Year of Our (Audre) Lorde: December’s Prologue

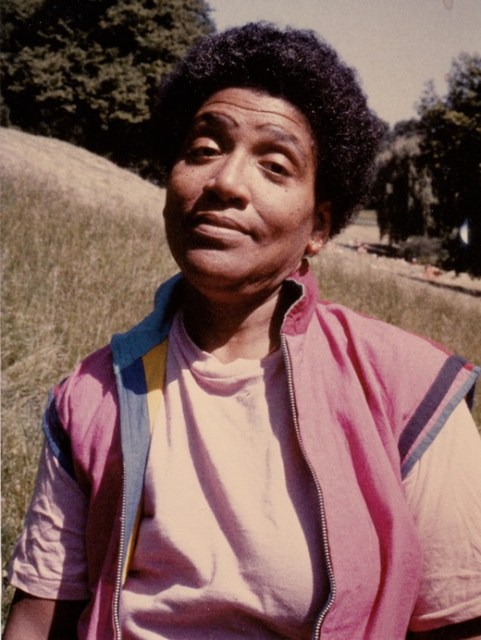

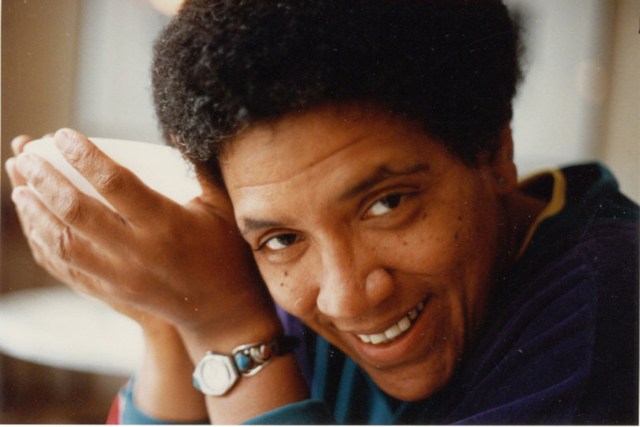

Feature photo of the author credit: Camilo Godoy

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde is a monthly analysis of works by queen mother Audre Lorde as they apply to our current political moment. In the spirit of relying on ancestral wisdom, centering QTPOC voices, wellness, and just generally leveling up, we believe that the Lorde has already gifted us with the tools we need for our survival.

I’d been hoping that by the time I reached the end of this experience I would have some sort of profound realization to share with you. There’s a comfort from epiphanies and tidy endings that I crave even though life keeps revealing the impossibility of that wish. Like so many other people I’ve been chirping about the end of 2020 as if the transition from one year to the next will magically suture the open wounds from this year. If anything, this year has made the unresolved issues from other difficult years resurface in spectacular fashion. There has been grief for the actual lives lost, but there has also been grief for the growing pains and the relational shifts occurring with loved ones, as I leave behind a self that was no longer serving me.

This year, one of the hardest of my entire life, was made so much brighter by reading and immersing myself in Audre Lorde, and by having this space to share with you all. As I’ve said before, reading Audre Lorde is a continuous reckoning that is always loving but not without its frictions. I’ve circled around the poem “Prologue” for months, unsure how I was meant to engage with it, but compelled by a larger force to not put it down. Even the beginning of the poem might give a clue as Lorde wrestles with her own tensions:

Haunted by poems beginning with I

seek out those whom I love who are deaf

to whatever does not destroy

or curse the old ways that did not serve us

while history falters and our poets are dying

choked into silence by icy distinction

their death rattles blind curses

and I hear even my own voice becoming

a pale strident whisper

Part of what Lorde is contending with is her work as a writer, the issues of voice and community that come up for each of us who have truths to share that, by nature, are inconvenient and uncomfortable. The pressures of those communities — chosen or otherwise — so often lead to the sort of icy silencing she mentions, because of how exhausting it is to keep holding tight to that truth.

One of the things I didn’t and couldn’t have expected was the blowback I would get for not traveling to be with my family of origin during this still ongoing pandemic — that a decision made out of deep love and concern for everyone’s health has been seen by some as selfish and self-serving. I’ve been called on repeatedly to defend myself and the choices I’ve made. It’s more painful than surprising, and while the hurt is still tender, this has also led to much deeper understandings of all the things we’re each carrying and how this pandemic has caused us all to grapple with the things we try to bury.

At night sleep locks me into an echoless coffin

sometimes at noon I dream

there is nothing to fear

now standing up in the light of my father sun

without shadow

I speak without concern for the accusations

that I am too much or too little woman

that I am too black or white

or too much myself

and through my lips come the voices

of the ghosts of our ancestors

living and moving among us

In writing this essay it’s occurred to me that maybe this particular poem was waiting for me to be ready for it. I had to get to the point of not merely analyzing Lorde’s words but attempting to live them. Looking over this year’s previous selections, there’s a recurring emphasis on resilience and on using your voice and your work in service of what you know to be right and just. This is part of Audre Lorde’s larger ethos, but it’s also what I most needed to receive.

The above lines resonate in an acute way — one of my greatest fears is that I’m “too much.” Insert whatever adjective you’d like and it would probably be something I worry about. Lorde’s focus on “too much or too little woman,” and “too black or white” get at the core of the matter. I think about all the ways that we’ve been taught these lessons of too much and not enough, and how we reinscribe the refrains on ourselves and on one another. And it was hard to fight the impulse that, in going against what others wanted me to do and who they wanted me to be for them, that I was wrong to make the choices I did. But as I sit with the pain of transitioning through the paradigm shifts of 2020, there is joy in knowing this pain feels better than the pain of the old world order.

Hear

the old ways are going away

and coming back pretending change

masked as denunciation and lament

masked as a choice

between eager mirrors that blur and distort

us in easy definitions

until our image

shatters along its fault

For me, “Prologue” maps out Lorde’s traumas and vulnerabilities, both in the moment of writing in the early 1970s and their roots in her early childhood experiences. Her crystalline ability to pierce through to the core of any issue shines through here, as she remains firm in the righteousness of her chosen path.

The pain Lorde feels is evident; but so, too, is the understanding that she’s a part of something bigger than the present moment. I always sense the spectre of death when I read the following lines, but I don’t find it morbid so much as communing with life’s many cycles and the import of our actions during our limited time in this realm.

Hear my heart’s voice as it darkens

pulling old rhythms out of the earth

that will receive this piece of me

and a piece of each one of you

when our part in history quickens again

and is over:

This is where I understood the futility of wanting a neat ending to this series.

There’s no way to wrap this up pretty nor orderly. Much like the many revelations and past traumas unearthed by these last 12 months, what I’m left with is mostly jagged edges and realizations that there’s so much more work to do, so much more to learn.

Somewhere in the landscape past noon

I shall leave a dark print

of the me that I am

and who I am not

etched in a shadow of angry and remembered loving

and their ghosts will move

whispering through them

with me none the wiser

for they will have buried me

either in shame

or in peace.

There’s much I will carry with me in the aftermath of this experience, and this lasting image of the dark print, “the me that I am and who I am not” is certainly one of them.

Lorde’s declaration here is one of her clearest reminders that what comes after us is not what others proclaim our works and our lives to be. Instead it’s our ability to live out our truths, to raise our voices in service of what needs to be said. Others can and will say what they want, but if we’re able to muster even part of Audre Lorde’s resolve, then we too will rest easy.

As we leave each other, I want to say that the opportunity for this column could not have come at a better time. When I began with a sort of simple desire to deepen my knowledge of one our queer ancestors, there was no way to know where this experiment would lead. More than anything, I’m grateful to those who read and engaged with Lorde’s words — and with me, as I’ve attempted to grapple with them this year. Thank you for journeying with me. I hope that this final column, this “prologue,” speaks to the new beginnings and also the continued lessons we may receive from Audre Lorde’s incomparable legacy.

