In the Face of Government Neglect, Trans Leaders Spearhead Housing Solutions

There’s no place like it. A shelter from storms. Not a place, but a feeling. We’ve all heard those inspirational quotes about home — what it should feel like. For trans people, finding home can feel like leaping through hoops of systemic transphobia, sexism and racism to access and maintain safe and affordable accommodation.

It’s common knowledge that institutions already target trans people with housing discrimination. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development proposed a rule in July that allows homeless shelters to deny transgender people access to single-sex shelters. As detailed by the National Center for Transgender Equality, one in five transgender people in the U.S. has been discriminated against when seeking a home, and more than one in ten have been evicted from their homes because of their gender identity. In Louisiana, one in three trans people report experiencing homelessness at some point in their lives.

Whilst governments fail, Black trans organizers excel. In the South, initiatives like the House of Tulip address the housing crisis for trans people. Based in New Orleans, Mariah Moore and Milan Nicole Sherry founded House of Tulip after launching an online fundraiser to build a long-term, more sustainable solution to housing for trans and gender non-conforming people.

The fundraiser went beyond the initial goal of raising $400,000, allowing House of Tulip, also referred to as Trans United Leading Intersectional Progress, to close on a property they will restore into four different units and offer to trans and gender nonconforming people in the city of New Orleans. Mariah and Milan have partnered with a general contractor and architects, and are looking into organizational management. They have also begun searching for more land to purchase as further additions to their land trust model.

The founders circle of House of Tulip. Via their Instagram.

Over 7,000 people donated to the community land trust that supports Black trans leadership and Black trans futures. “It takes organizations a lot longer to build this momentum. Being able to do it so quickly speaks volumes about the fact that people really understand and know that housing for trans people is really needed,” Mariah said.

The majority Black and women-led collective could achieve not just land justice but also autonomy within their physical spaces — especially in this era of lockdowns, quarantines, and social distancing. Owning land gives people the right to grow their own crops or simply be outside. House of Tulip’s long-term housing solutions include citywide benefits such as creating safeguards around exclusionary development and gentrification, as well as paths to homeownership. “I envision smaller land purchases with decently sized homes on them that our community members actually own so that their pathway to homeownership is a reality,” said Mariah.

Mariah’s work at the House of Tulip remains grounded in the women and kin that got her this far: “I was shown so many examples of strength and resilience modeled by fierce, brilliant, brave women around me who were sex workers. They taught me that my life was still valuable, I still deserved respect and humanity. I think about all of the times they showed up for me and helped guide me – they’re part of the movement.”

Anti-trans rules and policies introduced by the U.S. administration is accompanied by a hostile culture against trans people. The current epidemic of murders — with many recent cases in the South, including Shaki Peters and Queasha D. Hardy in Louisiana and Jazzaline Ware in Tennessee — paints a bleak picture of the violence trans people continue to face and the adversity that needs to be challenged.

Mariah is not alone in creating optimism and hope for the trans community. Award-winning activist Kayla Gore founded My Sistah’s House with Ellyahnna C. Wattshall in 2016, intending to bridge the gap in services for trans and queer people of color in Memphis, Tennessee. That year, there were only 71 beds available in emergency shelters across the Memphis metro area and none of them were designated as trans-specific. Federal guidelines for these shelters don’t protect trans people. In response to the city’s lack of emergency housing and a steady decline in Black homeownership rates, My Sistah’s House provides both emergency shelter and now stable mortgage-free housing to trans people of color.

Members of My Sistah’s House visits a supplier of tiny homes. Via the GoFundMe page of My Sistah’s House.

Kayla originally converted her six-bedroom house into an emergency housing facility with eight beds available for queer and trans people in need of shelter. “Housing equals safety [and the] violence that we face happens in the street more often than at home,” she wrote on the My Sistah’s House website.

Now, Kayla and Ellyahnna are raising money to build tiny homes to house trans women of color who are at higher risk of violence and discrimination when attempting to access housing in Memphis. With each home costing $13,000, they’ve been able to fundraise to build 20 micro-houses and create a neighbourhood on almost 30 acres of land they’ve purchased. They’ve received support from volunteers who have helped to build the homes. The pair plan to create community gardens in addition to housing and recreation spaces spread throughout underserved communities with any additional funds.

