. After three years of crisis, the predominantly Black residents of Flint, Michigan still don’t have lead-free water. Environmental problems are hitting Black neighborhoods particularly hard, but going unresolved because Black lives are deemed less valuable than others. A lot of us are being left in the dark about harm being done to our environment.

Growing up, I never heard bad things about Brunswick’s smelly plants and their emissions that painted our air brown. Since these industries created living wage jobs for working-class men, folks shed a positive light on them. However, as an adult, I learned that my hometown has paid an enormous price for supporting polluting companies, such as Hercules Inc., a chemical and munitions manufacturer that operated a plant in Brunswick from 1920 until being bought out in 2010.

At the Hercules plant, workers extracted substances from pine stumps to be used in various commercial products. One of those substances was toxaphene, a pesticide that became popular with Southern cotton and soybean farmers in the 1960s and 1970s. Over the years, studies found that toxaphene exposure causes thyroid and liver tumors in animals and seizures and respiratory problems in humans. The Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry warns, “Breathing, eating, or drinking high levels of toxaphene could damage the nervous system, the liver, and kidneys, and even cause death.” Today, toxaphene is internationally banned, but by the time Hercules stopped producing it in 1980, toxaphene waste had already seeped into the soil beneath the plant and had also been dumped into a local creek and a landfill.

The landfill, called Hercules 009 Landfill site, was named one of the most hazardous waste sites in the US by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1984. At the southeastern border of the site sits Altama Elementary School, where I attended school from 1992 to 1998.

Neesha during their time at Altama Elementary school circa about 1996

My two older sisters and younger brother are also Altama alumni, and my maternal grandmother worked in the school’s cafeteria for more than a decade. We never heard about toxaphene waste traveling through a drainage ditch from the landfill onto our school grounds. Turns out that my formative years were spent playing in contaminated soil.

Hercules 009 is just one of four Superfund sites in Brunswick. The federal Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 established the Superfund program, which calls for the cleanup of the most toxic waste sites in the country. Superfund sites are potentially harmful to humans, animals, and the environment.

A 2007 map of Hercules 009 Landfill Superfund Site via Glynn Environmental Coalition

During the mid-1990s, toxaphene waste was removed from the back of Altama, and the EPA website currently states, “Site contamination does not currently threaten people living and working near the site.”

Although conditions are reportedly safe, project manager Daniel Parshley from the Glynn Environmental Coalition (GEC), a local environmental nonprofit, says the soil at the school has never been appropriately tested for contaminants. GEC is involved in community organizing, advocacy, and providing technical assistance to Superfund sites to assure “a clean environment and healthy economy for citizens of Coastal Georgia.”

In 2005, the EPA Office of Inspector General found that the method being used by the EPA, Hercules, and the GA Environmental Protection Division (EPD) to analyze the amount of toxaphene in the soil at Altama was erroneous and inadequate. This flawed method has also been used at Hercules’ other Superfund site in Brunswick.

Ever since learning about my alma mater’s toxic history, I worry whether me and my siblings were affected by these chemicals. I speculate whether toxaphene exposure contributed to my grandmother’s death from cancer in 2006. Should my family follow the lead of others who are suing because of exposure to pollution from Hercules?

Whether we have a case or not, the former Hercules plant is still a cause for concern in my hometown. Pinova Inc., the company that bought out the plant in 2010, was issued an enforcement order by the state EPD for noncompliance with their air permit in October 2016 and then another one this past December for a long list of Air Quality Act violations. The trend of corporations putting themselves before the health and wellness of Black folks in Brunswick is alive and well.

Rev. Jeffery Muchison is a Black pastor in Brunswick who wants to see big business and city government do right by his neighborhood. A member of the Magnolia Park/College Park Neighborhood Planning Assembly (MPCPNPA), Muchison is a witness to how corporate decisions, as well as government inaction, negatively impact the health and well-being of his neighbors.