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde: November’s Sister Love

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde is a monthly analysis of works by queen mother Audre Lorde as they apply to our current political moment. In the spirit of relying on ancestral wisdom, centering QTPOC voices, wellness, and just generally leveling up, we believe that the Lorde has already gifted us with the tools we need for our survival.

As much as I love reading Audre Lorde’s brilliance on its own, it’s an entirely different experience to read her in conversation with someone else. In some ways it helps to put Lorde in context as a more revealing look at who she’s dialoguing and thinking with, it gives an immediacy to her writing.

This month I’ve been reading her letters with Pat Parker in Sister Love: The Letters of Audre Lorde and Pat Parker 1974-1989. A birthday gift from my partner, I approached the letters as a welcome reprieve from the stress of the election and the renewed surges in Covid cases across the country. The letters between the two poets are funny, frank, and intimate above all else.

Their relationship is a testament to the enduring and life-affirming power of queer kinship. The correspondence spans 16 years, the ongoing resistance against Apartheid in South Africa, turbulent US politics at home and abroad, and the emergence of the AIDS crisis. The political and social climate they endured eerily aligns with the same genre of issues that have defined this year in particular, with the specific precarity of Black queer lives at the forefront.

This hilarious interlude from one of Pat Parker’s letters is one of my favorites, an explanation of sorts for her delay in responding to Lorde:

“Once upon a time there was this woman named Audre and she met this woman named Pat And she faithfully wrote her a letter. And for a long time she waited, but there was no answer. So Audre who knew that Pat lived in the land of the poet-killers assumed that her friend must be dead: for she knew that that was the only reason Pat hadn’t answered her letter. She knew that Pat wasn’t one of those ‘lazy n***.’ And one day out of the great smoggy blue a letter came and lo and behold it was from Pat and Audre rejoiced, for she knew that her friend wasn’t dead, but alas she had to admit and realized that her friend was indeed a ‘lazy n***.’ And the moral of this dyke tale, children, is that Pat Parker is alive and well but just a little more crazier.”

During the period of this collection of letters, both Lorde and Parker were diagnosed with breast cancer that went on to claim both of their lives — Pat Parker in 1989 and Audre Lorde in 1992. Yet even as they faced their own mortality, both encouraged the other and found moments of humor and triumph. In a 1986 letter, Lorde proudly informed Parker:

“Health wise I’m hanging in, gained 10 pounds which makes me feel really good (I was not born to be insubstantial and that’s how I was feeling last Feb when I saw you).”

Parker playfully responds, praising Lorde’s weight gain and saying she appeared “flat out skinny” and that Parker was ready to break out “chitterlings and hog maws” to help her regain weight. Yet the humor doesn’t mask Parker’s concerns and theories about her own diagnosis, as she speculates her anger, and primarily anger at their shared forms of oppression, led to her cancer:

“Why am I angry? Who am I angry at? And what can I do to change it? […] From the monumental thought of overthrowing the system and ridding my life of capitalism, racism, sexism, classism, to the smalles nuisance of getting Marty [Pat Parker’s partner] to put the toilet paper on the spool with the sheets unfolding outward, there is simply too much for me to handle. […] Sister love, sister love, sister love. We are not talking anything simple or easy here.”

Through it all, their enduring love attests to the power and beauty of Black queer sisterhood.

In particular, Lorde is attentive to her needs in a way that feels especially present as we move our actions back indoors, burrowing into colder weather and, arguably, an even more present sense of the increasing risk of Covid as cases rise to the worst numbers we’ve seen since the start of the pandemic. And while I’m leery of easy metaphors and making each moment a teachable one — I do think there’s a resonance between this season, this time we’re living in, and the attention that must be paid to what our inner selves for our collective survival.

Parker and Lorde’s relationship is like a mapping from inside out, directing us on how to build a life based on principles, writing the narratives you need to see out in the world and also radical love, vulnerability, and community as what makes it all possible. Sister Love is a window into a bygone era of coalitional politics that’s all too easy to romanticize in such a way that obscures the incredible amount of work it took to sustain their efforts. But it was without a doubt the best kind of work, with both Lorde and Parker mentioning organizations like Gente Latina de Ambiente and bygone lesbian/feminist publications such as Amazon Quarterly and off our backs. And while economic struggles were also discussed, it’s in the spirit of sharing resources. Lorde, as the older, more established poet, regularly tried to get Parker published in a journal or scheduled to perform at an event. She would also tuck bills into her letters for Parker. They both made sure to mention and promote the other and their work whenever possible, understanding that a spirit of competitiveness would never serve their shared cause of queer freedom and prosperity. Lorde laid it out explicitly:

“I have always loved you, Pat, and wanted for you those things you wanted deeply for yourself. Do not think me presumptuous—from the first time I met you in 1970 I knew that included your writing. I applaud your decision [to quit her job and write full-time]. I support you with my whole heart and extend myself to you in whatever way I can make this more possible for you. I hope you know by now that I call your name whenever I can and will continue to do so.”

Their sameness and shared sense of Black, lesbian identities reflected their most intimate selves, the fiery personalities and poetry both came to be known for. Their relationship teetered with multiple combustible elements, and what I love is seeing how they address whatever tensions arise head on, making it plain how much they loved and needed the other. One of Lorde’s letters speaks to this tension and this need with beautiful clarity:

“When I did not receive an answer to my letter last spring, I took a long and painful look at the 15 years we have known each other and decided that I had to accept the fact that we would never have the openness of friendship I always thought could be possible being the two strong Black women we are, with all our differences and sameness. Then your card came from Nairobi, and I thought once again maybe when I’m out there next spring Pat and I will sit down once and for all and look at why we were not more available to each other all these years.”

The balance Lorde strikes between love, candor, and vulnerability genuinely startles me; how much more “real” would our relationships be if we were able to state what we desire from the other in utter vulnerability?

It has felt hard to state how much I’ve been missing my family lately — both originary and chosen. For weeks now I’ve semiconsciously opted to power through, convincing myself that the experience of the sudden lockdown this spring had prepared me for the sharp wave of loneliness that’s appeared. But in reading Sister Love I came across a necessary reminder that it’s in articulating what we’re feeling that we’re able to name our pain and reclaim ourselves from it. Parker’s words perfectly capture this realization:

“Started seeing a therapist with Marty and individually and it’s proved to be quite helpful despite my resistance. It’s hard for us strong Black women types to admit we’re fucking falling apart at the seams as you must well know.”

Ultimately, what I appreciate more than anything is how Lorde and Parker illustrate the importance of never losing sight of our work as artists and creators, what we put into the world, nor losing sight of each other. At each turn, they encouraged each other to speak her truth and the importance that each woman’s work carried.

In a particularly loving exchange where Lorde affirms Parker’s recent decision to quit her job and write full time, Audre Lorde gifts her with a timely message that speaks to the need to hold steady — and guard fiercely — the shared space inside ourselves as the place where we can live and flourish:

“Things you must beware of right now–

A year seems like a lot of time now at this end—it isn’t.

It took me three years to reclaim my full flow. Don’t lose your sense of urgency on the one hand, on the other, don’t be too hard on yourself—or expect too much.

Beware the terror of not producing.

Beware the urge to justify your decision.

Watch out for the kitchen sink and the plumbing and that painting that always needed being done. But remember the body needs to create too.

Beware feeling you’re not good enough to deserve it

Beware feeling you’re too good to need it

Beware all the hatred you’ve stored up inside you, and the locks on your tender places.”

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde: October’s Dead Is Behind Us

Photograph of author by Camilo Godoy

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde is a monthly analysis of works by queen mother Audre Lorde as they apply to our current political moment. In the spirit of relying on ancestral wisdom, centering QTPOC voices, wellness, and just generally leveling up, we believe that the Lorde has already gifted us with the tools we need for our survival.