In a moment like this, there is so much work going into mutual aid for more vulnerable communities. As we shield ourselves in our respective homes, many of us are able to donate with a click of the mouse or share with a few taps on a smartphone. Will these fundraisers appear on our timelines when the pandemic wanes? Kayla writes on the Tiny Homes fundraiser, “Share not only our fundraisers after violence or death; share the tiring work of Black and browns [sic] trans men, women, and my Fam that said fuck all that shit!”

Black trans people have yet to fully benefit from their involvement in liberation and activism, even in movements committed to leaving no one behind. The leadership of Black trans folks like Marsha P. Johnson and Miss Major Griffin-Gracy is finally being recognized as transformative. “It’s because of Black TGNC people that LGBTQ people remain closer to freedom,” Mariah reminds us.

In our wildest dreams, what would it feel like for trans people to have full freedom within housing? Things feel more vivid — brighter, lighter and promising. Vivid because there are possibilities of homes for generations to come. Thriving neighborhoods full of joyful trans folks, free from policing, violence and risk of homelessness, the heavy burdens and fears no longer weighing us down. Neighbourhoods abundant in interdependence and mutual care — the feeling of being at home in this world.

Share and donate to House of Tulip or My Sistah’s House to help fund housing for Black and brown trans and gender nonconforming people.

Europe’s CuTie.BIPoC Festival Is a Life Raft in the Sea of Whiteness

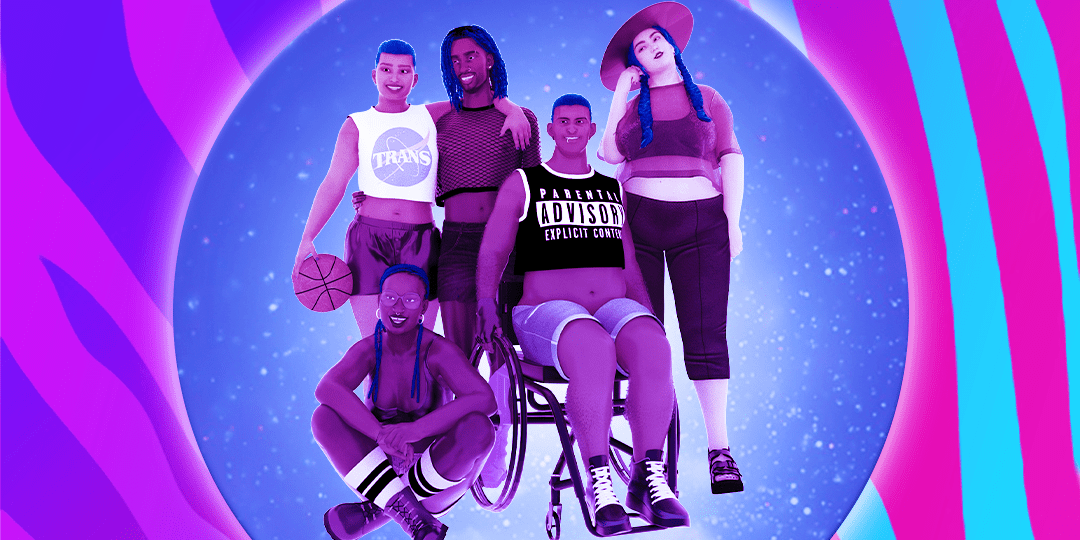

Illustrations by ddnebula

The creation of Queer, Trans, Intersex, Black, Indigenous, People of Color (QTIBIPOC) spaces are crucial for many folks, who don’t always feel like they can be their full selves in white queer communities.

CuTie.BIPoC Fest is a grassroots organization that provides an alternative space for QTIBIPOC in Western Europe. All but one of their weekend events, which took place in Copenhagen, have been held in Berlin and this year will be the Festival’s fifth year. The The groundbreaking events they throw are self-organized and meant to give a platform to groups that are typically marginalized, even in gay and queer communities. In light of COVID-19, CuTie.BIPoC Fest are currently planning to hold a festival online, remaining largely community and volunteer driven.

I made some of my closest friends through non-white non-club centric spaces, like CuTie.BIPoC Fest, where there was sober space to explore myself as a Black and Asian person navigating the world. I sat next to them in workshops, in small circles I joined during lunch and connected with them through social media before my first festival. These connections flourished after I’d fly home — one-on-one as they travelled to London for a weekend or I went to Berlin for a few days. It’s often after CuTie.BIPoC finishes that I miss the abundance of BIPOC people, safety, community and learning. I wanted to know what CuTie.BIPoC meant to other attendees and spoke with four of them; Elliott, Layana, Dera and Aubrey* (*name has been changed). These cuties shared QTIBIPOC joy, the slippery slope of organizing in a capitalist and white supremacist system and their hopes for QTIBIPOC futures.

