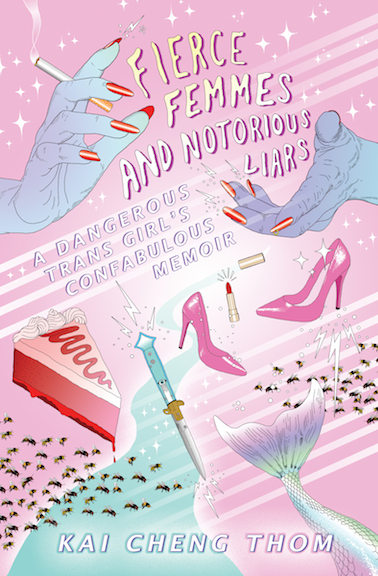

For Runaways, Survivors and Dreamers: “Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars”

Kai Cheng Thom’s Lambda-nominated debut novel, Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars: A Dangerous Trans Girl’s Confabulous Memoir, is a captivating tale of betrayal, murder, mysticism, legend and compassion. I devoured it within a few days and was terribly sad when I closed it, wishing that Thom could write a never-ending tale for every trans girl who needs more escapism, more vision and more badass resiliency.

That’s exactly what Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars creates — a magical place for every trans girl to insert herself into the story. A place where we belong. The beauty of this pseudo-memoir — which acts as a satirical commentary on the roots of trans literature as based in memoir — is that we get to identify with more than one character who’s canonically and unapologetically a trans woman, and not sensationally named as trans in every sentence, either.

For once, we get to insert ourselves as girl gang members, sisters, mothers, witches and goddesses. We get to be bald and sex workers and seamstresses and runaways and dancers and jealous friends. We get to be complex. We get to have a sisterhood of vengeance and victory. We get to be femmes who kiss and fuck one another, who fight back, who murder cops, who hurt each other, who fall in love, who survive tragedy, who forgive each other, who create homes together, who choose the kinds of lives we want to live.

As much as I loved reading Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars, it also hurt. Violence and danger are major themes, and Thom writes painfully realistic characters as able to hurt as they are to love. The main character falls into a self-fulfilling prophecy of thinking she’s just an abusive person, and therefore — often unintentionally, though sometimes purposefully — hurting those that are kindest to and most supportive of her. Like the pocketknife she carries that hurts her as she loves it, she is a blade that cuts those that she loves.

Most painful was the incorporation of trauma and tragedy in the femmes’ lives. Thom’s wildly imaginative narrative also includes legends of murder, death and violence in the lives of trans femmes. As much as I wanted this book to be fun escapism, the consistent violent reminders of what our real lives are like pinched me out of the surrealist fantasy.

But like our real lives, some of us survive to tell these challenging stories in creative ways that defy the systems and structures that enact violence onto us.

Over Skype, I asked Thom about memoir that isn’t memoir, the different sides of trauma, her literary choices and more in Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars. Note that there’s mild discussion of child sexual and physical abuse.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Luna Merbruja: I’ve been reading some of your interviews and promotional materials, and I’ve been finding that you’ve consistently said this is not an autobiography. [KTC laughs] There seems to be some confusion about that. How much of this was pulled from your experience? How much did you consult other people?

Kai Cheng Thom: The title itself is “a memoir,” but then it’s not a memoir.

The most honest answer I can give is that there are surrealist and magical realist elements, and then there are heightened elements. I’ve never [laughs] accidentally killed a cop, or if I had I would have to say I hadn’t to keep my plausible deniability or whatever.

There’s an amazing line in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire by Blanche Dubois, who is this terrible, aging Southern belle type. She’s lied to everyone in her life and then her boyfriend is like, “Why are you such a liar?” And she goes, “I never lied in my heart.”

The narrator’s emotional experiences [in Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars] are ones that I’ve all lived and experienced. The facts, or the details of the narrative, are heightened, surrealized and embroidered upon. Some of them are drawn from my life, but then brought into this mystical place.