A friend once told me that the time around Halloween is when the veil between this world and the next slips away, and our connection to the spirit world is at its highest. (This was before either of us had seen Coco.) It’s a reminder I carry with me, a wisdom I call upon that speaks to the multiple worlds we all inhabit, and the connections that defy common conceptions of time and space.

In her poetry collection Our Dead Behind Us, Audre Lorde contradicts the very claim of her title by revealing all the ways we carry our dead alongside us, within us, into our everyday and into the future. It’s a necessary re-framing of grief and time; and, true to form, Lorde is always in time. This collection feels sankofic; a look backwards, an engagement with history while the feet are pointed forward, headed into the future.

As the end of the longest year in history inches closer, I’ve been challenging myself to sit with the many losses that have characterized 2020, to reframe them as not a lack or a “negation of” — but as a series of ongoing paradigm shifts. Death takes on many forms; it’s not only the transition from this plane to another, but encompasses these shifts — within relationships, understandings of ourselves and others, and ways of being in the world. The poem “Mawu” speaks perfectly to this sense of reckoning and acceptance:

“Released / from the prism of dreaming / we make peace with the women / we shall never become / I measure your betrayals / in a hundred different faces / to claim you as my own / grown cool and delicate and grave / beyond revision / So long as your death is a leaving / it will never be my last.”

I’ve been thinking a lot about an experience I had last year. During a sacred ritual with

some ordained elders, one Baba came up to me and said, “You have a grandmother who walks with you. She’s here with you now. And every day.”

I hadn’t shared anything about my grandmother throughout the ritual, hadn’t even said Nana’s name aloud in the days before. But then he told me she was with me, always, and it was as if I fell into an alignment, like he offered a shape to her in the present moment. I hadn’t even read the poem “Call” by then, and yet I was embodying it:

“I am a Black woman stripped down / and praying / my whole life has been an alter / worth its ending / and I say Aido Hwedo is coming.”

(Aido Hwedo: The Rainbow Serpent; also a representation of all ancient divinities who must be worshipped but whose names and faces have been lost in time.”)

To be Black in this world is to be intimate with a kind of living death. It’s an intimacy no one craves, and yet Black people know better than most that Lorde speaks truth to power in saying “we were never meant to survive.” Whether we lose a grandmother or an aunt, or whether it’s Breonna Taylor, who we only come to recognize in the aftermath of her death, each loss feels personal and tethered to the next. And while we need to attend to the ways in which we #SayHerName, I think it’s important to evoke all those who are gone, especially those who die unnatural deaths borne from racism, queer and transphobia, unequal access to healthcare, and the numerous other ways this world actively tries to kill us.

Lorde, as prescient as ever, offers writing as an act of remembrance, of both engaging with the dead and affirming the truth of our living in “Learning to Write”:

“I am a bleak heroism of words / that refuse / to be buried alive / with the liars.”

I think this sentiment is one she also reaffirms beautifully in “Burning the Water Hyacinth:”

“Plucking desire / from my palms / like the firehairs of a cactus / I know this appetite / the greed of a poet / or an empty woman / trying to touch / what matters.”

Like so many people, for me part of grappling with the torrent-of-everything that is 2020 is acknowledging that this year is an accumulation of misdeeds, misrecognitions, and unaddressed issues all surfacing at once. Under each of the issues we’re contending with is the question of how we got here, and what do we do now that we are still here, certainly for the foreseeable future. The above lines from “Burning the Water Hyacinth,” about attempting to “touch what matters,” could be a banner proclamation for so many of us. Touch (or the lack thereof) has forcibly organized how we engage with one another, show love and affection, and attempt to bridge the distances furthered by the many multiple pandemics of 2020.

What Audre Lorde has demonstrated time and again is that touching what matters is the kind of touch that doesn’t reach wide but rather burrows deep, fingers submersed in the earth in order to get at the root of it all. This extended period of time we’ve currently spent with ourselves has propelled some of the deepest self-reflection we’ve allowed ourselves in years. Like how it took me getting into my thirties and the force of global pandemics to really write about the relationship that shaped most of my twenties. As hard as it is to admit, the death of that relationship was so acute, it took nearly seven years of reflection — rehashing the worst moments, doubting myself, hearing her voice each time I failed or misstepped, and discovering and rediscovering that familiarity — before I finally was able to put the worst of it to rest.

I’m no longer who I was before that relationship. And the process of confronting the myriad implications of that experience is ongoing. As Lorde states in the poem “Outlines”:

“When women make love / beyond the first exploration / we meet each other knowing / in a landscape / the rest of our lives / attempts to understand.”

After my first true heartbreak, it took several years post-mortem to realize I’d been living in response to that experience. My relationship with her was the most toxic I’d ever experienced and yet its ending felt like a death to me, one that foreclosed a future I saw for myself, for us. The self I inhabited was one formed against the sharpness of that loss, one I projected to convince myself — but really to convince her — that I was the antithesis of who she thought I was. From “Stations”:

“Some women wait for themselves / around the next corner / and call the empty spot peace /but the opposite of living / is only not living / and the stars do not care.”

There’s no easy resolution here.

It would be an empty filler to simply gesture at 2021 as a healing balm for all the dying and living we’re experiencing right now. Most years, Halloween season is a deeply welcomed comfort — an annual communion across the veil that fortifies me. I can’t say I feel that same fortifying power this year, certainly not in any way that offers a sense of assurance.

But what I’m realizing is that the ritual I’ve developed in this column, communing with Audre Lorde for these last ten months, has at least instilled a belief in me that our archival, ancestral engagement is part of our lineage of survival. She details this lineage pristinely in “On My Way Out I Passed Over You and the Verazzano Bridge:”

“I am writing these words as a route map / an artifact for survival / a chronicle of buried treasure / a mourning / for this place we are about to be leaving / a rudder for my children your children / our lovers our hopes braided / from the dull wharves of Tompkinsville / to Zimbabwe Chad Azania / […]History is not kind to us / we restitch it with living / past memory forward / into desire / into the panic articulation / of want without having / or even the promise of getting. / And I dream of our coming together / encircled driven / not only by love / but by lust for a working tomorrow / the flights of this journey / maples uncertain / and necessary as water.”

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde: September’s Afterimages

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde is a monthly analysis of works by queen mother Audre Lorde as they apply to our current political moment. In the spirit of relying on ancestral wisdom, centering QTPOC voices, wellness, and just generally leveling up, we believe that the Lorde has already gifted us with the tools we need for our survival.

There’s so much that can be said, that seeks articulation in the wake of the Breonna Taylor verdict. After the ravages of this year, the anger and fear that comes along with the decision to value property over a Black woman’s life feels to me like an unbearable weight. The pain is raw and too tender to try and explicate now; the fear that I am safe nowhere, the Black women in my family of origin and family of choice are safe nowhere. It’s a fact we’ve known but one that feels all the more threatening in the wake of continuing injustice for Black women.

At the same time, we’re faced with the utter devastation that has ravaged the West Coast. As I write this, I’m curled under a sweater and blanket in an unseasonably cold apartment whose heat hasn’t been turned on yet. The cold is a result of the hazy gray saturating the sky in upstate New York and so much of the country as the smoke from the fires moves farther and farther east. Whether for the best or the worst of reasons, we are all connected to each other. The pain of others, of our Earth is viscerally real.

There’s an immediacy to the recent razing of the West Coast that demands our attention. As it should. Especially knowing that the devastation, we’ve learned, was not only preventable but premeditated. Like so much of the pain and loss of 2020, it simply did not have to be this way.

I wrestled more with this month’s choice of focus than I have any other. I was captivated by Audre Lorde’s startling use of imagery as much as I was disturbed by the pain and discomfort she stirred up. The poem “Afterimages” is Lorde’s juxtaposition of nature, violence, and loss.

