Principles of Pride: Sex Work Is Real Work, Sex Workers Are Fucking Revolutionary

As part of our No Justice, No Pride programming, our trans subject editor Xoai Pham has curated a five-part series called the Principles of Pride. The series unpacks the foundational values that clear a path forward for the LGBTQ movement, values that would make our ancestors proud. This is the second in this series; you can read the first here: Police and Prisons Do Not Belong in Our Future.

Let me tell you something about sex work: It saves lives. Sex workers, more often than not, are people who have saved their own lives by seizing control of the most important means of production; that is, our own bodies.

Let me tell you something about me: Sex work saved my life when I was suicidal and broke… Sex work gave me a livelihood and autonomy, when chronic illness and transphobia meant I couldn’t make a living otherwise. Sex workers taught me resilience and self-worth. Queer “community,” with its endless callouts and purity politics, has never come close to doing that. Meanwhile dominant society marked my racialized trans woman’s body for death a long time ago. Sex work saved me when nothing else would, gave me a way to save myself.

Maybe you came here expecting a congenial, well-reasoned article patiently defending the virtues of sex work as a profession and politely asking for solidarity. This isn’t that article. That article has already been written, several times, by several different authors. That article should have changed all of your minds already about the fact that sex workers are human beings who deserve basic human rights, but apparently it didn’t, so here we are. Still criminalized, still stigmatized, still by and large ignored by mainstream “LGBT community,” despite the fact that transfeminine sex workers such as Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera are the reason that we have Pride in the first place.

People love the idea that sex workers need saving. A lot of money, power, and attention goes into that idea – not to sex workers, but to our would-be saviors: Non-profit organizations, psychologists and social workers, sex work exclusionary “feminist” activists, and the police. Perhaps this is why the sex worker salvation industry has yet to even try to change any of the socioeconomic conditions that lead to the exploitation and endangerment of sex workers in the first place: Poverty, primarily. Housing and employment discrimination. Incarceration. Domestic and familial abuse. In order to do that, though, anti-sex work activists and police would have to actually care about sex workers’ actual lives, as opposed to their self-image as Real Life Heroes™ rescuing us from evil human traffickers.

Human trafficking is a real concern that must be addressed and brought to an end. Note, however, that human trafficking – the bondage and forced labour of human beings – is not unique to the sex industry, but rather endemic to capitalism. Human trafficking occurs in the fields of domestic labour, agricultural work, and other low-status occupations as well as sex work, and will continue to occur for as long as we live in a society that values economic production over the rights and freedoms of workers. Note that the criminalization of sex work (not to mention undocumented migrants) actively prevents many victims of human trafficking from seeking help.

Oh, and in case anyone was wondering? Human traffickers target members of vulnerable groups, such as queer and trans youth, racialized women, and migrants, not middle-class white women in shopping mall parking lots, viral social media memes notwithstanding.

Many of the sex workers I know are brave, resilient survivors who turned to sexual labour in order to get out of a bad situation – commonly referred to as survival sex work. Yet many others are badass hustlers carving out a lucrative livelihood in the midst of a rotting capitalist system. Still others are erotic muses, artists, and healers who have found their true calling. There are an infinite number of ways to be a sex worker, but we have one thing in common: We deserve to determine our own paths and tell our own stories, just like everybody else. That’s why sex work must be fully decriminalized immediately, and preferably sooner.

Artwork by Féi Hernandez. You can follow them at @feihernandez on Twitter and @fei.hernandez on Instagram.

Criminalization punishes and kills sex workers: For one thing, it drives our work underground, leaving us susceptible to violence and exploitation from clients and employers. Worse, it also opens us to vast amounts of abuse by law enforcement, who are allowed to detain, humiliate, and assault sex workers with virtual impunity. The criminalization of sex work primarily targets, and most significantly affects migrant, poor, queer, and trans people of color—and especially Black and Indigenous people. Is it any wonder that the vast majority of sex workers are in support of recent calls to defund and abolish the police?

Even the much-vaunted “Nordic Model,” which purports to protect sex workers while criminalizing clients, is actually extremely harmful. This is because it makes clients unwilling to provide essential screening information (for example, their legal names and employers) that can help to keep sex workers safe. The Nordic Model also significantly reduces the market for sex work – which might sound good to certain radical feminists in theory, but in real life results in sex workers being less able to turn down unsafe or exploitative working conditions.

Sex workers are not a thought experiment. Masturbatory left-wing intellectual debate about “whether sex work would exist in a post-revolution society” is not only irrelevant to our actual lives, but condescending and inherently sex-negative. So-called progressives, sex work-exclusionary feminists, and conservatives all seem to imagine our lives as a bottomless fountain of tears, days spent weeping with our feet in the air as an endless horde of degenerates pummels us relentlessly from above.

What if I told you that sex workers are brilliant strategists, seasoned businesspeople, technological innovators, and skilled professionals? Sex workers were among the first to innovate internet advertising, as well as social media marketing – innovations that were promptly seized upon by entrepreneurs of all kinds. Sex workers’ expert knowledge of human eroticism and intimacy were used by world-renowned sexologists, Masters and Johnson, to develop what would eventually become contemporary sex therapy. The influence and accomplishments of sex workers are everywhere, if you only you bother to look.

What if I told you that our job, at its heart, is about giving people pleasure, which is a vastly more ethical and worthwhile pursuit than most of the high-status professions in existence today? Why do we try to debate and legislate sex workers out of existence while hedge fund managers and corporate lawyers walk about in broad daylight?

No, not every sex worker is in the business because they enjoy the work. Do Amazon warehouse employees and fast-food service workers all love their jobs? Do nurses and doctors, now that the COVID-19 pandemic is here? Sex workers are the target of an extreme double standard that says if we aren’t screaming with joy every second of every day, our work isn’t legitimate. What, exactly, makes a job “legitimate”? What makes a worker worthy of respect?

If you don’t stand with sex workers, you’re not a real progressive, feminist, or queer activist. If you’re not paying attention to and learning from the wisdom, experience, and genius of sex workers, then your politics are missing something essential that can’t be found anywhere else. Do you want to support sex workers? I have some suggestions: Stop trying to “save” us. Start connecting with sex work support organizations that are run by sex workers. Call or write your political representatives and demand the immediate decriminalization of erotic labour. And for the love of god, stop judging and shaming people who pay consenting adults for sex – or better yet, consider hiring a sex worker yourself (remember to tip well).

Sex workers have a vantage point on society, policy, and community that no one else does. Sex work history has a deep, rich legacy of advocacy, mutual aid, and protest – of holding and fighting for people that have been otherwise forgotten. Marsha P Johnson and Sylvia Rivera started the first home for homeless queer youth. A sex worker named Mirha Soleil-Ross started the first social service program for trans people in Canada.

Imagine, if you will, a world in which sex workers were free – not just safe, but really free, as labourers and as human beings. Sexual consent and healthy intimacy would need to be woven deep into the culture of such a world. In a world where sex workers were free, the rights of workers, people of colour, women, and trans people would need to be centred and nurtured in the collective consciousness. Body positivity and body sovereignty, including the right to reproductive and gender transition healthcare would have to be a given. A free world for sex workers would be a free world for people’s bodies, desires, and pleasures – that is to say, a world worth fighting for.

Tell me, what’s more revolutionary than that?

Organizing A Sex Work COVID-19 Relief Fund Restored My Faith In Community

Graphic by Sarah Sarwar

When COVID-19 hit North America, I had pretty much given up on community organizing: More than ten years of witnessing transmisogyny, explosive conflict, vicious call-out culture, and burnout in activism had jaded me to the romance of “the revolution.” An activist since my late teens, I was pretty sure I was done forever with being an organizer.

Then the pandemic arrived and threw everything into pandemonium. Dreams were crushed and plans fell to dust. The socioeconomic devastation of the pandemic has affected literally everyone, but perhaps no community more than the one dearest to my heart: sex workers.

Like many trans women, my life has been intertwined with the sex industry from a young age. Sex workers supported me when I had no one else, taught me how to protect and value myself, gave me survival tools to navigate a transphobic world. As someone who has been a counselor, community organizer, and artist, let me tell you something: No one knows resilience, resistance, and creativity like sex workers. No one does care and love like sex workers.