The assembly’s currently fighting against a waste and recycling facility called Liberty Roll-Offs & Recycling just north of Magnolia Park, a historically Black neighborhood. When Liberty Roll-Offs opened in 2008, only construction materials were recycled there. Over time, the facility expanded to receiving solid waste materials, bringing a distinct stench into the neighborhood along with other nuisances. Although the facility has brought 50 to 60 new jobs into the neighborhood, it’s been at the expense of residents.

“Those residents have been complaining about rodents, the odor, the big trucks that come out from the company,” Muchison says. “Sometimes liquids are draining out of the trucks onto the streets, and it’s got a terrible odor to it.”

Neighborhood residents with asthma have gotten sicker since the expansion of Liberty Roll-Offs. The facility’s rotten cabbage smell, rats, noisy trucks, and fires from their wood chip stockpiles are deteriorating the quality of life of the entire neighborhood. Magnolia Park is unfortunately in a worse predicament than when I was baby-sat there more than 20 years ago.

Liberty Roll-Offs claims that none of their waste drains into the ditch surrounding Magnolia Park, but MPCPNPA members aren’t convinced. Members also aren’t sure if the company has a municipal waste permit, which it should have since they receive municipal waste.

The assembly’s working in partnership with GEC to help spread the word about their demand for the city: To relocate Liberty Roll-Offs far, far away from residential neighborhoods. To forward this goal, members are exploring their legal options, disseminating a petition, and calling for testing of the ditch.

In College Park, a Black neighborhood only a few miles from Magnolia Park, the assembly’s tackling another environmental crisis. Although hurricanes typically weaken into tropical storms before landing in Brunswick, these storms are still heavy enough to cause major damage, including in College Park. When Tropical Storm Irma hit the subdivision this past September, about 32 homes flooded with up to a foot-and-a-half of water.

Since Tropical Storm Tammy in 2005, some houses have flooded four or five times. Muchison’s seen tropical storms in Brunswick get stronger over the years thanks to climate change, so the neighborhood needs a fix now more than ever.

College Park after Tropical Storm Irma. Photo via The Brunswick News

Through their research, the MPCPNPA found that most of the drainage in the area, including from businesses, empties into College Park’s drain. Because the drain isn’t big enough, more water than it can handle comes in during storms, resulting in excessive flooding. In Parshley’s opinion, the culprit of this problem is “the failure of zoning and planning to do adequate stormwater planning.”

MPCPNPA members and supporters have packed City Hall to address the flooding in the past. In June 2017, the city commission contracted with an engineering firm to help with College Park’s drainage issue, and the assembly plans to hold the city accountable until the problem is fixed.

According to an email from City Engineer Garrow Alberson to Muchison, data collection, field investigation, and hydraulic modeling to analyze the drainage system have been completed. There will be a final report on the issue soon. No matter the outcome of the study, it’s still a win for the MPCPNPA because it wouldn’t have happened without their grassroots activism.

The Black residents of Brunswick deserve a clean and safe environment. But as natural disasters increase due to climate change deniers-in-power, their neighborhoods will continue being hit the hardest. Their town, once home to the now-extinct Timucua peoples, will continue to be treated like an endless commodity by corporations under Donald Trump’s presidential administration.

Thankfully community activists aren’t letting the naysayers and polluters win without a fight. As a descendant of people who lived off this land for generations after being stolen from theirs, I know that I, too, have a role in healing the environmental havoc that capitalism and racism has wrought in my birthplace.

Trumpcare Is an Attack on Trans People of Color. Let’s Fight Like Hell Against It.

Republicans claim to fight for the protection of lives, but the revised Senate health care bill released on Thursday indicates otherwise. Based on a previous version of the bill, the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA) threatens to leave 22 million people without health care by 2026, according to the Congressional Budget Office. The CBO’s report of how much the revised bill would cost and how many people would lose insurance is expected on Monday. Defeating this bill is a matter of life and death to the transgender, gender non-conforming and intersex people of color (TPOC) who depend on Medicaid to survive.