In one vignette there is a white woman standing near the Pearl River in Mississippi after a hurricane, stilled by shock at all she’s lost to the storm. In the over vignette we are still in Mississippi, but decades earlier when the body of young Emmett Till is found.

however the image enters

its force remains

I can’t even begin to explain how tired I am of being made to bear witness to Black death and to the destruction of Black life. But I think what’s different here, what Lorde witnessed with the highly publicized account of Till’s murder was the power of the image. I suspect that for most of us Emmett Till is perhaps the first image of Black death and murder we encounter, at least on a nationwide scale. His mother crying over his distorted face in that open casket is one I will never forget. But what’s happened in our complete saturation cycle of images and videos of Black death is a numbness, or at least an uneasy sense that this is commonplace. I’ve seen on Twitter and elsewhere multiple comments on the use of Breonna Taylor’s name and image to promote everything from sporting events to social media influencers, yet she was denied her life and — in the aftermath — any sense of justice. The fires ravaging the Western U.S. are growing to be expected each year. Our climate crisis grows more and more perilous and again we are uneasy in how commonplace it is.

In each of these instances, it’s not that these atrocities happen — it’s the scale that is newsworthy. What’s just as important here is that Lorde’s calling into question so many crises that have been “naturalized” in one sense or another. The destruction of nature itself is utterly violent and completely unnatural. The disregard for Black life, the casual and frequent murders of Black people are utterly violent and completely unnatural.

A white woman stands bereft and empty

a black boy hacked into a murderous lesson

recalled in me forever

like a lurch of earth on the edge of sleep

etched into my visions

food for dragonfish that learn

to live upon whatever they must eat

fused images beneath my pain.

It’s not nearly as simple as the water which characterizes both of these figures. What Lorde does here is draw our attention to how we become inured to these violences, these assaults on nature — both the environment(s) we inhabit and our human nature, our shared humanity.

The Pearl River floods through the streets of Jackson

A Mississippi summer televised.

Trapped houses kneel like sinners in the rain

a white woman climbs from her roof to a passing boat

her fingers tarry for a moment on the chimney

now awash

tearless and no longer young, she holds

a tattered baby’s blanket in her arms.

In a flickering afterimage of the nightmare rain

a microphone

thrust up against her flat bewildered words

“we jest come from the bank yestiddy

borrowing money to pay the income tax

now everything’s gone. I never knew

it could be so hard.”

[…]I inherited Jackson, Mississippi.

For my majority it gave me Emmett Till

his 15 years puffed out like bruises

on plump boy-cheeks

his only Mississippi summer

whistling a 21 gun salute to Dixie

as a white girl passed him in the street

and he was baptized my son forever

in the midnight waters of the Pearl.

What strikes me most about these lines from the poem, and its title, is that Lorde is once again demanding that we don’t look away. We are bombarded with so many of these images now and so many of these videos, data visualizations, and more of these devastations. But what Lorde is articulating is that we must register them as the individual losses they are.

Each incident haunts her as each of the incidents this year haunts me and I’m sure haunts most of us. But after this news cycle, after the fires die down, we cannot seek to erase the after images. We have to do all we can to ensure that these atrocities do not continue.

His broken body is the afterimage of my 21st year

when I walked through a northern summer

my eyes averted

from each corner’s photographies

newspapers protest posters magazines

Police Story, Confidential, True

the avid insistence of detail

pretending insight or information

the length of gash across the dead boy’s loins

his grieving mother’s lamentation

the severed lips, how many burns

his gouged out eyes

sewed shut upon the screaming covers

louder than life

all over

the veiled warning, the secret relish

of a black child’s mutilated body

fingered by street-corner eyes

bruise upon livid bruise[…]

and wherever I looked that summer

I learned to be at home with children’s blood

with savored violence

with pictures of black broken flesh

used, crumpled, and discarded

lying amid the sidewalk refuse

like a raped woman’s face.

When she says she learned to “be at home with children’s blood,” I think Lorde is giving us a warning. We cannot naturalize this. The unnatural nature of the hurricanes she writes about, the fires we know continue on today, and the open killing of Black people all over this country are anything but natural disasters. We need to stay attuned, not only to the fact that these things keep happening, but to the ways in which we’re conditioned to passively consume Black death and the ravaging of our planet.

Within my eyes

the flickering afterimages of a nightmare rain

a woman wrings her hands

beneath the weight of agonies remembered

I wade through summer ghosts

betrayed by vision

hers and my own

becoming dragonfish to survive

the horrors we are living

with tortured lungs

adapting to breathe blood.

I think about the relationship between blackness and land a lot. As the descendant of enslaved people, that relationship used to be so fraught, more of a weariness of strange fruit than anything else. But in pushing beyond my initial discomfort, I came to realize that the problem isn’t the land but what humans do to it. There is a disposability, a capitalist consumption of land and labor and Black people and Indigenous folx, for anything and anyone that supplants the unquenchable hunger for our lives.

Audre Lorde implores us to bask in the difference, yet in “Afterimages” she articulates her own struggles with the task that she herself requires. It is anything but easy to witness so much of your own people’s destruction, wear your voice thin by decrying the injustices, and then watch that destruction ripple into others. While the differences are there, what Lorde so beautifully and achingly makes clear is that one person’s ruin will soon lead to another’s.

We can no longer adapt to breathing blood.

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde: August’s New Spelling of My Name

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde is a monthly analysis of works by queen mother Audre Lorde as they apply to our current political moment. In the spirit of relying on ancestral wisdom, centering QTPOC voices, wellness, and just generally leveling up, we believe that the Lorde has already gifted us with the tools we need for our survival.

As a writer who recently moved out of New York, the temptation is great to contribute to the genre of “Leaving New York” essays. So great, in fact, that I can’t pass up the opportunity entirely.

After seven years and nearly as many apartments, I left New York. I left because I’m beginning a Ph.D. program upstate. And while deciding to return to graduate school after a 5-year hiatus certainly comes with its own challenges, it was the challenge of New York I’ve found myself clinging to. While the New York I inhabited and the one of Audre Lorde’s life looked radically different in most respects, in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, Lorde nonetheless captures so much of the city’s gritty vibrancy and its unrelenting pace, whether good or insufferable.

For me, New York was the city that tested my willingness to contend with myself, with others, and with elements you cannot begin to foresee until you find yourself on a subway platform with a baby squirrel-sized rat running an inch in front of your feet and a man older than your father offering you *all* his food stamps in exchange for your phone number (these were, thankfully, two separate incidents). Along with the hilarious and “only in New York” stories came the moments where the city stripped me of so many comforts, left me broke and broken more than I’d ever been before. But it has also left me stronger, more daring, and the fullest version of myself, a self I’d been too scared to think possible in any other place I’d lived.

For Lorde, New York was both question and answer, the reason to escape and the queer refuge after fleeing her parents’ house as a teenager. Although born and raised in Harlem, she leaves and returns, leaves and returns New York throughout the events charted in the book. Early on, she notes that as the child of immigrants, she always conceived of home as a distant somewhere that bore the promise of belonging not afforded her strict, deeply religious family in Depression-era Harlem.

“Once home was a far way off a place I had never been to but knew well out of my mother’s mouth. She breathed exuded hummed the fruit smell of Noel’s Hill morning fresh and noon hot, and I spun visions of sapadilla and mango as a net over my Harlem tenement cot in the snoring darkness rank with nightmare sweat. Made bearable because it was not all. This now, here, was a space, some temporary abode, never to be considered forever nor totally binding nor defining, no matter how much it commanded in energy and attention. For if we lived correctly and with frugality, looked both ways before crossing the street, then someday we would arrive back in the sweet place, back home.”

It becomes clear that the home Lorde is searching for is one not to be found with her family of origin, but a sense of belonging and rest that only she is able to make real.