So when the pandemic arrived, instantly pulling the plug on a vast swath of sex workers’ livelihoods, I let go of my misgivings about organizing and threw myself into a relief fund project with Maggie’s Toronto Sex Workers’ Action Project and Butterfly Migrant & Asian Sex Workers Support Network, two sex worker support orgs in my home city. Our goal was simple: Raise $10,000 and put it into the hands of the most marginalized sex workers.

Sex workers are a vulnerable population: Criminalization and stigma create a context in which erotic laborers – especially queer and trans, racialized, and poor individuals – can be abused and exploited. In the pandemic, these same barriers block many sex workers from accessing the government relief that so many people are now relying on.

“The criminalization of sex work creates barriers to applying for relief. Many workers don’t feel safe providing employment information. For some this means not filing their taxes, resulting in ineligibility,” says Jenny Duffy, Board Chair of Maggie’s. Migrant sex workers face further challenges, such as the threat of deportation and language barriers – my colleague and friend Elene Lam, Butterfly Director, adds that many migrant sex workers are not able to access any emergency support and are struggling to pay for essentials like rent and food.

I wasn’t sure what to expect when I joined the team – like many of us trying to get through the pandemic, I only knew I had to do something. Would “the community” even care about what we were trying to do? Did anyone care about sex workers, when the chips were down? My jaded activist heart didn’t hold a lot of hope.

Imagine my surprise when the donations started rolling in – and kept on rolling. To date, we’ve gone from our goal of $10,00 to raising almost $100,000, and we don’t plan to stop now. Our small team of fundraisers has drawn on all the street-smarts and creativity of the sex worker community to get the word out and bring that coin in: We’ve used tactics from personalized donor calls to a social media influencer campaign to networking with wealthy philanthropists.

People are coming together around this thing we’re doing – and so many other mutual aid projects – and it’s more powerful and vibrant than almost anything I’d experienced in a decade of activism.

As for my jaded, burnt-out, done-forever heart? We’ll see. We’ve still got a lot of pandemic left to go. But it might be starting to soften, just a little.

Donate to the Butterfly and Maggie’s Sex Worker Relief fund: https://www.maggiesto.org/covid19

COMMUNITY CHECK is a series about mutual aid and taking care of each other in the time of coronavirus.

A Better World: Transformative Justice and the Apocalypse

We are living in the dying ruins of a world built by colonization and capitalism: Never has this been more apparent than now, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is forcing us to re-evaluate every aspect of our personal and political lives, and revealing the vast inequities built into capitalist society: Who gets to work from home? Who has access to paid sick leave and healthcare? Who has to work outside, to pay rent without any prospect of income; who among the vulnerable will be scapegoated, exploited, deemed expendable and left to die?

Even more dangerous than the virus itself is the danger of human cravenness, human greed, the impact of “everyone for himself” thinking that dehumanizes the other and corrodes the bonds of collective thinking and community care. More than ever, as world governments fail those of us who are queer and trans, poor and disabled, Black and Indigenous and racialized, we will be forced to rely on each other in order to survive and give pleasure and meaning to our increasingly dangerous, chaotic lives. In order to do so, we will need to find our individual and collective integrity. We will need to create strong webs of care that are resilient and accountable that leave out no one, that dispose of no one.

We will need transformative justice: The principle that we must transform the social conditions that allow the harm, exploitation, and disposal of human beings (some would say all beings), into better ones.

![]()

Last fall, I released a book titled I Hope We Choose Love: A Trans Girl’s Notes From the End of the World, a title that seems weirdly prescient now – as does the title of my biweekly advice column, Ask Kai: Advice for the Apocalypse. In truth, I’ve been waiting for the end of the world for a long a time. Both the book and the column centre around two fundamental themes: How do we love each other, and ourselves, even through enormous violence and pain? And how can we change ourselves, and the world, based on an ethics and politics of love?

These questions are, for me, firmly rooted in the philosophy of transformative justice; and I believe that they are massively important questions in the face of a collapsing world order. The massive crisis of COVID-19 has made these questions all the more urgent, because in times of crisis, both the best and worst extremes of humanity emerge and make themselves known.

We are seeing the worst already in the racist backlash towards East Asians here in North America, and in the hoarding of vital resources such as food and sanitation products. In declaring states of emergency, various governments are empowering themselves to enforce life-saving social distance and quarantine measures, but I fear they are also likely to abuse those powers to the detriment of marginalized groups. Migrants, sex workers, and the poor in particular are already seeing their incomes lost, their labour exploited, and their movements restricted where the wealthy and powerful are no

Yet COVID-19 is also forcing many parts of the global regime to embrace measures that the political left recently only dreamed of: Eviction and mortgage freezes, various forms of increased social welfare, the release of tens of thousands of prison inmates. The virus is making manifest what those of us in transformative justice, prison abolition, and progressive movement building have always known:

The survival of the most vulnerable is crucial to the survival of us all. Even before the virus, the fact that some people are homeless while others have mansions, that some struggle to pay for food while others hoard billions, and that racialized people go to prison for minor infractions or nothing while wealthy whites get away with literal rape and murder with impunity, was unspeakably wrong.

All of these issues, and their solution, hinge around the way we see and organize our world: Are some people worth more than others? Are some people simply disposable, ie deserving of being thrown away? Capitalism says yes to both of those questions. Capitalism says, this is the way it has to be for us to survive as a species – and is currently being proven wrong by COVID-19. Transformative justice says no. Transformative justice says the survival of one is the survival of all.

![]()

All of the above is, of course, pretty abstract. How do we actually do transformative justice on a day to day basis, as marginalized people who are already struggling for basic resources? The answer to that is becoming increasingly complex in pandemic-stricken context, but I believe the beginning is rooted in how we treat ourselves and those closest to us. I believe it starts with rejecting the notion of punishment as our primary strategy for achieving justice.

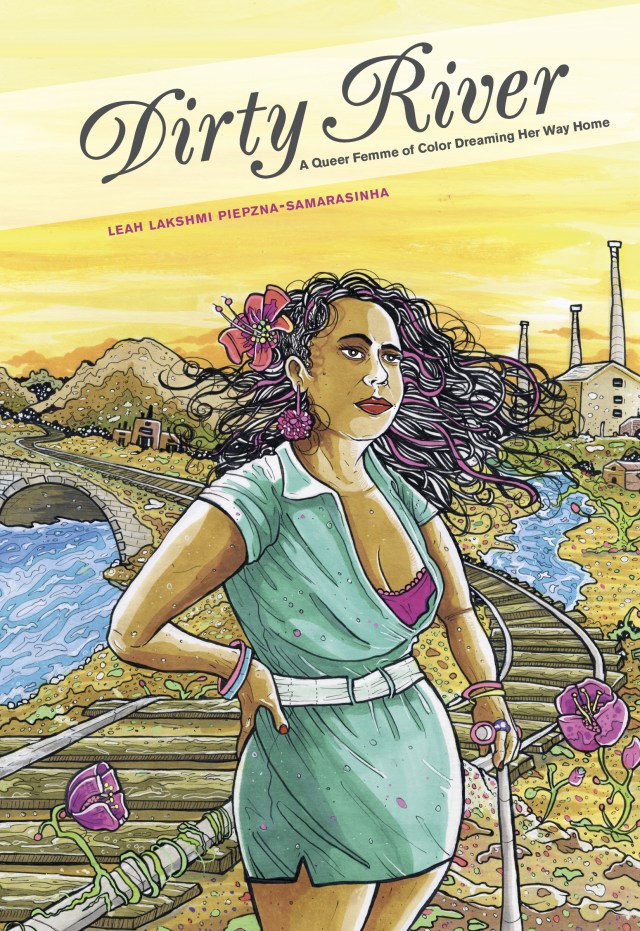

This idea is not new: Social justice writers such as adrienne maree brown, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, Mariame Kaba and Mia Mingus have been organizing and writing for years now about non-punitive ways of seeing the world and approaching social change-making. Yet it remains extremely challenging for most of us in social justice and queer communities (myself included), because the capitalist, colonial world we live in is centered around punishment as its greatest organizing principle.