“It’s just a part of genocide — people gentrifying our health care and taking it from us and telling us how we can have it and how we can’t,” Jade Dynasty told Autostraddle. Dynasty is a 22-year-old queer, trans mixed-race nightlife performer, producer, dancer, choreographer and activist based in Seattle who’s currently covered by Medicaid.

Jade Dynasty. Photo via Gender Justice League

Dynasty benefited from the Medicaid expansion established in 2014 by former President Obama’s Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, which allowed states to extend Medicaid coverage to adults without dependent children with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level. Washington is one of the 31 states (plus the District of Columbia) whose legislatures voted to accept federal money for the expansion. Historically, Medicaid was only available to single parents, disabled folks and low-income seniors but the expansion allowed more than 11 million people, including trans people, to become eligible and receive vital health care.

Under the new federal regulations, Medicaid was extended to any adult with an annual income of less than about $16,643. For comparison, before Medicaid expansion, eligibility was 100% of the federal poverty level or about $12,060. The expansion has been a lifeline for many queer and trans people, as they are more likely than non-LGBT people to live in poverty, especially trans people of color. According to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, trans people of color — including Latinx (43%), American Indian (41%), multiracial (40%), and Black (38%) respondents — were up to three times as likely as the U.S. population (14%) to be living in poverty. In addition, the unemployment rate among respondents (15%) was three times higher than the unemployment rate in the U.S. population (5%), with Middle Eastern, American Indian, multiracial, Latinx, and Black respondents experiencing higher rates of unemployment. Thirteen percent of respondents to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey reported being covered by Medicaid; that’s ten percent more than in 2011 (before Obamacare).

If implemented, Trumpcare would freeze enrollment and gut $770 billion of federal funding from Medicaid in the next ten years, stripping health benefits from 15 million Americans.

“For people who are immigrants, of color, poor and who don’t have higher educations, it is hard for people to keep up with the potential roll backs and all the regulations changing. All laws should be accessible and clear for all people, and the uncertainty in the political climate only compounds the barriers facing the TGNCI community.”

Kyle Rapiñan and Stefanie Rivera, both directors at the Sylvia Rivera Law Project (SRLP) — a NYC-based legal representation and advocacy group named for the patron saint of trans rights — agree that trans, gender non-conforming and intersex individuals will be disparately impacted if Medicaid expansion is rolled back.

In a joint email statement to Autostraddle, Rapiñan and Rivera wrote, “For people who are immigrants, of color, poor and who don’t have higher educations, it is hard for people to keep up with the potential roll backs and all the regulations changing. All laws should be accessible and clear for all people, and the uncertainty in the political climate only compounds the barriers facing the TGNCI community.”

The Senate health care bill delivers another blow to trans health care by stripping Planned Parenthood of its federal funding for one year. More than 40 percent of Planned Parenthood’s budget comes from Medicaid reimbursements, including from patients seeking transition-related care. Planned Parenthood offers hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in at least 16 states and transition-related care at about 65 Planned Parenthood locations. Some trans and gender-variant people opt to take HRT so their appearance more closely aligns with their gender identity. From 2013 to 2015, there was an 80 percent increase in Planned Parenthood affiliates that reported offering HRT. These medications not only allow trans people to feel like themselves, but can also increase their safety in public spaces.

“The more ‘passable’ you are, the safer that it is for you in certain situations,” says Dynasty, who also notes that straddling the gender binary is more accepted in cities like Seattle that have protections for the trans community.

When trans people who rely on HRT cannot access it legally, turning to the black market for hormones may become their last resort. Several online pharmacy websites located outside of the U.S. sell illegal hormones. The SLRP wrote that when trans and gender non-conforming people are forced to obtain black market hormones, they are exposed to the risks of lifelong health complications and even death.

In an email to Autostraddle, Vin Tangpricha, MD, PhD, Endocrinologist and President Elect of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), explained how black market hormones put trans people at risk.