But I’d be lying if I said Zami was initially an easy read. I didn’t so much as pick the book as I did wrestle through the beginning chapters for most of February before tucking it away until July. By FebruaryI knew I’d be moving, but had no idea that the world as I knew it and moved around in it would implode so quickly. That it would shrink itself to an apartment and carefully plotted grocery store and pharmacy runs. I’d been told for years I needed to read Zami, especially because of how Audre Lorde captures a lesbian scene no longer in existence in New York. But I kept getting lost in the deep dives into her childhood, too uncomfortable with the highly restricted Harlem of her early years and the many physical, cultural, and psychic limitations she endured. What I couldn’t see then was how Lorde was intentionally teasing out how we are shaped and how we create ourselves out of those experiences.

It was this quote that made Lorde’s self-mythology become evident to me:

“But it was so typical of my mother when I was young that if she couldn’t stop white people from spitting on her children because they were Black, she would insist it was something else. It was so often her approach to the world; to change reality. If you can’t change reality, change your perception of it.”

My initial discomfort with Zami stemmed from a misunderstanding of Lorde’s aim. I hadn’t yet realized that Audre Lorde was queering the genre of memoir/autobiography, hyperbolically employing the structure of the hero’s journey, folklore, and mythology in order to carve a space for herself and others like her.

Lorde fashioned Zami as a biomythography. While the term has been interpreted and re-interpreted many times over the years, I think Lorde is examining the stories and experiences we collect, that we tell ourselves time and again. In doing so, we are inscribing them as our self-mythologies. From the personal to the national, Lorde examines the power of myth as she employs it to write and rewrite her own journey into that same tradition.

“I remember how being young and Black and gay and lonely felt. A lot of it was fine, feeling I had the truth and the light and the key, but a lot of it was purely hell. There were no mothers, no sisters, no heroes. We had to do it alone, like our sister Amazons, the riders on the loneliest outposts of the kingdom of Dahomey. We, young and Black and fine and gay, sweated out our first heartbreaks with no school nor office chums to share that confidence over lunch hour. Just as there were no rings to make tangible the reason for our happy secret smiles, there were no names nor reason given or shared for the tears that messed up the lab reports or the library bills. […] We did it cold turkey, and although it resulted in some pretty imaginative tough women when we survived, too many of us did not survive at all.”

That so much of Zami takes place in and around New York really speaks to me, especially now that I’m no longer there. As one of those rare sites that actually lives up to its myths, New York has been a known harbor for those of us at the margins for decades. This was certainly true in Lorde’s lifetime. I don’t fancy myself nearly as strong or resolute as Lorde; I don’t know that I would have emerged as intact as she did on the other side of so many hardships. But where our experiences overlap is in the power of the city to make you known to yourself, to articulate a desire and to have that desire, that longing reflected back to you. Lorde came into her queerness in New York. So did I.

Rather than obscure the wounds, the losses of the many people and places who were sure to let her know she would not find home within them, Lorde makes a home out of herself. She finds shelter with the many women she loves and within New York, but home is within her, within Zami as a reparative work and an act of world-building. Zami opens up a place she can inhabit.

“In a paradoxical sense, once I accepted my position as different from the larger society as well as from any single sub-society—Black or gay—I felt I didn’t have to try so hard. To be accepted. To look femme. To be straight. To look straight. To be proper. To look ‘nice.’ To be liked. To be loved. To be approved. What I didn’t realize was how much harder I had to try merely to stay alive, or rather, to stay human. How much stronger a person I became in that trying.”

New York is so often the site of contemporary myths because it is one of those rare places that is a verb, an act of regularly reckoning with yourself. So, too, is Zami. Both the city and the book share a slightly elusive, ephemeral quality. But in quintessential Lorde fashion, and thus quintessential New York fashion, the undercurrent of her writing suggests a single lifted eyebrow, slyly asking “are you ready for me?” Both are always ready to offer an embrace and a challenge. It probably won’t come as a surprise that Zami has become my favorite Audre Lorde read thus far.

Audre Lorde’s relationships and the women she loves and lusts for each leave her fuller than before. And while Lorde eventually does leave New York for good, she continues to cycle through the city for the rest of her life. My guess is that beyond family ties, Lorde needed to feel and draw from the city’s power every now and again.

In my own myth, New York has certainly been the cornerstone of so much of what has shaped me, particularly in knowing myself and finally allowing myself to be in my queerness. It’s where most of my community is, those women I love who continue to help me along my own journey.

The reckoning continues. And I find joy in knowing New York and I — Lorde and I — aren’t nearly done with each other.

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde: July Is a Black Unicorn

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde is a monthly analysis of works by queen mother Audre Lorde as they apply to our current political moment. In the spirit of relying on ancestral wisdom, centering QTPOC voices, wellness, and just generally leveling up, we believe that the Lorde has already gifted us with the tools we need for our survival.

The language of our time traffics in a lot of terminology that’s so commonplace, the words can lose their potency. I think a lot about the term intersectionality in particular, a brilliant distillation by Kimberlé Crenshaw of the multiple positionalities of marginalized folks. What sometimes gets lost in the use of this term is how absolutely exhausting it is to straddle multiple places and boundaries. Intersectionality is active, requiring a constant calibration between the various identity places you hold, choosing which parts of yourself to emphasize or not. An intersection is a geography — but it is also a place of in-betweens.

For me right now, that in-between is the pandemic within the pandemic, the ongoing issues facing Black people, especially Black queer and trans folks. Dwindling news coverage means dwindling urgency and hope for the reckoning we know we need, but fear will continuously be signaled at and never fully delivered.

What I love most about Audre Lorde’s The Black Unicorn is how she’s able to crystallize the experience of intersectionality — the feelings of exhaustion, fury, disgust, and hope.

In the title poem, she writes:

The black unicorn is greedy.

The black unicorn is impatient.

The black unicorn is mistaken

for a shadow

or symbol

and taken

through a cold country

where mist painted mockeries

of my fury.

It is not on her lap where the horn rests

but deep in her moonpit

growing.

The black unicorn is restless

the black unicorn is unrelenting

the black unicorn is not

free.

I’m still angry. I’m still exhausted. The ways in which the outrageousness of this moment have begun to take on a sense of normalcy are both necessary and frightening. Breonna Taylor’s murderers still walk free. And let’s be real, they’re probably running around without masks. Lorde’s own sense of depletion, of restlessness and barely concealed fury are evident in this poem. But so, too, is her unwavering belief in our magic. I keep re-reading this poem trying to conceive of what she means by the Black unicorn.

I want to know how were these terms used then, in 1978 when The Black Unicorn was first published. Was Audre Lorde referring to herself as a unicorn? To all Black people? A defining characteristic of the unicorn is its solitary nature. While Lorde’s unicorn is an obvious reference to race, blackness is also a subversion here, because blackness itself is inherently a tether. It’s a tether to the histories of time and space and race that have come to define our journeys on this plane.

The themes of solitude and of a belonging so enmeshed with violence and grief resonate throughout the collection. In the poem “Outside,” Audre Lorde lays bare this tension in beautifully tender verse. She writes:

In the center of a harsh and spectrumed city

all things natural are strange.

I grew up in a genuine confusion

between grass and weeds and flowers

and what colored meant

except for clothes you couldn’t bleach

and nobody called me nigger

until I was thirteen.

Nobody lynched my mama

but what she’d never been

had bleached her face of everything

but very private furies

and made the other children

call me yellow snot at school.

And how many times have I called myself back

through my bones confusion

black

like marrow meaning meat

and how many times have you cut me

and run in the streets

my own blood

who do you think me to be

that you are terrified of becoming

or what do you see in my face

you have not already discarded

in your own mirror

what face do you see in my eyes

that you will someday

come to

acknowledge your own?

Who shall I curse that I grew up

believing in my mother’s face

or that I lived in fear of potent darkness

wearing my father’s shape

they have both marked me

with their blind and terrible love

and I am lustful for my own name.

Between the canyons of their mighty silences

mother bright and father brown

I seek my own shapes now

for they never spoke of me

except as theirs

I read this collection backward and forward, trying to figure out what compelled me to choose it for this month’s focus. Arguably the biggest difficulty of a series like this is determining which piece(s) speak to the present moment we’re in. What I love about The Black Unicorn is Audre Lorde’s continued insistence that our plight as Black people, as queer people, as women is forever a timely issue.