Punishment – the fear of public shaming, violence, deprivation, incarceration, and death – is how European colonizers controlled Indigenous and enslaved populations. Punishment is how capitalist and authoritarian governments force individuals to submit to a worldview in which the only way to be seen as worthy of resources is to work for others, often for meagre wages in terrible conditions. Queer and trans people have been viciously, violently punished by straight, cisgender people for much of colonial history. Children are raised and educated through punishment in most schools. There is not a single aspect of our society that is not touched and shaped by punishment.

So it begins with a question: Can you imagine a world without punishment?

![]()

On my book tour for I Hope We Choose Love, which began in the Fall of 2019 ended shortly before the COVID-19 pandemic hit North America, I went to queer and social justice communities in cities all over Canada. Of all my books, this was the one I most hoped would have a real impact on people’s day to day lives, so I decided to turn each book launch event into a workshop, rather than a straight up reading. I always began the question: Can you imagine a world without punishment? What would it look like? Sound like? Smell like? How would your relationships be different or the same? How does your body feel in this world? Do you like it? Dislike it? Both at once?

This question tended to release a wide range of reactions in the people I asked: Numbness. Excitement. Fear. Anxiety. Hope. Frustration. Each of these responses is a valid one – after all, it’s a question about fundamentally reshaping the world we live in. Yet what I also found was that in every group, people were hungry for possibility, for a way out of the seemingly endless loop of transgression and punishment.

People wanted to know how to respond to abuse and harm in their communities without either sacrificing the needs of the survivors or completely cutting out perpetrators of harm. People wanted to who to believe when two people accused each other of being an abuser. People wanted to know how to respond, how to make amends, after being abusive. People wanted to know what to do when someone they loved had done something awful.

So many people who came to my readings and workshops had seen so much suffering, so much violence, so much bitterness. Punitive approaches – either calling the police and going through the criminal justice system or using “community accountability” approaches like shunning and ostracizing people had failed them. Punishment tends to fail. Trans video game maker Porpentine Charity Heartscape writes that this is because punishment is not really a balancing of the scales of justice, but rather a tool of the powerful. The vulnerable will always be punished, even when they have done nothing wrong. The powerful rarely will, even when they have done great evil.

![]()

Ever since I started to write about abuse and transformative justice a few years ago, I’ve received dozens of emails from people I don’t know. Some of the emails are thousands of words long, they are impassioned and often desperate. They are from people who have realized that they have done harm in their lives – sometimes awful harms, like sexual assault and psychological abuse. They want to know if it’s possible to be a good person again, after that. They want to know what transformative justice might look like for them.

Abuse is like a disease, a pandemic: It spreads and spreads. It is all over the globe. We receive violence, punishment, trauma; it enters our bodies and then we pass it on to others, at a rate so intense and insidious, it seems impossible to stop. The measures we take don’t seem to be working. The most marginalized are disproportionately impacted, but all of us are profoundly affected.

COVID-19 is changing our world forever: Even if capitalist society does, somehow, recover, it cannot and will not look the same as it did before. Certainly millions, if not billions, of individual lives will be completely changed. The trauma of abuse and other serious interpersonal harms is often similar. There might – might – be recovery. There is no going back. No amount of retribution can undo trauma, though it can certainly cause more.

Yet people cling to punishment, perhaps because it feels like there is nothing else to do in the wake of harm. We are conditioned to believe that we cannot ever be safe again without punishment. We confuse setting boundaries and defending ourselves with revenge.

Here, I think the pandemic in its evocation of extreme human behavior can provide us with some clarity. In the early days of North America’s plunge into social lockdown, we saw not only intense hoarding behavior, but also exploitative, predatory actions. Some individuals bought up enormous amounts of necessary supplies and resold them at a huge mark-up.

The immediate response of many people – myself included – was that individuals were despicable (indeed, perhaps they are). When I spoke to my friends about it, several said quite seriously they thought those people should be hung or beaten. I understand that impulse on a visceral level. But another response is that the community could (and in some cases, did) simply take back all of the resources that had been stolen and redistribute them equally. No extra harm necessary to fix the problem.

Transformative justice thinking can take us even further toward lasting, non-violent solutions. What leads to pandemic profiteering? Vulnerability and a capitalist dynamic in which money determines our access to essential resources. Yet if we lived – or created – a society in which having a lot of money did not give people the right to buy up huge amounts of things that everyone needs, then profiteering would be much less likely to happen in the first place.

If we created a culture in which sharing and ensuring each other’s collective survival resulted in greater social status and security than seizing goods and extorting people for them, then people would likely be less motivated to become robber barons.

The complex dynamics of abuse and intimate violence make them more difficult issues to imagine solutions for. Yet the basic philosophy of transformative justice still holds: We must ask, what leads to abuse and violence within marginalized communities? There are many answers, but a common one is that traumatized individuals often do not know how to get their physical and emotional needs met without resorting to manipulation or coercion. Such individuals then find more vulnerable people whom they are able to manipulate or coerce without consequence.

Transformative Justice in this area begins by changing the conditions that allow harm to continue – by taking away people’s power to harm and by giving survivors what they need to be safe. For example, so much abuse could be immediately stopped by ensuring everyone had a basic income and secure housing – because so many survivors are unable to leave abusers due to economic dependence.

The work does not stop here, though. We can continue it by addressing the factors that lead to it in the first place. We must create communities in which everyone can get their physical and emotional needs met, and we must create a culture in which everyone is nurtured and taught how to do so in a healthy way.

![]()

This philosophy of transformative justice can feel vague or “fluffy” because it takes so much time and emotional investment. It often seems much easier to revert to determining guilt and innocence and then assigning punishment – this, at least, is a concrete result. Then again, if as much money and brainpower were put into transformative justice as is put into the prison industrial complex, we’d likely have a lot more well-developed strategies and tools for it.

That said, it became clear to me as I went from city to city that the people I was meeting had already often thought deeply about the issues I was talking and writing about. What they were asking for was concrete strategies, specific ways to put Transformative Justice into action.

I believe that transformative justice is not like – cannot be like – colonial law, in which a rigid set of rules must be forcibly applied to every single situation. Transformative Justice as I know it comes out of communitarian organizing, anarchist and anti-authoritarian visioning, with connections to many different Indigenous lineages. It is a set of principles that must be applied fluidly and critically on a case-by-case basis, a way of feeling and connecting to others as well as a way of acting. In this way, it is more challenging than colonial law, because it requires greater integrity from all involved.

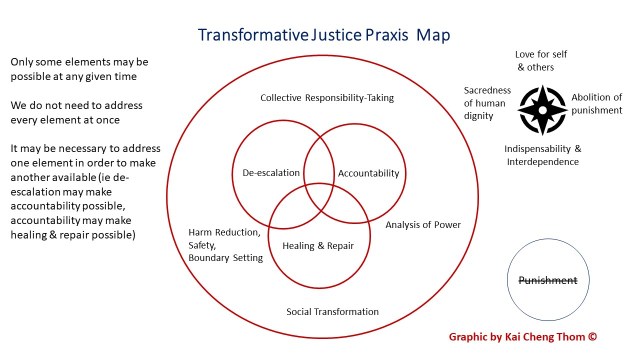

To guide my own thinking and practice of transformative justice as an individual, I made a map of the values and principles that guide me:

When I share this map, it is meant as inspiration, a map for the independent thinking of others, and not as a hard-and-fast set of rules. The compass in the corner of the map represents four values that I hold sacred – broad ideas that I return to when I am perplexed and overwhelmed by the situations before me. The three interlocking circles represent goals that may overlap but can also be pursued independently:

De-escalation: We can de-escalate harmful or violent situations without needing to assign guilt or retribution. De-escalation usually involves acting quickly and decisively in order to get people out of harm’s way – for example, getting people food and medical supplies if they are sick and alone, or separating two intimate partners who are being violent to each other in a shared home.

Accountability: Accountability involves the naming of harm and individual actions that are harmful. Ideally, people who have committed harm take responsibility for their own actions. For example, someone who has committed an assault may be confronted by the community and asked to undergo a process of self-reflection and restitution. The person who has done harm may be removed from positions of power that give them the ability to harm.