“‘Black market’ hormones are unsafe because they may not contain the hormones in the appropriate concentrations or may have been contaminated by unsafe handling and/or storage conditions,” Tangpricha said. “Even worse, the ‘black market’ hormones might not even have any hormones in them. The costs of hormones are relatively inexpensive and many free care clinics are now providing transgender medicine services. I highly recommend that people seek help from a medical professional to obtain low or no-cost hormone therapy.”

While Washington is one of 12 states to ban exclusions of transition-related care, such as HRT, in both private health insurance and Medicaid coverage, TPOC in the state who access health care still encounter racist, transphobic health care providers who are incompetent in trans issues. Dynasty says she’s had only one doctor, a cisgender white woman (she’s never had a trans doctor), in Seattle treat her like a human being, but the doctor can rarely see her because her clinic is across town from where Dynasty lives.

Zoe Samudzi, a 24-year-old writer and PhD student in medical sociology with an emphasis on trans health care at the University of California San Francisco, says that preventative care becomes difficult for trans people when they anticipate experiencing transphobia or trans-antagonism where they have to teach doctors.

“Trans folks have to be both the patient and the educator,” Samudzi says. “When it comes to trans folks of color, all of these structural issues around gender identity get compounded by these experiences of racism.”

TPOC are more likely to receive culturally incompetent health care than their white trans peers, and Black and Latinx trans folks are more likely to lack access to healthcare. The National Transgender Discrimination Survey found that 12 percent of white respondents lacked health insurance compared to 20 percent of Black respondents and 17 percent of Latinx respondents. 19 percent of respondents to the same survey reported being denied healthcare because of their gender identity.

“We have a responsibility as cis folks to do the work to dismantle these systems of domination that we are beneficiaries of and that we’re complicit in.”

Studies on trans people and health care are usually biased and often dreary, but they aren’t able to measure the enormous amount of resilience within TPOC that enables them to survive. Dynasty is just one of countless TPOC who unapologetically advocate for what they need within community and on a legislative level. They shouldn’t have to fight for basic human rights and cisgender people who identify as “allies” or “accomplices” have a duty to speak up when their rights are under attack, a principle Samudzi applies to her research.

“I am the beneficiary of this biomedical system that marginalizes trans people and makes my cis body a superior body,” says Samudzi, a cisgender queer Black woman. “We have a responsibility as cis folks to do the work to dismantle these systems of domination that we are beneficiaries of and that we’re complicit in.”

In their email statement, SRLP staff wrote, “Trans people and gender non-conforming people should be afforded high quality medical care and should be free from harm — we all must keep organizing to prevent state and interpersonal violence.”

This is what it will take to secure affordable, accessible health care and safer spaces for all TPOC. A quick action you can take is calling your senators and urging them to vote “no” on the BCRA and then asking all of your friends, co-workers, and schoolmates to do the same. Make your calls as soon as possible because Republicans are trying to rush the bill to a vote. If you have more time on your hands, get creative with your resistance, like the 60 disability rights activists who staged a die-in outside of Republican Sen. Mitch McConnell’s office on June 22 to oppose the bill. You don’t have to get arrested like they did, but at least use your talents and your privilege to be in solidarity with TPOC.

And if all else fails, Dynasty suggests that cis people can always help TPOC in their community take care of themselves by giving them money.

“As a trans person, this is a process. Makeup costs money, getting your hair done costs money, getting your nails done costs money, being hygienic costs money,” Dynasty says. “If you’re a trans person, and you’re not on your shit, people view you as dirty or like you’re not doing it right.”

TPOC need our money, and they need it now. Far too many TPOC such as Princess Harmony, a 25-year-old Afro-Latina writer based in Philadelphia, are forced to raise money on crowdfunding sites simply to survive. A social worker is currently helping her obtain Medicaid, an attempt that will be for naught if Republicans get their way. While the fight against the dismantling of Medicaid is most urgent, we can’t forget that universal health care should be our long-term goal if we truly believe that health care is a human right.