We are more than talking points, more than a trending Twitter topic. The issues we bring to light are at the center of our lives and our attempts to survive our inheritances. I found myself both nodding and wincing at the vulnerability and longing throughout Lorde’s writing. So often as queer Black women we’re required to perform our pain so our humanity can be rendered as real. And while it’s important to remember Audre Lorde is a product of a time that demanded such performances, she nonetheless refused to make herself palatable. Lorde’s message is a challenge for white people to be better and to do better by those whom they oppress.

In “Power,” Audre Lorde continues enacting the need for poetry with this reminder: “The difference between poetry and rhetoric / is being / ready to kill / yourself / instead of your children.” She goes on to write:

The policeman who shot down a 10-year-old in Queens

stood over the boy with his cop shoes in childish blood

and a voice said “Die you little motherfucker” and

there are tapes to prove that. At his trial

this policeman said in his own defense

“I didn’t notice the size or nothing else

only the color.” and

there are tapes to prove that, too.

Today that 37-year-old white man with 13 years of police forcing

has been set free

by 11 white men who said they were satisfied

justice had been done

and one black woman who said

“They convinced me” meaning

they had dragged her 4’10″ black woman’s frame

over the hot coals of four centuries of white male approval

until she let go the first real power she ever had

and lined her own womb with cement

to make a graveyard for our children.

I have not been able to touch the destruction within me.

But unless I learn to use

the difference between poetry and rhetoric

my power too will run corrupt as poisonous mold

or lie limp and useless as an unconnected wire

and one day I will take my teenaged plug

and connect it to the nearest socket

raping an 85-year-old white woman

who is somebody’s mother

and as I beat her senseless and set a torch to her bed

a greek chorus will be singing in ¾ time

“Poor thing. She never hurt a soul. What beasts they are.”

Lorde lives in the in-betweens: between power and disempowerment, fury and sorrow, hope and longing, life and death. The activeness and the labor of her intersectional living take their toll; it requires an intimacy with the precariousness of a life in the between. In “A Song for Many Movements,” Lorde writes:

Nobody wants to die on the way

caught between ghosts of whiteness

and the real water

none of us wanted to leave

our bones

on the way to salvation […] Broken down gods survive

in the crevasses and mudpots

of every beleaguered city

where it is obvious

there are too many bodies

to cart to the ovens

or gallows

and our uses have become

more important than our silence

after the fall

too many empty cases

of blood to bury or burn

there will be no body left

to listen

and our labor

has become more important

than our silence.

Our labor has become

more important

than our silence.

In the same year that this volume was published, Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer for the first time and underwent a mastectomy. Her cancer is likely traced to the dangerous factory work she undertook as a young woman struggling to make ends meet and speaks to the very heart of intersectionality — because of her numerous intersections, she took the only work available to her, forced to focus on a measure of immediate security at the expense of a longer, healthier life. At the same time, I think of a unicorn as an inherently fragile creature. Always beautiful and majestic, I always understood them as endangered and in need of protection.

My need to read hope and happy endings into Audre Lorde’s work is more evidence of my own fear of my precarity and of my own death. While I do think hope is at the crux of Lorde’s beliefs, it’s a radical hope that we make an impact and force a change on this world while we inhabit it. One of her most well-known works, “A Litany for Survival,” is heartening in that soothes as much as it emboldens.

Here’s the poem in full:

For those of us who live at the shoreline

standing upon the constant edges of decision

crucial and alone

for those of us who cannot indulge

the passing dreams of choice

who love in doorways coming and going

in the hours between dawns

looking inward and outward

at once before and after

seeking a now that can breed

futures

like bread in our children’s mouths

so their dreams will not reflect

the death of ours;

For those of us

who were imprinted with fear

like a faint line in the center of our foreheads

learning to be afraid with our mother’s milk

for by this weapon

this illusion of some safety to be found

the heavy-footed hoped to silence us

For all of us

this instant and this triumph

We were never meant to survive.

And when the sun rises we are afraid

it might not remain

when the sun sets we are afraid

it might not rise in the morning

when our stomachs are full we are afraid

of indigestion

when our stomachs are empty we are afraid

we may never eat again

when we are loved we are afraid

love will vanish

when we are alone we are afraid

love will never return

and when we speak we are afraid

our words will not be heard

nor welcomed

but when we are silent

we are still afraid.

so it is better to speak

remembering

we were never meant to survive.

What are your interpretations of The Black Unicorn?

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde: June’s Uses of Anger

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde is a monthly analysis of works by queen mother Audre Lorde as they apply to our current political moment. In the spirit of relying on ancestral wisdom, centering QTPOC voices, wellness, and just generally leveling up, we believe that the Lorde has already gifted us with the tools we need for our survival.

Sometimes I think that this is the next time, that the fire is here. It’s been here. It’s simmering beneath our every interaction with doctors, educators, salespeople, people on sidewalks, grocery store clerks, with everybody in every place we go. To be Black is to have your entire life — everything you’ve built, created, cultivated, endured, grown through, experienced, and every fucking thing you’ve attempted to leave behind — hinge on one precarious moment to the next. Even the simple act of naming our oppression puts us in jeopardy — at best, for gaslighting and criticism, and at worst, calls for more police, more guns, more violence, more Black death. The cycle of state violence on Black lives continues and the justifications abound. In speaking of anti-Black hate crimes in the 1980s, Audre Lorde distilled the rationale to: “Because they were dirty and Black and obnoxious and Black and arrogant and Black and poor and Black and Black and Black and Black.”

I’ve had such a hard time gathering myself to write this, largely because so many have done so for centuries, and far better than I could. Lorde did it better than most. But in truth, she is only one of the many Black women, the many queer Black women in particular, who have not only called out the pernicious nature of racism, but have also laid out paths to our collective liberation from it.

In the essay “Apartheid U.S.A.,” Lorde details the horrors of Apartheid-torn South Africa in the 1980s and the damning parallels between that country and her own. She outlines the necessity of solidarity among Black people around the world. As she notes:

“The connections between African and African-Americans, African-Europeans, African-Asians, is real, however dimly seen at times, and we all need to examine without sentimentality or stereotype what the injection of Africanness into the sociopolitical consciousness of the world could mean. We need to join our differences and articulate our particular strengths in the service of our mutual survivals, and against the desperate backlash which attempts to keep that Africanness from altering the very bases of current world power and privilege.”

Lorde’s point about the “desperate backlash” that tries to keep “Africanness” from altering the world’s foundations is particularly evident in so many current collective responses to Black anger. I’m mystified by the frequent emphasis on “peaceful” protests by would-be White allies. As if a protest is ever peaceful. As if the entire point of a protest isn’t disruption. The ease with which people rush to vilify Black people for tearing down the structures, the buildings, and monuments of White supremacy mirrors the hesitancy so many of them exhibit when condemning police for continuing to kill us. It’s so commonplace that some don’t even realize they’re valuing property over human lives; or, rather, they still see us as property, but property worth less than buildings and monuments. As Lorde considers:

“How are we persuaded to participate in our own destruction by maintaining our silences? How is the American public persuaded to accept as natural the fact that at a time when prolonged negotiations can […] terminate an armed confrontation with police outside a white survivalist encampment, a mayor of an American city can order an incendiary device dropped on a house with five children in it and police pin down the occupants until they perish? Yes, African-Americans can still walk the streets of America without passbooks—for the time being.”

Black people in the U.S. are furious right now because we see what is happening. It has happened before and what these uprisings are telling the world is that we will not let it happen again. Institutions will fall; they need to. Racism is itself an institution and the old world order which is built on its face has to go if we are to create and inhabit the sort of equitable world in which Black, queer, and all other marginalized lives can flower. Time and again, Lorde spoke to the need for this sort of global, systemic shift. Her writing in “Apartheid U.S.A.” is no different.