In terms of the other characters, they each have a piece of me. As any author, I brought my own perspective to each of those characters. Most of them started off based on real life trans women, and then, much like the narrator, the details of their life stories, their appearances, or their personality have been heightened and mythologized to evoke a story that has a real feeling. Also, it plays with this idea of fiction being able to express truth better than fact.

LM: Early on in the book, there’s this character named Ghost Friend.

KCT: Yeeeeah! [Laughs]

LM: I had a hard time pinpointing what Ghost Friend was supposed to represent or be a metaphor for.

KCT: I love that you picked up on Ghost Friend. Most people ignore Ghost Friend or skip over them, but they’re super important to me! Ghost Friend is the flip side of trauma. We have the killer bees that are inside the protagonist’s body. They’re the sort of dark side or painful side of trauma, the part that keeps her from connecting to other people, the part that causes her to punish herself, all this kind of wicked stuff.

Ghost Friend is also a result of trauma, but the beautiful side. The side that allows her to connect with herself in particular ways. The side of her that really loves herself, that understands what she needs through the lens of trauma. In some ways it also brings her to close herself off to other kinds of intimacy, which is why when she’s finally opening herself up and being intimate with Josh at the end of the book, she has to give up Ghost Friend. Sometimes we need to give up parts of ourselves so we can receive from someone else.

LM: That’s helpful to conceptualize that Ghost Friend is in contrast to the killer bees. When I first read The Lessons of the Bees chapter, I definitely picked up on some child sexual assault undertones, which, may or may not be it. For me, it was really obvious, and throughout the book it kept coming up and feeling like triggers and traumas from that early experience. Is that an intentional choice, or, what type of trauma, if any, were you trying to create with the killer bees?

KCT: You know what’s interesting? Another trans woman reviewer brought up the killer bees and said she wasn’t sure if the killer bees were a metaphor for sexual assault, or for body dysphoria. Then she didn’t ask the question so I never had to answer it.

To get real for a second, I experienced a lot of trauma in childhood as many trans women of color do. I can remember moments of physical abuse and verbal abuse. I have a whole bunch of symptoms of sexual abuse also, but the actual event of sexual abuse — like the incident of it — I can’t remember.

Throughout my life, this is something that has been haunting. Kind of like, “Why do I have this reaction?” or, “Why didn’t people tell me that this thing happened when I have zero memory of it?” I know that it happened because of the way the story is told to me, but I don’t have an image or sensory memory or physical memory to substantiate that.

This is what lies at the heart of this concept of lying being able to express the truth. Me explaining sexual assault or my experiences of abuse to people, and not having the memory and being called a liar — those two things [end up] being tied together.

The idea of writing a memoir that had [the bees] at its heart, I and the protagonist didn’t have to stick to the facts. In this sort of cold, bullet point way, like, “This is what happened. This is what I remember, and this is something that can stand up in court.”

Because sometimes the reality of what is in our bodies just is. We shouldn’t have to prove it. That’s what those bees are for me, this powerful embodied experience without memory, without story — given a story of its own, and given an image of its own.

LM: I know I’m hitting in the heart with these questions [laughs].

KCT: Yeah! It’s so good, so good.

LM: This book challenges the memoir genre, and especially how trans memoirs are always saturated in trauma and focus on a cis audience. How did you decide what trans women characters to portray? At one point Kimaya talks to the protagonist about being “fishy,” and it seems like there’s a dichotomy between “fishy” being equated with success and the “not fishy” girls being disgraceful.

Can you also talk about the choices you made to portray trans women characters as being on the street doing different types of sex work?

KCT: Yeah, they’re all doing various types of sex work, some very different from others. I love that question and I’m really glad you asked it because I think a lot of cis reviewers or interviewers have shied away from this question. [Both laugh]

This is super real and a super important dimension of accountability around the novel as well. I’ve been wondering about it, particularly now. Why did I choose to represent the trans women that I did? Why is my protagonist the kind of trans woman who is named fishy?

Primarily, I wanted to represent a diversity of trans women, a diversity of trans women of color, and trans women who felt real. I knew that the only way I could do that was to draw from my relationships with real trans women and then fictionalize.