Layana is a 34-year-old Berliner who identifies as a Black, queer femme. Elliott describes himself as a trans, non-binary, queer Anatolian from the states and has been living in Berlin. Aubrey grew up in a predominantly white populated area in Northern Germany until moving to Berlin at 20, and identifies as Black and genderqueer. Dera is a 25-year-old, queer, first-generation, Nigerian-American, who grew up in the U.S. and moved to Berlin in the summer of 2018 — the same summer as their first fest. “I actually heard about the festival through you before I even moved to Berlin!” Dera reminds me.

CuTie.BIPoC Fest “can be a life raft in the sea of whiteness” among the queer, artist and sober communities Elliott participates in. In fact, as queer people of color, it’s rare to find a space that feels “safe enough” and that’s the all-encompassing reason and beauty behind the festival. As QTIBIPOC, the festival explains online “we often experience that certain aspects of our identities are separated. Within queer spaces only our queerness is in focus, in a way that erases our BIPOC experiences. The same happens in BIPOC communities, where our queerness is not always acknowledged. This is why this dedicated space is so important.” Their hope is to create a space where complex identities can flourish through community building, and create a space for people to address issues that affect us and our communities.

One of the more refreshing and radical aspects of CuTie.BIPoC Fest is that it operates at a grassroots “DIY/DIT” community level, meaning that unlike a conference, everybody chips in and is responsible for the organizing of the festival. What’s more, the program is decided by attendees and there is also scope for spontaneous activities during the open spaces of the program. In the past, these open spaces have been filled with conversations on colorism, interracial dating and creative workshops like comic drawing. he folks I interviewed had attended dancing workshops, sessions about gender, and Dera, in particular, really liked the Queer Futures zine-making workshop.

Dera believes what makes the festival different to similar programmed events is its financial accessibility. The event depends on time, money and community collaboration to help things run smoothly; cooking, childcare, cleaning and setting up is handled collectively by volunteers. Layana feels it’s important to volunteer her time at the festival each year and the last time Elliott attended the festival, he participated in the food crew, creating healthy low-cost meals for up to 100 people each day.

CuTie.BIPoC Fest exists for people like Dera, Elliott, Layana and Aubrey, but what does it mean to them and their identities? For Layana, CuTie.BIPoC Fest means something to seriously look forward to all year long. “I look forward to space to breathe! Space to be! Space to heal! It means feeling seen, and meeting people eye to eye. It means finally feeling desirable and beautiful. It means getting to see myself in people. Safely sharing culture. Learning, growing, healing, feeling.” Similarly, for Dera, CuTie.BIPoC Fest is the most important organized Pride celebration of the summer for them. “CSD (Berlin’s Gay Pride) weekend does not feel like a space meant for me and other QTPOC. Would you believe that Big Freedia was the main act at CSD 2018, and the crowd wasn’t even dancing? For shame.”

“I look forward to space to breathe! Space to be! Space to heal! It means feeling seen, and meeting people eye to eye. It means finally feeling desirable and beautiful. It means getting to see myself in people. Safely sharing culture. Learning, growing, healing, feeling.”

For Elliott, It means there is a space where he can break out of an overwhelmingly white community, “A place where I don’t feel compelled to explain or apologize for my existence as much.” A few days before attending the first festival, Aubrey ended a relationship with a white cis-man and the festival helped them acknowledging their own queerness. They attended a workshop on dating white people and felt glad to hear others had a history or were still in relationships with white cis-men or white cis-het men because that was always something that made Aubrey feel not queer enough. “I feel my heart expanding when I think of that festival and how I developed afterwards.” Aubrey feels the festival gave them confidence for everyday life and assurance that there is a place where they explore who they are. “I feel so grateful.”

CuTie.BIPoC Fest created a space where BIPOC people can feel at home in their queerness, especially in a European context, but it does not come without its downfalls. Aubrey says, “like the outside world, a lot of the labor and damage control falls on the shoulders of dark-skinned femmes.” Layana agrees, “There is an essential need for a space like this and it’s often the dedication of femmes who are the people organizing. There are less people able/willing to organize and not enough funds to pay the organizers accordingly.” This kind of cycle means the festival is insecure not only financially but organizers face the risk of burning out each year as they carry out the brunt of the work for free. Despite this, Layana plans to attend more festivals in the future and continue to volunteer her time — the joy and healing created here is vital to her.