“Like the volcano, which is one form of extreme earth-change, in any revolutionary process there is a period of intensification and a period of explosion. We must become familiar with the requirements and symptoms of each period, and use the differences between them to our mutual advantage, learning and supporting each other’s battles.”

It’s vital we don’t turn away from this moment of Black rage. In this month’s second essay, “The Uses of Anger,” Lorde aptly points out that “anger is an appropriate reaction to racist attitudes, as is fury when the actions arising from those attitudes do not change.” For me, the benefits of embracing my own rage have been twofold: to release my anger has freed me from suppressing it, a key component for the type of self-preservation Lorde has pointed out is a revolutionary act. The other has been to identify my true allies in this fight for Blak liberation.

“But anger expressed and translated into action in the service of our vision and our future is a liberating and strengthening act of clarification, for it is in the painful process of this translation that we identify who are our allies with whom we have grave differences, and who are our genuine enemies.”

Those seeking to police how we express our anger, to only center cis-hetero Black men and negate the acute violence faced by trans Black women, those seeking to downplay our fears with “Not all cops” and “All lives matter,” and even the more insidious inaction of would-be allies who sit stagnant in guilt instead of moving into action—you are part of the problem. Lorde poses this necessary question: “What woman here is so enamoured of her own oppression that she cannot see her heelprint upon another woman’s face?”

For too long, I’ve felt compelled to call on something other than anger, too enmeshed in the respectability politics and Western ideology that treats anger as un-nuanced. But as Lorde reminds us, “anger is loaded with information and energy.” To write it off as uncomplicated or lacking complexity, especially when it comes to Black anger, is to back away from discomfort and from what that anger can teach.

In “The Uses of Anger” Lorde pays special attention to Black women’s anger and the tone policing and disavowals with which it’s so often met. She states:

“For anger between peers births change, not destruction, and the discomfort and sense of loss it often causes is not fatal, but a sign of growth.”

We are in the middle of a revolution. It’s frightening for all the known reasons, but this time is also full of potential. Our Black women’s anger, my Black woman’s anger, is here to signal a necessary sea change. As queer folks, get angry if you’re not already. Understand all of our freedoms are bound up in one another. This final reminder from Lorde is a necessary one about what we should be united against and about the potency of our collective power.

“For it is not the anger of Black women which is dripping down over this globe like a diseased liquid. It is not my anger that launches rockets, spends over sixty thousand dollars a second on missiles and other agents of war and death, slaughters children in cities, stockpiles nerve gas and chemical bombs, sodomizes our daughters and our earth. It is not the anger of Black women which corrodes into blind, dehumanizing power, bent upon the annihilation of us all unless we meet it with what we have, our power to examine and to redefine the terms upon which we will live and work; our power to envision and to reconstruct, anger by painful anger, stone upon heavy stone, a future of pollinating difference and the earth to support our choices.”

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde: May’s Burst of Light

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde is a monthly analysis of works by queen mother Audre Lorde as they apply to our current political moment. In the spirit of relying on ancestral wisdom, centering QTPOC voices, wellness, and just generally leveling up, we believe that the Lorde has already gifted us with the tools we need for our survival.

My Auntie Jean died. My aunt died of cancer and I wasn’t there. No one was, because she died alone in a hospital not even two weeks ago, one day after my uncle and my cousin met with people about moving her to hospice. Two months after she shared her diagnosis with the family, two months and two weeks after the country began sheltering in place.

In some ways it’s surreal to note how little time has passed. I thought I would have more time with her, passed time by bargaining with every higher power I could think of for this storm to pass so I could get home, have time to hold her hand, time to hug her and tell her how much I love her. She was the youngest of three, my grandmother’s baby sister. Now they’re both gone, taken within a five year span that feels simultaneously like an eternity and like each second has eked by, excruciating and slow.

I know I’m far from the only one to mourn from a distance, pre or mid Covid-19. In the midst of trying to wrap our minds around the global pandemic, personal tragedies compete for our presence of mind —both insisting on our full attention, complete with their warring interests. The thing is, cancer is a beast I know. My father faced his first bout of cancer when I was 10, and his second battle continues on today; both grandmothers died of it, too. But to face my aunt’s mortality with the reality of my own, with the risks of what my traveling to her might do — on multiple planes and via multiple airports to be with someone whose immune system was compromised — there’s no clear path to the “right” decision under these conditions.

Out of duty and necessity, I turned to Audre Lorde because, if nothing else, she’s someone who has been teaching me how to face those most painful and raw feelings from which I might otherwise turn away. In writing about her own struggle with metastasized breast cancer in the essay compilation A Burst of Light, she stated she was “Coming to terms with the sadness and the fury. And the curiosity.” I keep returning to that part about curiosity. Probably because I’m a Scorpio, but also because I think curiosity has something to offer us about the fear with which we normally confront death. There’s something otherworldly and ethereal in her ability to always find the light. She writes, “Dear goddess! Face-up again against the renewal of vows. Do not let me die a coward, mother. Nor forget how to sing. Nor forget song is a part of mourning as light is a part of sun.”

The essay is a compilation of journal entries, beginning with the discovery of a mass on her liver and ending with the damning confirmation that the breast cancer she thought was in remission had returned and metastasized throughout her body. Yet even in the midst of a death that was most certainly coming, the only variable was when, Lorde forged a path of her own making. True to form, she acknowledges her ever-present fears and concerns, yet faces them head on.

“There is a persistent and pernicious despair hovering over me constantly that feels physiological, even when my basic mood is quite happy. I don’t understand it, but I do not want to slip or fall into any kind of resignation. I am not going to go gently into anybody’s damn good night!”

My aunt was a doctor, an endocrinologist. A history maker as one of the first Black women physicians to launch a career in our southern, still-segregated hometown. Through it all, even in her last months as she rapidly lost weight and faced symptoms she knew all too well signaled something pernicious and invasive, she kept on with her work. Each time I called or FaceTimed with her I would see piles of charts stacked in the background, a testament to her dedication to her patients, especially as one of the few private doctors to still accept public insurance in Memphis. Even until those last few days before she took her medical leave, she spent over an hour with each patient, making sure she knew each patient’s story so she could best serve them. In many ways it felt like she, too, lived out Lorde’s sentiments:

“[H]ow do I want to live the rest of my life and what am I going to do to insure that I get to do it exactly or as close as possible to how I want that living to be? I want to live the rest of my life, however long or short, with as much sweetness as I can decently manage, loving all the people I love, and doing as much as I can of the work I still have to do. I am going to write fire until it comes out my ears, my eyes, my noseholes — everywhere. Until it’s every breath I breathe. I’m going to go out like a fucking meteor!”

My aunt’s own meteoric impact on my life means that I feel her loss on every plane — psychic, emotional, and physical. This, on top of the losses we are all experiencing as we continue to tread through our new quicksand reality, has left me fighting every impulse to close in on myself. There’s just so much to feel that even trying to parse through individual emotions is labor. But even when I’m ready and willing to stay mired in my fog, Lorde’s work arrives with a timing that is as prescient as ever. She writes:

“How do I hold faith with sun in a sunless place? It is so hard not to counter this despair with a refusal to see. But I have to stay open and filtering no matter what’s coming at me, because that arms me in a particularly Black woman’s way. When I’m open, I’m also less despairing. The more clearly I see what I’m up against, the more able I am to fight this process going on in my body that they’re calling liver cancer. And I am determined to fight it even when I am not sure of the terms of the battle nor the face of victory.”