Healing & Repair: Healing and relationship repair involve addressing trauma and other psychological wounds of the survivors and the perpetrators of harm. This could involve therapy, ceremony or ritual, a process of amend-making, or other strategies.

These three goals may support one another, but they do not all have to be achieved at once, and they are not reliant on one another. As Mariame Kaba points out, it is a fundamental error to believe that accountability will result automatically in healing and repair – because sometimes healing is not possible. Sometimes accountability, too, is not possible. When one of the goals of transformative justice is not possible, we can still pursue the others. Where criminal justice relies on punishment in order to be deemed successful, transformative justice is measured by the increased safety and capacity of the community.

The larger circle that holds the three smaller ones represents the broader strategies that Transformative Justice can take, and that inform Transformative Justice actions: collective responsibility-taking, harm reduction and boundary-setting, analysis of power, and social transformation. These strategies look beyond the individual “perpetrator” and “survivor” framework to focus on the ways that the broader conditions of the community led to harm in the first place, and how each community member can shift their behavior in order to help prevent harm from happening again. For example, a community might raise funds to start an education campaign on healthy relationships and develop strategies for noticing and intervening in abuse.

Transformative Justice does not need to fixate on finding a perpetrator in order to be effective, and it seeks to reveal the ways that the dynamics of the collective impact individuals. We can see this too brought into stark relief by the pandemic: Some will search for people to blame, calling COVID-19 the “Chinese Virus,” and targeting Asians. But assigning guilt will not solve the problem. Only collective action – the work of individuals in social distancing, giving each other mutual aid, and engaging in sustained political organizing to ensure that vulnerable populations are protected, can help us all.

![]()

Transformative justice operates on the fundamental belief that we can do better, be better. It relies upon the capacity of human beings to find our better natures in the midst of extreme circumstances. This is part of the great challenge of transformative justice, because it is in fact very difficult to believe in the better nature of human beings in times of trouble. This is especially true of moments like the one we find ourselves in now, when great uncertainty has suddenly become the new normal and enormous tragedy seems all but inescapable.

When I wrote I Hope We Choose Love, I had just experienced three long years of devastating personal loss, and the world was in the throes of a climate crisis and the rise of a wave of right-wing, regressive political leaders. I had experienced extreme psychological abuse, chronic illness, and the loss of people who were very dear to me. I was witnessing my community fall apart (or so it seemed) in the face of what seemed like an interminable chain of call-outs, bullying, and “accountability processes” that never seemed to cause anything except more pain. My world had ended, but I refused to die. I often said, in that time, that I had hope but not faith, which is why I began to study transformative justice.

Now, here we are, at the end of world as we know it. Our politics, our organizing, our action, our relationships, are already transforming, changing in an infinite number of ways as a deadly virus descends upon us. There are no silver linings in tragedy, but there is potential in crisis. In the darkness, there is discovery.

I believe we can build a better world out of the one that is dying now. It will take great strength, courage, integrity, creativity. There will be loss. However, we have the tools and the capacity – the capacity to choose each other, to prioritize collective care-taking and courageous world-building over individual gratification and “getting back to normal.” Do I believe we will do this? I don’t know. I have hope, but not faith.

Yet I hold on to the knowledge that, in the weeks before our world ended, I had the privilege of traveling to many communities, of sharing my visions and my hopes. I remember the feeling in those rooms, in those circles of people as we closed our eyes and imagined what a better world might look like. I remember that intense, embodied desire – that yearning, born of pain, and carried by hope – for a different way of being.

Another world is possible. It might be almost here.🔮

Edited by Kamala

Surviving Utopia: Finding Hope in Larissa Lai’s Piercing Novel “The Tiger Flu”

There is no author whose words speak as precisely to the convoluted chambers of my queer, diasporic Chinese heart as speculative fiction writer Larissa Lai’s do: over a decade ago, I first picked up her novel Salt Fish Girl and fell into a painful, poetic world of ferocious beauty, meticulous worldbuilding, and piercing moral complexity.

Here, at last, in this vision of bioengineered women, time-travelling spirits, vastly overgrown capitalism, and clandestine resistance, I saw a piece of my angry, queer teenage self reflected. Here, at last, of all the Chinese writers whose work I had so hungrily pored over, was a feminist, queer, Chinese (Canadian) author who defied the tropes of the traditional “immigrant family story” so often assigned to racialized writers in North America yet still found a way to honour the lives and teachings of our ancestors.

It is particularly exciting, then – and a particular honor – to review Lai’s latest novel, The Tiger Flu, which is her first book-length fiction work to be published in sixteen years since the release of Salt Fish Girl. Lai’s work has something of a cult following among readers of queer and feminist speculative fiction. Her work has received extensive critical and scholarly attention; particularly in Canada, where her novels When Fox Is A Thousand and Salt Fish Girl have influenced a generation of queer spec fic writers and readers.

Yet she remains relatively niche in terms of public following, especially internationally, a shame considering the undeniable brilliance that shines through Lai’s prose. Both Salt Fish Girl, now nearly two decades post-publication and The Tiger Flu, released this fall, comprise sprawling visions of the future that have much to offer marginalized readers and communities in this time of rising global fascism and environmental disaster – not the least of which is a vision of hope.

“I don’t necessarily think of The Tiger Flu as a dystopia,” says Lai in an interview with Autostraddle for this review, “I know it has many dystopian elements– how could it not, given the state of the world. But it is a novel that is actively seeking possibilities for life […] This novel asks how it might come to pass that [the figure of] the girl child/ren survives.”

Life – fierce, painful, unyielding, complicated – bursts from every page of The Tiger Flu, which tells a story of love (and hate) between women in a futuristic world overrun by corporate technocracy and the effects of climate change. The novel’s two protagonists are Kora, a working-class girl from a poor family in the urban center of corporate power, Saltwater City (the name is a tribute to the Cantonese appellation Haam Sui Fauh, “salt water city,” used by early Chinese immigrants to describe Vancouver); and Kirilow, a healer from the exiled community of mutant women known as the Grist Sisters.

Brought together by a series of complex and tragic circumstances, Kirilow and Kora are forced to work together to ensure their own survival, as well as that of the ones they love, as sinister forces within the corporate ruling class conspire to exploit and ultimately destroy them. All the while, the mysterious and deadly epidemic known as the Tiger Flu ravages society – but particularly the upper class.

“The Tiger Flu also has roots in the Asian Avian Flu (H5N1) that began in Hong Kong in 2003 and arrived in Canada shortly afterwards,” says Lai. “The historical precedent for a selective virus, is, of course AIDS, which favoured a number of oppressed populations. But what if a disease came that afflicted the abusive and affluent instead?”

Rather than centering her novel on apocalyptic destruction and loss, as other speculative fiction authors might do, Lai purposefully chooses to focus on the potential for resilience, resistance, and the resurgence of life that inevitably emerge from oppression and strife: The community of Grist sisters utilises a range of ingenious biologically-based technologies to heal and enhance their bodies, Indigenous and other oppressed peoples form revolutionary coalitions, and a secret society of survivors hides in plain sight.

According to Lai, the long-awaited Tiger Flu is written in response to the works of feminist speculative fiction giants including Marge Piercy, Ursula K Le Guin, and Octavia Butler, and this lineage shows in the novel’s dizzying scope and depth of exploration into questions of politics, social organization, and human nature.

“[Speculative fiction] metaphorical possibility– that is the possibility to think through one’s stories and ways of being,” says Lai. “It offers us ways to imagine the worlds reconfigured with ourselves at the centre.”

In The Tiger Flu Lai inventively and provocatively centres the archetypes of the exile, the monster, and the dispossessed, fleshing out her characters with ferocity, genius, and vulnerability all at once – the character Kirilow is particularly spellbinding, capable of unyielding love and medical skill, as well as cruelty and foolishness. Driven to extreme heights of rage and grief by the atrocities committed against her Grist sisters by the ruling class of Saltwater City, Kirilow is forced to come to grips with her own hatred and the ways in which it prevents her from achieving her own healing.

The monstrous and exiled have always held a special interest for Lai. “I’m interested in writing from the point of view of the monster,” she says. “There are lots of precedents for this from Mary Shelley to Aimé Césaire to John Gardner. Of course, once you do this, the monster ceases being monstrous.”