“I think that the only health care reform bill that’s truly good for QTPOC is the Medicare for All bill that was introduced in Congress,” says Harmony.

According to National Nurses United, Medicare for All is a health care system that would require each state to “set up and administer comprehensive healthcare services as an entitlement for all, through a progressively financed, single-payer system, administered by the states.” Single-payer health care may be our best hope for the future, but unfortunately, Trumpcare is our immediate present. Trans people, especially TPOC, have enough to worry about without losing their health care.

It’s time to fight like hell to prevent the GOP’s latest bill from becoming law, just like Sylvia Rivera fought for liberation for us all.

Get Ready, Stay Ready: Allied Media Conference Reps the QTPOC Future

Neesha and KP, two QTPOC organizers reflect on the 2017 Allied Media Conference.

KP and Neesha

Neesha

It’s easy to forget that another world is possible as bigotry and hate violence become more en vogue by the second. As a Black queer non-binary person living in the majority-white city of Seattle, I often fear for my safety in public places and for the safety of those I care about. My identities garner hostility in LGBTQ+ spaces that are predominantly white, as well as in people of color spaces that center cisgender heteronormativity. Upon attending the Allied Media Conference (AMC) at Wayne State University in Detroit for the first time ever a couple of weeks ago, I found that it’s a space like no other, one where people of color and trans and queer folks are not only visible, but are also the leaders. Now in its 19th year, AMC is a microcosm of a world where historically oppressed groups are empowered to share our stories and where our narratives are deemed important and necessary. The conference serves as a portal to collective dreaming and scheming where barriers become bridges to a more just future.

Being a forever curious Gemini, I asked friends who’d attended the AMC what to expect before my trip there. Most of them mentioned that conference attendees wear the flyest looks, so I packed with much care. It felt good presenting my most fashionable self at AMC as I rubbed shoulders with social media crushes and creators whose work makes me swoon. For me, the conference’s opening ceremony was akin to a child’s first time at Disney World, and I hungrily consumed the offerings of brilliant Black and Brown folks that night at the Detroit Film Theatre, including a performance of “Hijabi” by Mona Haydar, a Syrian-American rapper from Flint, Mich. and a keynote speech ruminating on the meaning of collective power by one of Black Lives Matters’ founders, Alicia Garza.

Black queer sci-fi writer, healer, and facilitator adrienne maree brown acted as one of the hostesses of the opening ceremony, effortlessly moving along a jam-packed program. I started reading brown’s new book, Emergent Strategy, on the plane to Detroit, and it set the tone of my entire trip. While the vast amount of enticing workshops at the AMC prevented me from attending one of her sessions (thankfully, her Spells for Radicals workshop is documented here), brown’s ideas around emergent strategy and critical connections resonated with me while navigating the conference. Emergent strategies are organic strategies that take shape from our everyday interactions in communities and critical connections are the deep relationships we forge with others that result in social change.

“Get ready, stay ready,” the theme of this year’s conference, also played on repeat in my head as I soaked up new information to bolster my community organizing work by attending workshops about developing resources for social movements, facilitating community accountability processes, and implementing collective facilitation strategies. I realized that a huge part of getting ready and staying ready is for folks on the margins to be able to communicate our own stories to the world. I attended a session led by Black Trans Media entitled “Black Trans Futures” which reaffirmed my commitment to creating and supporting Black trans and queer media-making. The workshop’s facilitators, Sasha Alexander, Olympia Perez, and Amari Xola Rasin, stressed how essential their work is during a time when non-Black trans media organizations have no qualms with exploiting Black trans stories. During their workshop, we listened and watched Black Trans Media’s interviews with Black trans geniuses, including Kokumo, a trans woman artist and activist who I look forward to seeing perform in Seattle next month in BlackTransMagick: A Journey Towards Liberation. Perez shared a poem she wrote about the ugly insults and stares she endures in public as an out and proud Black trans woman, as well as her experimental short film called I AM HEAR featuring Black trans women in her community. The workshop ended with brainstorming about what kind of representations of Black trans people are absent in the media and how to get more resources to Black trans people to create these missing narratives.