In the end I chose not to fly home for the funeral. I watched the service and smiled through tears of grief and fear as I saw my family members gathered for the homegoing of one of our own. Tennessee is one of the states beginning to slowly re-open businesses, meaning the funeral home could host up to 100 people for the service. As painful as it was not to be there, the potential exposure my travels could bring to such a large crowd was a risk I just simply couldn’t take. In reading A Burst of Light in the days before and after the funeral, my resolve was strengthened by the following:

“It is the bread of art and the water of my spiritual life that remind me always to reach for what is highest within my capacities and in my demands of myself and others. Not for what is perfect but for what is the best possible. And I orchestrate my daily anticancer campaign with an intensity intrinsic to who I am, the intensity of making a poem. It is the same intensity with which I experience poetry, a student’s first breakthrough, the loving energy of women I do not even know, the posted photograph of a sunrise taken from my winter dawn window, the intensity of loving.”

I know it’s a common aphorism to say that grief is love with no place to go, but I do think there’s truth to that. In the midst of my personal grief, this moment and Lorde’s words are teaching me that what so many of us are grieving is the loss of a life that we knew how to live. What’s replaced that life for so many is a way of existing, not necessarily living. These last few days without my aunt feel almost identical to the first few days without my grandmother — I didn’t know how to live in a world where she wasn’t present. Lorde, of course, offers a remedy for these feelings:

“I make, demand, translate satisfactions out of every ray of sunlight, scrap of bright cloth, beautiful sound, delicious smell that comes my way, out of every sincere smile and good wish. They are discreet bits of ammunition in my arsenal against despair.”

So often I get swept up in the beauty of her writing that I become frustrated when it comes to trying to enact her words. There’s a cleanness I’m craving that I know isn’t possible, but I still want it. I can’t think of a way to make it okay that she’s dead. Nor is it okay that there is no end in sight for our current circumstances, no neat and easy way through this unprecedented time. Any sort of resolution won’t happen this year or maybe even the next, and the implications of that are indeed those of life and death. But Lorde, in this unflinching look at the disease she knows will take her life, offers a window into her learning not only how to cope, but how to make the absolute most of all she still has. She says:

“How has everyday living changed for me with the advent of a second cancer? I move through a terrible and invigorating savor of now — a visceral awareness of the passage of time, with its nightmare and its energy. No more long-term loans, extended payments, twenty-year plans. Pay my debts. Call the tickets in, the charges, the emotional IOU’s. Now is the time, if ever, once and for all, to alter the patterns of isolation. […] I am not ashamed to let my friends know I need their collective spirit—not to make me live forever, but rather to help me move through the life I have. But I refuse to spend the rest of that life mourning what I do not have. If living as a poet — living on the front lines — has ever had meaning, it has meaning now. Living a self-conscious life, vulnerability as armor.”

How are you finding ways to cope with any feelings of loss or despair? Please drop some wisdom, encouragement, and love in the comments.

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde: April’s Arithmetics of Distance

Year of Our (Audre) Lorde is a monthly analysis of works by queen mother Audre Lorde as they apply to our current political moment. In the spirit of relying on ancestral wisdom, centering QTPOC voices, wellness, and just generally leveling up, we believe that the Lorde has already gifted us with the tools we need for our survival.

This is dedicated to those who are just trying to make it through every day. Those peeling themselves out of bed, climbing uphill through daily tasks, Zoom catch-ups, and yet another day of being indoors. This month’s entry is not a call to action, but instead it’s a balm, a reminder that among the many things we must classify as essential, poetry is essential too. Last month, when I decided to focus on “Poetry is Not a Luxury,” it wasn’t in anticipation of all we might distance ourselves from, but rather because poetry can sustain us through each and every one of our circumstances.

We now find ourselves living in an era of indefinite social distancing, a phrase new to most people that’s become part of our everyday vocabulary. A way of neatly summing up the necessary actions and inactions we must take as a measure of care, and as part of a global community. Social distancing often feels like a series of “don’t”s that organize where we go and with whom we interact. Faced with an unprecedented global pandemic, many seem to find themselves spurred to action in a crisis, feeling the urge to do, to move. But as my partner recently said to me, being still is also an action.

It’s been gratifying on an almost cellular level to find that queen mother Audre Lorde can so frequently speak to the times and the places in which we find ourselves. Her final book of poetry, The Marvelous Arithmetics of Distance, is no exception. Penned from 1987 to 1992, The Marvelous Arithmetics of Distance emerged in Lorde’s last years as she contended with metastasized breast cancer that would ultimately end her life in November 1992. With those years spent between Berlin, St. Croix, and the United States as Lorde traveled, taught, and sought treatments for her cancer, each poem visits themes of death, family, desire, and womanhood.

In an interview from Berlin, Lorde said she wrote The Marvelous Arithmetics because she didn’t expect she would have another book. She said upon reviewing her journals and collections, “ there was a shape that was emerging. And it was exactly that, of […] how difference alters, in other words, how perspective alters the ways in which you perceive difference. From place to place.” She goes on to explain that she chose to call this process “arithmetics” because arithmetic comprises “the basic ways in which you combine numbers. I want to talk about the basic ways that distance alters the way we see. Mathematics frequently deals with theoretical relationships. But arithmetic deals with a kind of pragmatic actuality.”

Audre Lorde said 🗣 Stay In The House

For those who are like me — who have found the abrupt distancing from family, from friends, from loved ones, from sources of income and other forms of support to be overwhelming and isolating — let Lorde’s message soothe and embolden you. Even while facing certain death and the uncertainty of what comes after, Lorde lived what she wrote, confronting the fullness of her emotions and experiences to poetically transform them into something beautiful and healing.

Rushing headlong / into new silence / your face / dips on my horizon / the name / of a cherished dream / riding my anchor / one sweet season / to cast off / on another voyage / No reckoning allowed / save the marvelous arithmetics / of distance (from “Smelling the Wind”)

I love those last two lines about reckoning and distance. I think this is Lorde’s acknowledgement of the pain of any sort of rupture. Here I think to the platitudes offered when people don’t know what else to say in the face of pain: “This too shall pass.” Or, “time heals all wounds.” Rather than looking beyond the pain of the rupture, rather than looking into a future that resembles something we consider normal, Lorde asks us to consider what this rupture can teach us. How we might settle into the discomfort of distance.

There is a timbre of voice / that comes from not being heard / and knowing you are not being / heard noticed only / by others not heard / for the same reason. / The flavor of midnight fruit tongue / calling your body through dark light / piercing the allure of safety / ripping the glitter of silence / around you / dazzle me with color / and perhaps I won’t notice / till after you’re gone / your hot grain smell tattooed / into each new poem resonant / beyond escape I am listening / in that fine space / between desire and always / the grave stillness / before choice. (From “Echoes”)

When I first read this poem I thought that surely Lorde was referencing the voices of marginalized folks who too often go unheard, often brought together by our shared experiences of being ignored. And while this may be true, further readings got me thinking that these verses could also be read as a confrontation with one’s self, with one’s unspoken or unacknowledged desires.

One thing that has become apparent to me in the midst of this pandemic is that so many people are uncomfortable being alone with themselves. Distance in this case is the space they put between themselves and the mirror, clinging to whatever can provide the “allure of safety.” The poem’s sexual and sensual overtones are apparent, but I wonder if what is also at play is the choice between giving into those desires or making a more difficult, less safe choice of facing that which has gone unheard, perhaps within one’s own mind.

Through the core of me / a fine rigged wire / upon which pain will not falter / nor predict / I was no stranger to this arena / at high noon / beyond was not an enemy to be avoided / but a challenge / against which my neck grew strong / against which my metal struck / and I rang like fire in the sun.

I still patrol that line / sword drawn / lighting red-glazed candles of petition / along the scar / the surest way of knowing death is a fractured border / through the center of my days. (from “The Night Blooming Jasmine”)

This is yet another example of how Lorde’s living aligned so seamlessly with her writing. While Lorde speaks explicitly to her terminal cancer here, pain is no foreign concept to her as a Black lesbian woman and mother. For many of us, too, this pandemic hasn’t necessarily borne new pains as much as it has reopened old wounds. The feelings of loss, isolation, depression, and more that many of us are now facing aren’t theoretical or buried in some far-off past; they are proximal and constant.