Yet there is monstrosity, and violence, and bigotry in humans, and Lai’s commitment to hopefulness coexists with a frank examination of the more painful realities of sisterhood, community, and interdependence. In The Tiger Flu, some of the most painful wounds are dealt not only by the oppressor class, but by blood and chosen family.

One particularly notable example of this is tribe of Grist sisters, Lai’s rendering of a post-apocalyptic feminist community. Comprised of mutant clones who reproduce asexually, the Grists are depicted with unrelenting complexity rather than the utopian glow of other fictional all-female societies (the Amazons of Themyscira in Wonder Woman come to mind).

Historically persecuted and keenly aware of threats to their collective survival, the Grists impose a strict hierarchy upon their members and rely upon the bodily harvesting of “starfishes,” Grist sisters who can regrow their organs, in order to extend the lives of “doublers,” who possess the power of reproduction. It is the required sacrifice of Kirilow’s starfish lover, Peristrophe Halliana, that starts the chain of events that comprise Kirilow’s character arc in The Tiger Flu.

What follows is a dense, emotionally harrowing exploration of the infinite ways that women can both harm and heal each other. In The Tiger Flu, the sacrifice, harvest, and consumption of human beings – is dark mirror for all the myriad forms of exploitation that humans enact upon one another, including those we claim to love.

Lai does not shy away from the parallels between her novel and the context of queer people, diasporic people, and the politics in which she lives. “In a sense, the Grist sisters’ community is metaphorical for the community I inhabit. I already live there. I have no choice as to whether or not I want to live in it,” she says. “As a survivor of all the horrors that utopian thinking has dealt to Asians in particular, as hot proxy bodies for various ideological wars, I know better than to cling to too much purity. I’ve experienced first hand how no one can mess you up worse than your sisters in the struggle.”

The link between The Tiger Flu and real-life marginalized communities is a poignant one to make, particularly in the current political moment, when populism and identity politics are becoming ever more relevant to the struggles of everyday life.

Of Kirilow’s quest for vengeance against the “Salties” who have perpetrated genocidal violence against her people, Lai observes, “Here we have profoundly oppressed young person, using a politics of purity and expulsion– precisely the politics used against her people– in order to protect who and what she loves. Of course we have compassion for her. What she feels is absolutely understandable. And yet, she will become a murderer if she doesn’t grow.”

It is this sentiment that perhaps most succinctly captures the spirit of optimism that underlies The Tiger Flu, and Lai’s body of work in general: Against the backdrop of atrocity and despair, she illuminates the conditions which make human healing and growth not only possible, but necessary no matter the ultimate outcome.

This is what I find so captivating about The Tiger Flu. It refuses to give up on its characters and its world, even when they are perhaps beyond redemption. Lai offers us a gift, a chance to reclaim our faith in ourselves and each other, even as our utopian ideals crumble with the world around us.

Like its characters, The Tiger Flu isn’t perfect – like Salt Fish Girl before it, the book is deeply immersed in its own mythology, and the pacing moves from bracingly fast at the outset to lightning speed in the final act, which can result in some confusing moments. The plot twists come fast and furious, sometimes at the expense of allowing the reader time to sink into characters’ emotions and motivations. Yet the world and the story that Lai creates is so rich and so vivid that one cannot resist getting drawn in regardless.

The Tiger Flu isn’t just the story we want. It’s the kind of story that we need, that we deserve, that we have been waiting for in this time of utopian dreaming and dystopian reality. It’s a gift, and a reminder: We can be more than what we’ve been offered. We must choose more. We must choose each other, and life.

Vivek Shraya’s New Album “Part-Time Woman” Is a Binary-Breaking Love Letter

“I came to the conclusion that I don’t want to be a woman. I just want to be me. I want to be Sylvia Rivera.” Sylvia Rivera, trans feminine activist and icon, co-founder of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries

I wonder if it’s bad for the trans women’s movement to admit that I don’t always feel like a Full-Time Woman™. While I generally present exclusively in ways that conform to a stereotypical understanding of femininity – long hair, skirts and dresses, makeup, what in queer community is sometimes called “femme” and in trans community is sometimes called “fish” – the nuances of my gender identity, my internal sense of being, have always been more complicated than that.

And even as I write this, I can feel an old anxiety rising, the fear that I am betraying something or someone – my trans sisters? My self? – by expressing a personal truth that diverges from the simplified narrative that both politics and community so often demand.

So when I meet Vivek Shraya in my apartment on a rainy evening in Toronto to discuss her new album, Part-Time Woman, I am struck by how graciously she engages the charged subject matter of race, gender and representation. Shraya, a quadruple-threat trans girl art star who has garnered wide recognition in literature, film, photography, and music, is on her way to becoming a Canadian icon. Her work delicately troubles the boundaries of identity, eliding the usual political slogans to reveal rich shades of emotion.

“I really want trans girls to know that some of us don’t always have the right words or the powerful political declarations … in response to transphobia,” Shraya says with characteristic candor. “Some of us are struggling. Some of us are unsure. Some of us are slow to grow into who we are. I hope it brings comfort knowing that there are other people thinking about these things and singing about them too.”

Part-Time Woman is a deep and tender dive into that place of internal struggle and slow metamorphosis – giving lie to the misconception that pop music, Shraya’s chosen genre, is necessarily shallow or superficial. Shraya’s crooning vocals, set to the backdrop of original compositions performed by Toronto’s Queer Songbook Orchestra, ponder the meaning of “woman” and the experiences of those whose right to the word is contested terrain. In its six brief tracks, the album covers an impressive amount of thematic and musical ground; tracing an emotional arc from the balladic disappointment of “SWEETIE” and “I’M AFRAID OF MEN” which excavate the hypocrisy of the male gaze, through the contemplative longing of the titular number “PART-TIME WOMAN,” to the triumph of “BROWN GIRLS” and the final track “GIRL IT’S YOUR TIME” (a 1960s send-up which Shraya jokingly refers to as “the selfie of the album”).

Yet even triumph acquires new, complex dimensions in Part-Time Woman. Rather than attempting to replicate the anthemic, oversimplified (though admittedly delicious) feel of, say, Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way,” Shraya goes for something more textured, more grounded in the insecurities and resiliencies of day to day life that every girl – trans or cis, racialized or white – will recognize.

“For me, it was really important to end in a sort of celebratory way,” Shraya muses, “but the bridge [of “GIRL, IT’S YOUR TIME”] is like:

“GIRL, IT’S YOUR LIFE

BUT IT’S NOT YOUR WORLD

YOU’RE NOT ALWAYS SAFE

SO WHENEVER YOU’RE AFRAID

JUST KNOW YOU’RE ALWAYS MY GIRL

“So there’s this pain there too,” Shraya continues. “My reality as a trans girl isn’t this one, easy walk through life. It’s not always feeling desirable or feminine or safe or any of those things. And yet there is a celebratory tone in the album, because it moves from male gaze to self gaze and affirmation.”

Listening to Shraya muse on the way her life inflects her art, I think about my own mixed experience as someone whose life has arced through the identities of Chinese gay party boy to anarcho-punk non-binary femme to trans woman of colour writer. There are aspects of each part of that journey that I loved and mourned and missed. The increased confidence and sense of self that accompanied each shift has never negated the fear and loneliness and trauma. And yet I wouldn’t give up any parts of my past.

The juxtaposition of subtle joys and private grief is a theme that weaves throughout the album. Shraya’s strength is in her ability to take the listener with her to the edge of some very dark emotional places and then pull us back with a burst of unexpected insight.

Take, for example, the stark contrast of the final verse of “I’M AFRAID OF MEN,” in which she sings:

“ARE YOU HITTING ON ME?

ARE YOU HITTING ON ME?

OR ARE YOU GOING TO HIT ME?”

Followed by a beat of silence, and then the chorus

“IN MY HOUSE

IN MY HOUSE

DONT EVEN TURN THE LIGHTS ON

CAUSE I SHINE SO BRIGHT”

The song closes on a meandering brass solo that leaves the listener on the edge of their proverbial seat.

Shraya’s lyrics tease apart the ways in which trans girls’ emotional lives are drawings rendered in chiaroscuro, the play of light and shadow: The power and relief of discovering one’s identity in private intertwined with the pain of objectification and sexual violence.