One of the relationship dynamics that has been really present in my life, in various ways, is this concept of fishy or not. And experiencing my own jealousy towards other trans women that I feel are more passable than me, or more successful in terms of capitalist types of success. Then of course, experiencing this other side of the jealousy of others toward me, because I have been really successful in terms of moving through the non-profit world and becoming a psychotherapist. This is a rare thing, and it has a lot to do with my privilege as a light-skinned, East Asian trans woman of color who went to university.

Grappling with that, and the disparity in relationships and the animosity and the jealousy and the sadness and the guilt that can come up, is really important. In terms of who the protagonist is, that conversation where the protagonist is named as fishy by Kimaya is an example of several of those conversations that have happened in my own life.

I wanted to represent [fishy] in a way that wasn’t, “Oh poor me, I’m so fishy!” There also wasn’t pitying of people who were less passable than I am, and also owning up to the fact that I’m not passable all the time.

LM: What feels important to you to share right now?

KCT: I see Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars as a huge ongoing conversation that’s just starting to happen between trans women, and particularly trans women of color, who are storytellers of any kind. The trans lit movement is white-dominated sometimes, and shuts us out. Now we have these amazing books by people like you (author of Heal Your Love), and also jia qing wilson-yang who wrote Small Beauty, and Gwen Benaway, and Jennifer Joshua Espinoza, and I think we all have complicated feelings about each other but also love each other.

I want to emphasize that I see this book as a collection of stories other people are putting out as well as me. I would never want it to be understood as the trans-woman-book-to-end-all-trans-women’s-books, or the most important book, or in competition. I think it’s such a flawed book in so many ways, I think I’m probably going to hate it ten years from now when I’m like, “Ugh, why did I think those things!”

To sum up, I’m grateful and humbled by the fact that you read this book and you liked it, and I’m really grateful and humbled at the fact that other people are reading this book. I encourage folks to go out there and read and support other trans women of color writers. Let’s all kick butt together.

Queer Latinx Love is Resistance: A Collection of Vignettes

feature image by Raquel Breternitz

Welcome to Autostraddle’s queer Latinx essay series: Our Pulse. In honor of celebrating Latinxs during Hispanic Heritage Month, Autostraddle curated a collection of essays by lesbian, bisexual, queer and trans Latina and Latinx writers to showcase our experiences, our pulse.

Our love can be beautiful and dramatic like telenovelas. Our love is inherently sacred by unlearning the toxic ideas of who and what is desirable, though sometimes internalized oppression can still plague our relationships. It wouldn’t be authentic to portray the glory of our love without the bitter tastes as well.

Latinx love in times of crises and revolution is resistance. I love that our love grows with pain into beauty, like thorny rositas in their natural state.

Here’s a bouquet of love notes to old and recent loves.

i.

It was my first quarter at university. I found you on Grindr, or maybe Adam4Adam. I’m pretty sure I subtly begged you to fuck me, and I’m pretty sure I believed you would be nicer than you were. I craved your attractive, beautiful, round face. Validation that an ugly creature like me could be adored by something as precious as you. Your brown dominated mine. Not a piece of you felt or sounded like home. I found solace when you left and I began to love myself, and you, for being hurt in different ways that led us to this regretful moment. I hope we find better love and lovers.

ii.

You were the first organizer to leave class with me because I was having a panic attack. You came to my dorm and held me in my twin bed because I asked for what I needed. You saw something hurt and something beautiful in me. I saw your hands and spirit as healing ancestral magic. Memory that somewhere along our lineages, we loved each other. You had familiar full lips, that brown pink that is nameless in color but unforgettable in sight. Long dark hair, dark eyes, face kissed by beauty marks. Our bodies similar in texture, smooth in many places, soft fur in the few crevices it did grow. How I loved touching you, being enveloped in home. Sleeping with you felt like being baked into fresh pan dulce. Coming with you felt like abuelita chocolate dripping down my body, pouring into your mouth. How delicious those two short weeks were. How savory I hold this memory.

iii.