While in Detroit for the AMC, a tragedy occurred back home in Seattle that demonstrated both the importance of communities creating their own media and of being ready to mobilize against oppression at any moment. On the morning of June 18, police shot and killed Charleena Lyles, a pregnant 30-year-old Black mother of four struggling with mental illness, in her North Seattle apartment in front of her children. As a Black femme-appearing person who turned 30 during the AMC and also has mental health struggles, the news of Charleena’s murder shook me to my core. Just the day before, I’d mourned the non-conviction of the police officer who killed a Black man in Minnesota named Philando Castile alongside fellow AMC-goers at a vigil held by Families United 4 Justice, a group of families affected by police violence in NY State. Charleena’s death weighed heavily on me as I pictured myself in her shoes, and the insensitive, anti-Black reporting of her murder in the mainstream media only magnified my grief, including a Seattle Times headline that read “Knife-wielding woman killed by officers she called…” Mainstream media blames the oppressed for our own oppression, which speaks to the very real need for spaces like the AMC where community-led alternatives to mainstream media are taught and practiced.

Families United 4 Justice

Luckily, I traveled to and through-out Detroit with a comrade from Seattle, KP, who made sure I had what I needed to process my feelings, including a makeshift altar in our hotel room to honor Charleena’s memory. In my hotel room, I pressed my rose quartz stone to my palm, listened to the Steven Universe soundtrack, and tried to breathe through my pain. As soon as my wife picked KP and I up from our return flight to Seattle, we headed to a vigil at Charleena’s apartment. To our surprise, as we approached our destination, we spotted a sea of protestors marching down the street, including many of our friends. Charleena’s family and friends led the way as they chanted, clapped, and danced in the name of justice. I chanted along with them as I recorded the action, musing at how quickly Black grief can morph into Black joy.

The looks of resilience on the protesters’ faces mirrored the faces of the local Black musicians I watched perform at the end of the AMC closing celebration. As soon as I recognized the harpist, a trans woman named Ahya Simone, was playing the tune of Future’s song “Maskoff,” I started to get my life. “Get ready, stay ready until we’re all free,” crooned the songstress Britney Stoney to the sounds of the harp. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw the Church of the Messiah Drumline approach the stage, and they began to drum to the beat of Stoney’s voice. The drumline led us all outside of the auditorium, where they performed as the rest of us enjoyed their entertainment while the sun kissed our skin.

In that moment, I felt full of hope and became even fuller when I remembered the next day was Juneteenth, a holiday celebrated by Black Americans to commemorate the day the Emancipation Proclamation finally reached the enslaved people of Galveston, TX. As I figure out how to best show up for Charleena during these post-AMC days, I hold my joyful memories of the conference close to me and lean on them for inspiration whenever I feel like giving up. I cherish them as I continue building towards a future that looks like the AMC: Black, Brown, trans, and queer as f*ck. I’m already looking forward to what the AMC holds in store for its 20th anniversary next year, and I hope to see some of y’all there!

Katrina (KP)

As a cultural worker, I long for spaces where our artistry is not seen as separate from our organizing, where the political is not only personal, but encompasses our full emotional and spiritual selves. If we are creating a world where no one is disposable, then we must also acknowledge all parts of ourselves — how we may show up in ways that are not always the best, but in the words of Ella Baker, “We are here. We matter. And we can change things.” Yes, even the messy and the petty. Because those are moments that are key to transformation. At the Allied Media Conference, transformation is not only possible, but reverberates across time and space with a resonance that is deeply felt.