So much of our Western world is rooted in anti-Blackness and femmephobia, even in the spaces we are trying to build anti-structure, and that rings true when Elliott notes, “There are things that disappoint me about the festival, but no more than any event.” Creating a safe space for QTIBIPOC people doesn’t always mean accessibility and inclusion are 10/10, but the festival tries to be communicative. They recently released a document outlining their shortcomings, showing accountability and transparency. When asked what he would improve about anti-structural organizing so that Black people, especially feminized Black bodies, don’t have to navigate spaces created for them the same ways they navigate “real world” spaces, Elliott says, “we can un-build the patriarchal and capitalist structures that we face in other parts of our lives, but we must replace them with something else. We can develop softer structures, fleshy and viscous, which expand and support and equalize. For example, in a roundtable discussion the louder or more extroverted people will be heard and those who are introverted or slower to raise a hand, or have anxiety or need time to translate their thoughts, will remain buried in an anti-structure.”

“We can develop softer structures, fleshy and viscous, which expand and support and equalize.”

There are many pros to organizing at capacities like this and reasons I hope CuTie.BIPoC Fest continues to thrive and create an alternative space for queer people of color. Unfortunately, issues of anti-Blackness, patriarchy and capitalism, even within spaces that are supposed to be inclusive, reflect issues in our larger movements. We need to continue to do the work to do better because LGBTQ, BIPOC and intersectional organizing still crumbles under ingrained structural oppression. I tip my hat to CuTie.BIPoC Fest’s attendees and organizing committee for attempting to build their space with care and community. The complexity of queer and trans lives of color, not just in NGO spaces or charities, but in spaces that we are trying to build for ourselves, still holds the same narratives and ideals created by the Colonial West. It’s often hard to escape what’s so ingrained in us, even when we create spaces to end it. But we prevail.

Even amongst these structural and mindset hurdles, CuTie.BIPoC Fest has brought a sense of joy and hope to the folks I interviewed. Aubrey spontaneously facilitated a singing circle at their second festival because many people had mentioned they would love to sing, but thought they couldn’t or didn’t find a safe enough space to explore their voices. “This was probably one of the most touching moments for me because I witnessed people being super shy about their voice singing alone in front of the group and people jamming and freestyling together, when before, almost everyone said that they couldn’t sing – liars!”

Dera appreciates that something like CuTie.BIPoC Fest happens so close to CSD because they still get to participate in Pride celebrations without feeling like an outsider at an event that’s supposedly celebrating people like them. The literal unbearable whiteness of Pride is the best reason why festivals like CuTie.BIPoC Fest exist. There are barely any BIPOC exclusive spaces in Berlin, and for Layana, this is the “safest, happiest and most fun space” she has ever experienced.

“It feels so different to feel the energy in those spaces,” Aubrey notes. “I open up, I am more loving, I feel love surround me and move through me. I feel magic and potential. I feel potential expanding. I feel fire and life; I feel people come to life and I feel myself come alive.” Aubrey is able to sit with loved ones in an open space and not have to worry about people sharing their opinion on their appearance, staring, making strange or rude comments – “That’s amazing.” Dera agrees, “It’s rare that I see as many QTIBIPOC in one place in Berlin as I do when I’m at CuTie.BIPoC Fest. To me, the best thing about the festival is being surrounded by so many melanated and queer people. The energy is amazing. Not to mention that they are *ahem* very attractive people. I met my girlfriend because of this festival.”

During this uncertain moment, how will we continue to build accessible QTIBIPOC communities? Layana continuously will speak up and address injustices she sees come up within our community such as anti-Blackness and femmephobia. “In the future I hope I will have more capacity to become a bigger part of the organization of this festival and would love to offer workshops within my expertise in the future.”

Elliott is keen on creating a health and wellness conference for QTIBIPOC. “I think it is always important to have space for ongoing conversations around medical trauma, breaking through shame, self-healing, ancestral knowledge, the connection between emotional and physical health, accessible plants and herbs, and general access to medicine and healthcare for QTIBIPOCs. I don’t know that this will happen any time soon, but wow. Wouldn’t that be amazing?” Aubrey plans to be more involved in music and host healing circles. “It is so difficult to find access to spaces that can facilitate healing for us. Either it is super expensive or so white-washed that most of the time I’m busy regulating my uncomfortableness with whiteness and cisness and heteroness that I cannot focus on what I actually need. And I believe that all the discrimination is a destruction of our body, mind, soul and spirit. And that makes us forget that we are actually pretty great.”