This complex interplay is most evident in my favorite song in the album, the enigmatic “HARI NEF,” which is Shraya’s ode to the eponymous trans femme model and co-star of the hit sitcom Transparent. She sings:

“IS THE LEGACY OF BEING A GIRL

WANTING TO BE HEARD

TO BE HERSHE’S SO PRETTY BET HER LIFE IS PERFECT

SHE’S SO FUNNY BET HER LIFE IS FLAWLESSI WONDER IF SHE’S HAPPY BEING HER

OR IF LIKE ME SHE WANTS TO BE SOMEBODY ELSE”

There is something achingly resonant about this glimpse into the envy, longing, and empathy that exists between girls – something that takes on even more layers in the context of being trans and racialized. Trans girls of colour spend our whole lives either invisible or in the spotlight – it’s one or the other, never between. And so our womanhood either goes unrecognized or objectified, co-opted to satisfy someone else’s story about who we are.

In this polarized context, there is no room for ambiguity, for softness, for uncertainty or exploration. There is no room, in other words, to be human.

“I think that the way that people think about trans women is that [we] have to be totally confident or defiant all the time or that we all have similar politics and personalities,” Shraya confides. She goes on to describe the ways in which trans girls are sold a particular, restrictive mode of womanhood that is tied to normative ideals of beauty and race. “This [album] is a love letter to trans girls and a love letter to brown girls.”

This is a love that breaks through binaries and flowers in the margins. Lounging on a sofa with Shraya, talking and listening to the rain, I can feel tiny cracks opening in the walls of the labyrinth of labels, identities, and ideals in which we live.

Shraya, like all the best artists, is a storyteller whose vision both captures the world and in so doing, envisions a new one: A world in which you can still be anything. In which every person – man, woman, non-binary, all or no gender, or constantly changing – is exactly enough.

KOKUMO’s Galactic Bitch-Slap to the Literary Establishment

It’s almost midnight on a Saturday, and I am on suicide watch for two trans friends, two others are in crisis, I’m behind on paying my bills, and my caseload at my social work day job is on fire. Meanwhile, the establishment of the “LGBTQ movement” seems more interested in defending the rights of police to join Pride parades than it does actually helping trans people of colour and working-class queers survive. How wonderful to be living the queer writer-activist dream. As Chicago-based Black trans femme poet KOKUMO puts it in Reacquainted with Life: “are you invested in making the world a better place for all? / or just you and yours?”

In this moment of intense survival struggle in personal life — not to mention the current political climate of rising global right-wing fascism — it seems like there could be no better time to write about KOKUMO’s bombastic, fantastic Lambda Award-nominated Reacquainted with Life. Fresh from Brooklyn’s Topside Press, the debut poetry collection is an artistic coup that seizes the queer literary and political establishment by the shoulders and demands a reckoning. With her electric voice, searing gaze and unrelenting dedication to speaking truth, KOKUMO blasts through the bullshit rhetoric and tokenism that too-often engulf queer and trans communities in order to expose the raw struggle to survive at their heart. In the first line of the prologue, “GALACTIC BITCH-SLAP,” KOKUMO declares:

“1. Rape is theft.

2. Privilege is amoebic.[…]

13. Community is not currency.

14. Pain is not a rite of passage.”

The poetic intensity rises throughout the rest of the book. KOKUMO speaks both in generalities as well as directly to the complex dynamics of competition and intra-community violence that are an open secret among queer and trans people. This chord strikes particular resonance with me — as a social worker for trans youth, I’ve heard too many stories about community bullying, public shaming and social ostracization of the most marginalized: racialized folks, homeless folks, people living with mental illness. In my interview with her, KOKUMO says:

“Reacquainted with Life came to be after I had to leave the Trans Movement for my mental health. And it genuinely perplexed me how a movement said to have been my salvation could have been my doom. The tokenization. The femme competition/sabotage. The light-skinned supremacy. The respectability. The toxicity of having to constantly fight my oppressors and then the people I was dually being oppressed with […]

“This book came to be when I said I wouldn’t go quietly. I wouldn’t off myself so they wouldn’t have to deal with what they’d done. I was tokenized by my own ‘sisters’ and abused by men I called ‘brother.’ And again, I had to deduce that I wasn’t the only one. The thing they never tell you about ‘movements’ is that the engines run on the blood of the least ‘palatable’ […] Reacquainted With Life came to be when the movement told me I didn’t matter, but my soul said the fuck I don’t.”

Dispensing with poetic subtlety in favor of raw kinetic energy, KOKUMO nonetheless achieves enormous nuance of political and emotional expression. Where most writers might fear to tread, poems such as “Love Is Not the Revolution,” “Apology Panderin” and “White Feminist Barbie” speak without apology to the experiences of those who have survived not only queerphobia and transphobia but also the psychological and sexual violence of the queer movement itself.

Here is the truth that KOKUMO tells: Queers hurt queers. Ideology is not the same as love. Beneath the pretty words and shiny political analysis of the revolution lie harsh realities of transmisogyny, white and light-skinned supremacy, fatphobia and abuse. Movement leadership has done little to change the lives of the most marginalized. Consider “The Fame Monster (To the POC/LGBT Elite) (Part Une),” in which KOKUMO decries movement elites as “nothing more

than the ring leaders of a circus for abominations / with the nerve ta b choicey, / bout who get ta hop through the hoops.”

This poetry speaks to the gritty reality of life for queer and trans people who are fat, dark-skinned, crazy, poor – but it also affirms that life.

“This book was written expressly for fat femmes, for dark femmes,” KOKUMO says. “For fat dark femmes. For survivors. For perpetrators. For the survivors who have perpetrated. For the perpetrators who have survived. For the people who have the most plausible reason to abandon sanity but maintain a relationship with it because we have work to do. Bricks to lay. And bridges to burn.”

The book finds its climax in the titular poem, “Reacquainted with Life,” which is also the author’s favorite: “[This poem] is about returning from the abyss,” she says. “It’s about the world calling you trash, treating you as trash, but you still feeling a vigor and indignation […] Lazarus shit! I rose again. When I had what seemed to be more reasons to die than live. I still chose life. And no one or thing, will eva’ convince me to do anything otherwise.” This sentiment echoes strongly throughout the poem itself:

“wade through rocks

punch fist through earth

reach for the moon as if it were a life preserver”

Reacquainted with Life is powerful, necessary and not a moment too soon. It holds the map to a new way of thinking, of living, of being as queers. It asks us to sweep aside our shiny ideology and take a hard look at what we are doing to and with each other. It gives survivors of revolutionary movements — which, after all, tend to eat their children — the space they need to breathe.

And it is giving me the space I need to hold my own heart, on this night when everything seems to be on fire and in the morning, another trans youth might not be alive. In moments like this, the movement doesn’t save my life. Nor does community or the revolution. It’s poetry. Poetry, and the love it takes to speak the truth.

No World For Us: Broken Girls and Embodied Trauma in Porpentine’s “Psycho Nymph Exile”

Trans Girl knows a secret story — secret not only because she doesn’t tell it, but also because nobody wants to listen. It’s the story of what happens after she is driven out of a family that doesn’t want her, after she finds her way into “radical” communities that promise her safety, love and political empowerment. Those communities take her in, exploit her brilliance, assault her body, use her up, throw her away. She goes from magical symbol of the queer revolution to twice-outcast, doubly unloved. She becomes useless, becomes trash. Still, somehow, she survives.

In Psycho Nymph Exile, a speculative fiction multi-media storytelling experience that spans an online game, hypertext poetry, stickers (!) and a novella containing the central narrative, trans femme video game genius and self-described “America’s sweetheart” Porpentine Charity Heartscape takes the secret story and explodes it into a kaleidoscope of image, sound, heartrending prose, radioactive razor shards and toxic bodily fluids. The truth is all there, but shattered, rearranged for maximum sensory and emotional impact. Porpentine travels through a landscape of combat and broken flesh, unanchored in time or place, to map the effects of trauma on the bodies of the exiled.

“I’m interested in bodies that no longer have the thing that was supposed to be their primary reason for living,” Porpentine told Autostraddle. “A crystal, a womb, reflexes, membership in an institution. ‘Useless’ women. What they are left with is themselves. How frightening.”