Something about your ugly brought out my own. We summoned our demons and watched them play with each other, sinking venomous fangs into each other’s flesh to see who would paralyze first and quit this evil. Neither of us did. We were uglies who desired white beauties. Settled for each other, upset with each other, hurting each other, using each other. What did we walk away with? The scum of the river, foggy car windows, poems we didn’t read to each other, tasteless jokes, clothes drenched in pool water, and a sour taste of cum.

iv.

During my second puberty, dating you felt like high school. Wrapping blunts in your race car, listening to The Weeknd, playing Five Nights at Freddy’s, making out, you always inching your hand up my skirt to feel my throbbing dick, me always grabbing you by the back of the neck for deeper kisses. Interrupted by your parent’s phone calls, hearing you tell them “Estoy con mi amiga” at night but becoming amigo by early morning. The times you called me princesa, chula, then slipped up with the occasional chulo. It hurt on a children-and-grandchildren-of-Mexican-immigrants level, where that -o and -a are significantly more affirming than English can be. Yet, I appreciate you for those late nights you brought me In-N-Out and demonstrated your DJ skills. I love that we shared intimacy in brown Caló queer languages, that you made me feel young and silly, that you grew into someone better than who you were before me.

v.

Girl, you make me hate my memory loss when it often serves as a protective shield. There’s nothing more I want to remember than every moment and sensation we shared. Our grinding hips at Queer Cumbia, feeling your drunken sweat drip onto my freshly implanted tits. The way we sloppily made out and smeared our red and burgundy lips all over our mouths, noses, forehead, and neck. Maneuvering into the club bathroom, laughing as we used a half dozen wet paper towels to clean ourselves, taking selfies for the #tbt, for the story, for the hotness of Mexi trans girls sexually into one another. Grinding and making out with your partner, sandwiching and being sandwiched between Black and brown sexual intensity with anticipating fingers, tongues, hips, and erections. All of us in bed together, whispering, sharing stories, boundaries, and STI & HIV status. Fucking so good without any of the penetration, feeling in love with my body in all its hairy trans glory, in love with all the smells of lust and spit, hearing mami and baby and more and fuck yes and please and stop and that was so fucking good. ‘Cuz it was, really fucking good.

vi.

Our love was the definition of what-the-f*ck, but you’re just a Scorpio and I’m just an empath who can feel right through your bullshit. I know you love me, and I wasn’t afraid to tell you that I wanted to build love with you. There was room for our learning, together. Yet I was caught in that bind as I am with most men, knowing your good, gentle-natured heart is deterred by machismo bullshit of what you should do. To be fair, you wanted something slow and I wanted something sure. I wasn’t sure cis people could genuinely love me like they would a cis woman, though now I’ve learned that it doesn’t matter if I know that answer. Love is flexible and ever-changing, like us, from romance to hot sex to indifference. I am grateful for what we learned, knowing that I won’t be repeating you or relationships like ours.

vii.

I couldn’t date you three years ago when I didn’t love trans women, but I gave it a shot this year when I knew I could. Being with you was a reprieve from the onslaught of internalized baggage I learned to carry. Being with you taught me to be present in my body, how to cherish silence as bonding when the person you’re with is breathing in sync with you. I won’t forget you icing my sore chichis or rubbing that calendula and beeswax salve onto my incision scars, then offering to give me head when I couldn’t even sit up on my own. How you treated me and my body as a blessing, unveiling mirrors that allowed me to love myself deeper. You healed me in body and love, though in our relationship I mostly took from you, felt like I was fracking your resources until I depleted us. I broke up with you because I wasn’t ready to grow. Now in our friendship, I want to give you all the love I couldn’t when romance blurred me from seeing what a true lover you were.

So You Can Fuck Us; What’s Next? Going Beyond Sex With Trans Women

I’m writing this article centering experiences of trans women of color, though other trans women may relate as well. I’m discussing our disposability, lack of desirability, and offering strategies to combat transmisogyny within our communities. I speak on behalf of myself, the experiences I’ve collected, and possible solutions. What’s stated here may not be true of every trans woman’s experience, and this isn’t an article that is asexual inclusive since I do not have experience or knowledge with those experiences.