I attended the conference for the first time in 2014. I had never seen or even imagined anything like it before. In one of the sessions, there was a panel that talked about the importance of place-based narratives in movement- building, featuring dream hampton, and it really hit home. As someone who comes from a legacy of colonization and forced migration, I have always struggled with my place in the world. More specifically, my place as a Pilipinx migrant settler in Seattle, who felt at home for the first time living on Beacon Hill, a neighborhood previously composed of mostly Latinx and Asians with a strong Filipino presence. As a 21-year-old college student leaving home for the first time, I could walk a couple of blocks to eat Filipino food and be in my feels. Ten years later, many of the POC- owned businesses have closed down due to rent increases and the neighborhood has a much different vibe.

While listening to stories of Detroit’s resistance to gentrification, I reflected on my work around resisting the displacement of black folks and people of color in Seattle, as well as fighting for land and sovereignty of Filipino people while holding the complexities of diaspora. I always saw Seattle as one step to elsewhere, a bigger city or ideally, building a home back in the Philippines. Yet Seattle is where I have come into my identities as a queer non-binary Pilipinx immigrant and came to understand my place in the movement for liberation. It is where my daily lived experiences are woven into the fabric of resistance.

I also had the honor of visiting Grace Lee Boggs in her home for a group Q&A session. Listening to her speak on the long history of organizing in Detroit and her thoughts on the current political conditions was mind blowing because she is brilliant and has witnessed and taken part in so much history. She joined the ancestors not long after.

What I took back from that conference became integral to how I moved forward in my work, and the next few years were spent fine tuning these lessons to apply to Seattle organizing conditions. I have since been following the development of Emergent Strategy and as I read the book, I can see the series of events that led to the founding collective of Queer the Land (QTL), which is what brought Neesha and I to the AMC. QTL is centered on the idea of claiming space, to fight the displacement of our communities in Seattle and the need to have organizing that centers QTPOC, meets our basic needs, and honors how QTPOC have been holding down our communities on so many levels while also leading these movements for change.

Being at the AMC feels like the space QTL is in the process of creating. I was deeply moved by how AMC is grounded in our collective power to manifest a just and abundant world. Being there feels like we are dreaming this world into being. I was lucky enough to straggle in late to Alexis Pauline Gumbs session “From Media to Medium: Creating Revolutionary Oracle” and it was life giving. I went in tired and scattered and left feeling grounded and full. In that session, we tuned into our individual and collective power as oracle and channeled ancestors in response to questions that were pressing to our current conditions. I was affirmed that rest and reflection is essential to me (and all of us) in understanding our purpose. I also felt the past, present and future all at once while listening to her channeling ancestors’ wisdom — something that only happens when I am fully present in myself and attuned to the universe.

The exuberance I felt throughout the conference carried into the closing plenary and ceremony, which was abundant with hope and possibility. I remember walking back to the car with friends, bodies exhausted and spirits elated, thinking about all the things to bring back to our work in Seattle. Hearing about the murder of Charleena Lyles and Nabra Hassanen within that hour was jarring and so heartbreaking. The next few days I physically felt ill from the fear gnawing into my stomach — because it is very clear that they are coming for us and I don’t know how long we can withstand these attacks on our humanity. But then I think about our ancestors dreaming us into being while they were under attack and it brings back that feeling of past, present and future in these glorious moments of connection and collective power. This is a gift, one that allows me to live my life as an offering to those who came before and the generations that come after us.

Katrina Pestaño/ KP is a cultural worker and community organizer living in occupied Duwamish territory/ seattle. also known as emcee rogue pinay, KP has been at it since 2007, performing and producing media that weaves counter-narratives of those often invisibilized yet in the front lines of change. KP mobilizes immigrant communities through anti-violence work at API Chaya and is part of the founding collective of Queer the Land. They believe that our bodies are sites of resistance– as workers, womxn, queers, indigenous people, artists, etc. and we must produce art, media and culture that not only reflect our daily struggles but also create the world we want to see.