Psycho Nymph Exile tells the love/trauma tale of Vellus Sadowary, a trans girl (Porpentine never uses the word “trans” to describe her narrator, and instead refers to her as a “hormone cyborg”) who lives in an all-female interdimensional reality where magical girls — think superheroes of the Sailor Moon variety — and giant living woman-shaped bioweapons roam the skies, locked in constant warfare. Vellus’s girlfriend and sole companion, Isidol, is an ex-magical girl whose crystal (the source of her magic) has been cut out of her body while she was asleep.

At the story’s beginning, Vellus is the pilot of one such “biomecha” weapon and a member of the prestigious Academy, a shadowy institution described only as “the most desirable place on earth, where we fly our giant war machines and hang out with friends with cool hair.” After a horrific accident (or perhaps sabotage) during which Vellus loses control of her biomecha during a mission, she is stripped of her position, viciously abused by her former comrades-in-arms and banished.

“Community [is] a golden sphere at the center of a deadly maze,” Porpentine says. And indeed, the parallels between Vellus’s experiences and to the collective gaslighting, abuse and ultimate rejection that so frequently happen to vulnerable people in tightly knit communities seems unmistakeable — especially paired with Porpentine’s critical essay “Hot Allostatic Load,” a more straightforward take on abuse, exile and trauma in queer communities. In Psycho Nymph Exile, she writes:

“It was the three months of solitary, or recommended rest, they called it, as she slowly figured out they didn’t want her to recount the incident as it had happened, but in a way that molded the incident into an unfortunate anomaly […] It was the disgust of the other academy members, the punitive sexual assault, and how so many of these things originated in people who had been ‘good’ to her before.”

Afterwards, impoverished and purposeless in a hostile world, Vellus is left to gather the fragmented pieces of her life. “When I was a kid, learning that people could be imprisoned for extended periods of time felt like the surest sign that this world is actually hell, and it felt insane that everyone else didn’t walk around filled with constant despair at the thought of it,” says Porpentine. In Vellus’s insane post-exile world, trauma is the only constant. Indeed, trauma suffuses every part of Pysycho Nymph Exile, from its motifs of monstrous body horror to its non-linear narrative structure to its hauntingly disaffected prose, which moves seemingly at random between first person narrative, third person narrative and textbook-style descriptions. For this is what trauma does: it breaks one’s sense of self and time, renders one’s perceptions of the body as hideous and harmful and cuts off all emotions save for terror and rage.

Porpentine goes a step even further, embodying trauma as a sort of character in the story as a biological disease winkingly named “DTSP” (Despair Syndrome with Temporal Purge), complete with a clinical symptomatology:

“Future death

Temporal displacement

Life-death

Psycho-irradiation

Pheromone poisoning […]

It is uncertain how people acquire DSTP. It seems entirely random. An innocent enough rape could be occurring when a beam of light falls from the sky and strikes a woman in the head, irradiating every cell of her body. Even women who have been utterly ostracized from society have developed this disease, in the absence of all contact.”

Every survivor of traumatic violence, trans or cis, will recognize themself in the description of DTSP, which Porpentine states that she chose to describe as a physical (rather than mental) illness simply “because people say it isn’t real. ”

In Psycho Nymph Exile, Porpentine builds a nightmare universe that is also oddly soothing in its willingness to take on unspeakable truths in the form of heightened, monstrous reality that, in the end, is not so much more monstrous than “true” reality at all. And, as with nightmares, the potential for allegory and allusion are endless: Porpentine’s giant biomechas driven by pilots who are only partially in control at best may be understood as references to dyshoria, while the endless war against an unknowable enemy whose face is identical to one’s own could be representative of the bottomless pit of ideological warfare in which the contemporary world is currently embroiled. Is the Academy queer community, or is it the school-to-prison pipeline, or is it the military industrial complex, or is it all three at the same time?

In some ways, it doesn’t really matter. Porpentine’s central thread tracks universal questions: Who are we, and what are we capable of, in exile? Without our defining relationships and the values that were supposed to give us a reason for living? What can we become? What are we worth, aside from what we can do or give to the community?

Psycho Nymph Exile is at its best when Porpentine is world-building with her signature aesthetic flair and attention to (horrific) details, or when fearlessly excavating sociopolitical dynamics where other writers might fear to tread. The online interactive pieces — “Probiotic River Therapy” in particular — are hauntingly beautiful, sensory evocations of trauma and dissociation.

However, the prose is sometimes surprisingly dense. A lot, perhaps too much, gets packed into the 188-page novella, and comprehension of the motifs require a bit too much “insider” knowledge of anime and cyberpunk tropes that might limit accessibility to readers with whom the story’s emotional arc might otherwise resonate. Additionally, the romantic relationship between Vellus and Isidol feels a bit underdeveloped; it’s hard to say what draws them to one another, aside from mutual brokenness (and in a narrative strewn with broken girls, one wants to know more).

But then, romance is secondary to the project of Psycho Nymph Exile: this is not, after all, anything close to a conventional narrative. It is a cartography of brokenness, an answer to the questions that no one wants to ask: What happens after exile? What happens to the girls who become trash?

Trans Girl knows a secret story: It is secret because no one wants it told. It is the story of how she survived, after all. And after she tells it, no one knows what she might become.

(Trans) Love and Other Scars: An Interview with Torrey Peters, Author of Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones

“Do not fall in love with people like me

we will take you to

museums and parks

and monuments

and kiss you in every beautiful

place so that you can

never go back to them

without tasting us

like blood in your mouth”

– Caitlyn Siehl, “Do Not Fall In Love With People Like Me”

Sometimes I miss the girl I used to be: That ferocious, electric, take-no-shit girl, the kleptomaniac poet survivor girl who was not afraid to punch someone in the face if she needed (or wanted) to. That girl was weirdly charismatic in her affected fearlessness and fast-talking eloquence, her militant activism for the cause of her own survival, her searing need to love and be loved.

She was volatile, vicious, full of self-loathing. She could have started a revolution. And sometimes I feel her writhing in me still, that girl I used to be.

Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones, the latest novella by Torrey Peters, makes that girl wake up and dance for grief and joy. Set in a dystopian future in which bioterrorism has rendered humanity incapable of organically producing sex hormones (think Mad Max, except with testosterone and estrogen instead of water), it is at heart a razor-edged, slyly funny love story of two literally and emotionally scarred women whose explosive relationship changes them — and their world — irrevocably.

The narrator and protagonist of Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones is an unnamed trans woman (“Patient Zero”) who longs for the ease and luxury of the upper-middle class life that she lived before her transition.Yet she is irresistibly drawn to antagonist/deuteragonist Lexi, a tempestuous, working-class, gun-obsessed trans girl whose simmering rage culminates in an act of devastating bioterrorism.

The gut-wrenching spiral of their relationship forms the emotional core of the book, and it burns in every scene that features them, as in the moment when Lexi infects the narrator with the carrier virus that ultimately brings about the paradigm in which everyone must fight to choose their gender:

“There’s a prick as the needle goes in, and when I pull my arm back, the point scrapes my skin. By the time I’m instinctively cradling my arm, blood is welling up. I’m in disbelief, looking at Lexi, trying to understand how somehow, it could have been a mistake.

“Now you’ll have a scar too,” says Lexi.”

Peters is a literary trailblazer on many fronts — her works of short and medium-length fiction defy classic genre categorization, throwing aside the conventions of mainstream literature to delve into the darker aspects of trans women’s psyches and relationships with signature gallows humor.(Her first novella, The Masker, is a devastating character study of a trans girl trying to find herself in forced-feminization fetish culture.) Peters, a graduate of the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop, also self-publishes as a politically conscious response to a literary world that “does not serve trans women.”

Torrey Peters

“The other benefit to self-publishing was that I can advertise that I give away digital copies for free,” says Peters. “No publisher would let me do that. I value readers more than profits, and given the chance, will always maximize my readership over my profits. The publishing industry as a whole is in trouble because they do the opposite.” Both Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones and The Masker are available on her website for pay-what-you-want or free.