As part of Trans Awareness Week, I think it’s incredibly important to talk about dating and having sex with trans women. We have a legacy of being queer that is often erased in narratives about trans womanhood, and this article aims to bring that up while also pushing this discussion further than just having sex with us.

I read this incredible article about having sex with trans women, and there’s also a pretty comprehensive zine called Fucking Trans Women that I would recommend though I have only skimmed it. After seeing both of these exhaustive resources on how to gender a trans woman’s body and how to have sex with her, I began thinking of how people already only value us for sex. It’s definitely important to have great affirming sex and less awkward or awful moments, and I want to push this conversation forward about loving trans women beyond sex.

Abbygail Wu and her wife Wu Zhiyi

via whatsonxiamen.com

It’s within my experience, and the experience of at least a dozen trans women of color that I know, that we are the first to be disposed of in intimate relationships. By “disposed of,” I mean when life gets hectic for our partner(s), we are the ones who take the least priority and are the first “stressor” to be cut off. This is definitely an acceptable thing to do when someone is genuinely having their life fall apart and cannot maintain a relationship, so I am not advocating that every person stay in a relationship with a trans woman in every situation. I’m simply noting a theme that has been true for me and many trans women I’ve talked to about intimate relationships. I mean, what reason could you have for breaking up with us but maintaining a relationship (sexual, romantic, or a mixture of both) with other people? If your life is in shambles, wouldn’t it make sense to not be with anyone? Why are trans women the first to be cut off, and the only people to be cut off?

I feel like the answer of “transmisogyny” doesn’t explain enough. It’s because we are not valued as lovers, partners, or long-term relationships. The recent cultural trend of supporting trans women has made us highly prized assets; somehow you can prove your radicalness by being the example of someone who has worked through transmisogyny enough to view us as worthy of sex and love. But what kind of love views us as disposable? What kind of love makes us the casual fuck buddy while you pursue romantic interests with non-trans women?

Russian couple Irina Shumilova and Alyona Fursova

via instinctmagazine.com

There are other patterns I noticed with trans women of color, and I’m gonna break these down a little bit, depending on how complex I want to get with them:

When we are in poly relationships, we get the least amount of time and/or emotional investment.

I’ve seen and experienced trans women being the least prioritized in poly relationships. Again, because we aren’t seen as valuable of long-term relationships or emotional investment, we are treated like sex experiments for Radical Points without being centered in another’s life. I’ve had a few conversations where TWOC admitted that they didn’t want to be in poly relationships, but didn’t think anyone would seriously commit to being monogamous with them. This has led to flexing our boundaries in order to have some semblance of love in our lives rather than nothing.

We are left or cheated on for lighter-skinned/white trans masculine people.

It is seriously a community trauma. Almost every queer trans woman I know has experienced being devalued for someone lighter-skinned or white, and/or masculine. This is probably one of the worst damages done to a TWOC because it has led to lots of feelings of self-loathing and questioning of self-worth. We are constantly resisting white supremacy. We are viewed as the opposite of cis white men, and to be left for a cis white man can lead to feelings of inadequacy and undesirability. Especially in situations where we are cheated on for white masculine folks, that deception and betrayal cuts deep into self-esteem because the message is “a white masculine person is worth the ending of our relationship.”

Sofia Burset and her wife, Crystal from Orange is the New Black

We are often the “first” for someone, regardless if they’re straight or queer.

Being The First for someone, regardless if they’re queer or straight, is one hell of a roller coaster. Since there’s so many narratives of trans women being loved in secrecy, it’s terrifying to be out in public with a First Timer since we are viewed as “giving them away.” I’ve tried to shrink myself, talk less, and become hypersensitive of my body instead of feeling present. As the article “Trans Women + Sex = Awesome” states, if you’re going to be with a trans woman for the first time, process that shit with your friends or therapist or family first before you place that responsibility onto us.

We bear the weight of stigma for our partners being attracted to us and being seen with us in public.