Here’s How Queer and Trans People of Color Are Resisting Gentrification and Displacement

feature image is of Evana Enabulele

As I walk the streets adorned with rainbow crosswalks in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood, I shake my head at the irony of a “gayborhood” where housing is too expensive for queer and trans people of color. Here in Seattle, I watch the endless cycle of gentrification and displacement in communities of color as the practices of unscrupulous tech companies and real estate developers drive up rents to some of the highest in the world. Housing conditions in Seattle are eerily similar to those in Oakland, a place shaped by Black liberation activism that’s rapidly morphing into Google’s playground. Both cities are incubators of QTPOC resistance against gentrification and displacement, a movement which I belong to as a member of a collective called Queer the Land that is working towards purchasing property in the Seattle area to house a community center and a transitional housing cooperative. Recently, I interviewed fellow QTPOC based in Seattle and Oakland who are reclaiming land while taking time to honor the Indigenous people to whom it belongs and the enslaved Black people who labored there. Our conversations led me to reflect on my own narrative of displacement and on how gentrification impacted the LGBTQ+ people of color who came before us.

I define displacement as an act of violence fueled by the spoils of capitalism and colonialism. My ancestors knew this type of violence intimately as captives shipped across the Atlantic from the West Coast of Africa to the Deep South. After cultivating land desecrated by the Trail of Tears as enslaved people and sharecroppers, they never reaped the 40 acres and a mule promised to them and other freedmen at the end of the Civil War. During the Great Migration, some of my family members joined millions of Blacks leaving the South for better economic opportunities up North, which resonates with me as someone who left Atlanta with my partner for the gentler economic climate of Seattle three years ago. Like many other people of color, my family has survived in the face of chronic displacement.

For more than a century, QTPOC have resisted displacement in U.S. cities by unapologetically claiming space for themselves. During the 1920s, Harlem served as a mecca for Black queer creators who sustained themselves via revolutionary art and rowdy rent parties. A Black lesbian named Ruth Ellis opened her Detroit home up on weekends as a safer space for Black queer and trans people in the mid-1900s. Trans women of color activists Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera operated the STAR House in the 1970s to shelter LGBTQ+ runaways in NYC, using money earned from doing sex work to fund their project. Creativity and resourcefulness have allowed QTPOC to establish sites of safety and resistance within cities that benefit from our cultural contributions and wage labor but neglect our needs as those who are most vulnerable to homelessness and interpersonal and state violence.

When Eri Oura, 31, looks out the window of their home at the 23rd Ave. Community Building in East Oakland, they have a front row seat to what happens when gentrification decimates historically oppressed communities.

“Gentrification in Oakland looks like homeless encampments in every nook and cranny that folks can occupy. There are several encampments near us, including one across the street,” Oura says.

Oura, a third-generation Japanese-American genderqueer person, says gentrification negatively impacts the mental health of many queer and trans people of color in their community. Surviving and meeting basic needs has become a tedious task for many of their peers. According to Causa Justa/Just Cause, a grassroots tenants’ rights group that organizes in the Bay area, Oakland lost almost half of its Black population between 1990 to 2011. It’s the fourth most expensive city in the country for renters and is located across the bay from San Francisco, which is the most expensive rental market in the world. Mirroring Seattle’s housing predicament, corporations, real estate developers, corrupt landlords, tech workers, local government and orchestrated acts of institutional racism in Oakland conspire together to displace people of color from their neighborhoods.

In a seller’s market like Oakland, most landlords sell their property to the highest bidder with little regard for their current tenants. So this January when the landlord of the 23rd Ave. Community Building, a people of color-led social justice center where Oura lives and works, told tenants the building would be placed on the market unless they put in a bid by May 1, tenants rallied to raise the necessary funds. Since 2003, the building has been anchored by a queer and trans people of color collective house and garden project called Sustaining Ourselves Locally (SOL). The building consists of residential units where collective members live and storefronts occupied by people of color-led organizations, including a community bike shop, a martial arts and self-defense studio and a maker/hacker space.