“The entire project [of self-publishing] was about showing that there’s no barrier to access to emotionally move people,” she adds. “You don’t need a perfectly clean text, you don’t need an editor, you don’t need a press, all you really need is a will to write and an account with some self-publishing platform. The idea that you need a perfectly polished text to produce a work of art that people care about is a kind of gatekeeping. How many trans women have been denied on these kind of grounds? [Their] stories are important.”

It is precisely this commitment to the untold stories of trans women’s lives that allows Peters to create a narrative of emotional depth and accuracy that is rarely found in literary portrayals of trans women.In Lexi and the narrator of Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones, Peters paints portraits of two fully fleshed-out and flawed women in an affair that spans love, hatred, jealousy and regret — an impressive feat in a 70-odd page book.

The painful tension of the bond between Lexi and the narrator is pierces to the core of the struggle between internalized transmisogyny and trauma-bonded sisterhood that trans women share, as in this scene:

“I answered Lexi’s ad in the “t4t” section of Craigslist personals […] “Your girlfriend is really hot,” she said, and then paused and spun her beer coaster. “So, like, I don’t get why you’re here.” I didn’t know what to say. How do I tell a near-stranger that my girlfriend and I have only once had sex since I went on hormones? How that one time, with my cock hard and vulnerable, I looked down at her so gratefully […] just as she furrowed her brow and said disconsolately, “You smell different.” How just then, her face crumpled into tears? How I tried to get her to have sex anyway? How I wake every morning afterwards to her back, want to spoon her, but pull away from the chill of her grief, knowing that I beckoned it by my choice? […] Why did I want to meet Lexi? The answer is the things I can’t say.”

In this novella, Peters gives herself rein to go deeper into the intricacies of love between trans women — the chatspeak shorthand “t4t” and its implication of trans-for-trans love and sexuality is a recurring motif — than in any other work I’ve read.The gunpowder relationship between the vain, brand-obsessed narrator and the violently unstable Lexi resonates deeply with personal and political conflicts that most trans women must face in some way or another:

How do we choose to be trans in a world that hates us? Do we try and “pass” as best we can, strive to meet impossible beauty standards, align ourselves with cisgender people who offer us safety and comfort and simultaneously objectify us? Or do we try to carve out our own communities by tooth and nail, spit back in the face a world we’ll never really fit into anyway? Whom do we choose? Who will hurt us less? A cissexist society or each other?

In Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones, Peters captures this interpersonal and intrapsychic tension with heartbreaking precision: “A court of law, if a just one still exists or ever existed, might convict Lexi for her actions, but mine have been the thought-crimes: the cuts that no one could see or feel but Lexi. She had always known what I wouldn’t admit: I had been embarrassed of her […] I had been ashamed of the ways that I was like her, ashamed of the ways our transness made us sisters, if not lovers.”

Despite her enduring commitment to other trans women, Peters herself goes against the leftist-social-justice-warrior grain by resisting the idea of politically mandated community; instead, she articulates a concept of relationship based on “immunity,” or the freedom to choose.

“As a trans woman, I find the idea of immunity rather than community appealing,” Peters says. “What I just didn’t give a fuck? What if my baseline was ethical treatment of everyone, but what if beyond that, I get to choose my responsibilities and affinities for myself, rather than having them thrust upon me? […] I find crucial the distinction of choice over burden; the knowledge that I can safely fuck off to elsewhere if I so choose. I hang with trans women because I love them and understand them and want to care for them, not because I was somehow cosmically assigned to be responsible for them. I hope those women feel the same about me.”

The narrator of Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones puts it more caustically: “[Community was] a coven of trans women polyamorously fucking each other to biblical levels of drama over the soundtrack of Skyrim on PS3, all the while telling each other how shitty the world was away from each other, until they so confused micro-aggressions for deep violence that they walked around with knives in their boots and canisters of mace dangling from their purses.”

Girl, don’t I know it.

Love and the fear of loving other trans women are what transformed me, in the end. It allowed me to grow into someone softer and more open than the girl I used to be — and it has also destroyed me, tortured me, slain and buried me. Like many trans women, for a while I tried to forget who I was, tried to disappear as best I could. Infect Your Friends and Loved Onesis the kind that shakes and wakes that brave, mad, dangerous girl I used to be.

I’m glad. I have a feeling I’ll need her again, someday soon.

“Write what is missing in the world. Write the stories that could have saved you and weren’t there for you,” Peters says, in what sounds like both a prophecy and a pact. “I promise that you will have readers.”

When Death Makes You Kind: Beyond Survival In Gwen Benaway’s “Passage”

“A tough life needs a tough language – and that is what poetry is. That is what life offers – a language powerful enough to say how it is. It isn’t a hiding place. It is a finding place.” – Jeanette Winterson

Death is the specter that shadows all trans women, though it follows some more closely than others, and we may call it by different names. In her extraordinary book Passage, Indigenous trans woman poet Gwen Benaway takes both death and the reader by the hand to bring us on a journey through the Great Lakes of her ancestral home, trauma, trans femme desire, and above all, truth. With a gaze that is frankly astonishing in its clarity, Benaway holds up fragments of her life story, transforming autobiography into powerful testament to women who have been marked by violence, grief, and survival.

“now I try to breathe

your gelatinous body,

how your water held me

in soft suspension,

whenever I feel like

dying” – from “Lake Huron” in Passage

“Passage is a love letter to the lakes of my childhood,” says Benaway, who is of Métis and Anishnaabe descent, “If someone was to ask me where I come from, my clearest answer is those lakes. It’s where the Indigenous parts of my father’s family lived since the world began […] The Great Lakes is what brought my father’s family together and it holds our origin story. So in that sense, Passage is a reflection of ancestral waterways and our “beginnings” as a people.”

Yet the land also holds ghosts and grief for Benaway, as much as life and solace – a result of the violent atrocities of colonization and genocidal nation-building as well as the poet’s personal experiences. With understated grace, Benaway’s poetry travels through this haunted landscape, unearthing stories of loss that Eurocentric settler narratives of history have tried to forcibly forget:

“ancestral home, the Great Lakes

and the muskeg past them, boreal

veins where the dead camp,” she sings from the page in the poem “North Shore,” and later on in the piece,

“when I push past borders

hiding in a Northern truck stop

I find no road maps. just the memory of the dead

echoes of a people and a place

I only name in translation.”

As a settler of color who has lived in cities built on unceded, colonized First Nations territories for most of my life, my own relationship to the exploration of Indigeneity in Passage is clearly very different from the author’s. Yet the Indigenous roots of the book can not – must not – be ignored, for they are an essential facet of Benaway’s unrelenting pursuit of the truth in her poems, as are her experiences of gender and desire.

“So this funny thing has started happening,” Benaway says, “People have stopped introducing/referring to me by my Indigenous nations, Anishinaabe and Métis, and are just introducing me as “a Trans poet” […] Before transitioning, the focus was always on my “Indigenous” heritage. I think this reflects how white people value radicalized/marginalized people. We’re object lessons in tolerance and diversity for them.”

“so ask me again in your voice,

your eyes meeting mine, hands

seconds away from touching

what my life is about,

I’ll tell you I’m a priestess ,

summoning joy from a darkness

only I see.” – from “Kensington Series” in Passage

Marginality and the invisibilization of the body – the refusal of others to see Benaway for the Indigenous woman, survivor, person she is – is a central theme of Passage that weaves through many of its constituent poems. In spare, devastating language, Benaway confronts both her reality and of so many trans women and Indigenous women whose bodies have been seized, used, tossed aside – perhaps most climactically in the poem “Rescue,” which is a sustained, piercing cry of rage and mourning for the disappeared and the lost:

“I dream now

of retribution,

when the day

all the children

like me, the ones

with broken arms

and cut lips,

the starved

in basements

and shuffling

through hallways

like viruses

[…]

when I stop

waiting for the world

to find me and bring

my body home”

This poem is at once an testimony of the speaker’s survival and a confrontation of a society that allows – encourages – rape, abuse and oppression to happen. The implied question here is: Why didn’t you see me? Why didn’t you protect me? Why did you let this happen? Rather than answer this question directly, Benaway turns her gaze inward instead, demonstrating that she has already reclaimed her own personhood with the simple assertion and here / I am, not whole / but yes, still here / ready and willing / to be seen.”