Related to my last point, we bear the stigma any person faces for dating us, especially straight cis men. Since cis men’s straightness is called into question for being with a trans woman, this can lead to a lot of issues with intimacy. We become the scapegoat, which can leave us susceptible to violence (Janet Mock writes about this here). We become the reason that cis men’s sexuality is invalidated. It takes a lot for cis men to own up to their desires towards us, especially when it involves sex *and* romance beyond bedroom dates. The best way for anyone to approach their attraction to trans women is being fiercely unapologetic about it to your social circles, and exposing us to as little of the lash back as possible.

Additionally, lesbians also face stigma for dating us because we aren’t seen as “real women.” This transmisogyny has been persistent in many lesbian communities because a strong basis for their identity is not having sex with a penis, which makes the assumption that all trans women have penises or want to use their penis in sex. Many lesbian or queer women’s spaces have made space for trans men but not for trans women. I encourage cis lesbians to talk to each other about why this is, to undo their transmisogyny of viewing penises as revolting, and de-centering the idea that being a lesbian requires an aversion to penis or that lesbians cannot be in relationships with women who have penises.

We don’t get asked out on dates in queer spaces, and there’s a lack of sexual tension that many other queers share with each other.

This is real. In my 3+ years in queer spaces as a trans woman, I haven’t been asked out on a date. Most TWOC I know haven’t been asked out on dates by other queers. This often leaves us to dating straight men who do initiate contact with us, or we have to pursue romantic/sexual interests ourselves.

This notion that trans women are only straight stems from outdated medical guidelines around gender identity that created the idea that to be a “legitimate” woman meant being heterosexual. Trans women have a legacy of being queer, including Sylvia Rivera and her partner Julia Murray. Fallon Fox, an MMA fighter, is also in a relationship with a woman and I, too, am centered on dating, loving, and desiring femmes and women. Queer/lesbian trans women exist, and we’re worthy of the risk of being asked out just like every other queer.

We are viewed as supporting patriarchy by dating straight cis men.

Honestly, in my experience, I have found cis straight men who have handled and viewed me as a woman more readily and steadfast than cis queers. It is incredibly validating having cis straight men view you as a woman worthy of desire and love. I have had transformative sex with cis men who have unapologetically embraced my body in ways that countless queers have not. There’s been this hesitancy with queers who are afraid of my body, or who have not worked through their transmisogyny that makes them disgusted by my body. I know the focus of this article is on love, and when sex is tainted by disgust, that prevents folks from Making Love to us. By saying we are supporting patriarchy by being in relationships with cis men, you are denying us healthy, supportive, and loving relationships. And you can go fuck yourself for that.

Sylvia Rivera and her partner Julia Murray with Randy Wicker.

Photos by Randy Wicker & Diane Daives

…and also, I dream of finding a femme or woman who has dated trans women before. As much as cis straight men are accessible to me now, my sexuality and desires are still centered on finding love and partnership with a femme or woman.

*Inhale of a deep breath*

*Exhale of a deep breath*

My goal in talking about these patterns was to make other aware of what trans women have to deal with when dating. I mean, there are simple things like Don’t Lie To Your Partner(s) that every person should know, but can always use some repeating because it’s still a problem. If you see yourself doing any of these things (putting the burden of being a First Timer on your trans woman partner, desiring whiteness and/or masculinity over your trans woman partner, giving trans women the least amount of your resources/time/intimacy, etc), seriously ask yourself why you’re being such an asshole and talk about it with people who aren’t your trans woman partner.

I know we’re magical and powerful and amazing and magnificent and can handle tons of shit, but maybe try to make our lives easier and enjoyable and relaxing instead? That’d be nice.

November 14th-20th is Trans Awareness Week, leading up to Trans Day of Remembrance on the 20th. This is a week where we raise visibility for trans people and address issues that affect the trans community. For Trans Awareness Week this year, we’ve asked several of our favorite TWoC writers to come in and share their thoughts and experiences with us. TWoC started the entire LGBTQ movement in the U.S. And they continue to be the victims of most of the anti-LGBTQ violence and discrimination. If we aren’t centering things on them, we are failing.