It’s a space that, even with imperfections, is missed by the people I spoke to — especially during this time of social distancing. Elliott, who’s expecting a baby anytime soon, feels that even in this era of social distance, protests, and policy reform, they need to connect with their QTIBIPOC community even more. “CuTie.BIPoC provides a subtle and powerful act of collective feeling,” he says, and while our white friends are talking about how the world is suddenly a scary place, where institutional inequalities are a death sentence, QTIBIPOC people have been with this knowledge for centuries. CuTie.BIPoC Fest gives me hope that it’s possible for spaces to exist that don’t sit under a roof of white supremacy, patriarchy or capitalism, but for that to happen the work must continue in all corners of our community, even when we think we are doing our best.

Black Trans People Have Been Modeling Mutual Aid Before It Became a Buzzword

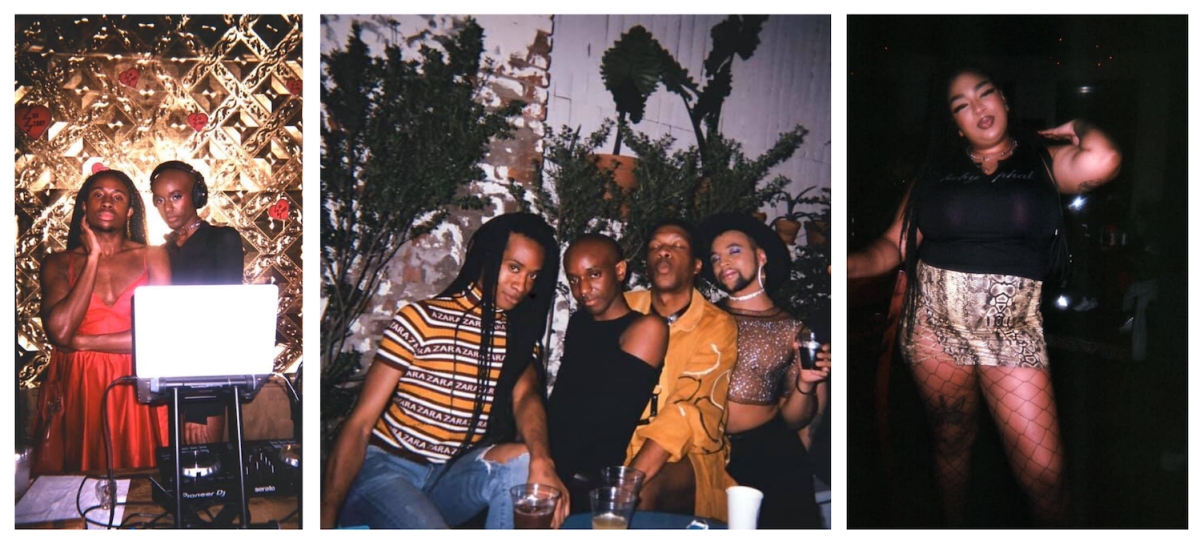

In the absence of infrastructure afforded to the support of white and straight communities, Black trans communities have been supporting one another historically. One example, “For the Gworls” has been raising money through rent parties since before “mutual aid” became a buzzword.

When Black trans organizer and founder, Asanni Armon, moved to New York three years ago, friends plugged them into the Black queer scene through organizing collectives like the Black Youth Project. It was through organizing and accessing Black party spaces that Armon, also an up and coming rapper, built community and launched For the Gworls. “Many venues in New York have said no to hosting us for fear there will be a low turnout” Armon says, but parties are busy and thriving with Black joy. Through the doors to For the Gworls, attendees are vogueing to hip hop, R&B, techno, house and afrobeats centered and geared toward Black people and Black trans people in particular. “For anyone who’s experienced New York City’s Black queer party culture, this is no exception.”

Money raised by For the Gworls goes towards paying for someone’s rent, another person’s gender-affirming surgery and any leftover funds are donated to similar mutual aids for Black communities. Their first party in August 2019, raised $1575 for two Black trans femmes. A month later, their rent party aimed to fundraise for three Black trans folks raised $2500 of the $3300 goal; $1500 of that at the door alone.

Whilst the closure of non-essential businesses and a lockdown in response to COVID-19 has meant an end to rent parties and in person fundraising, a new online medical fund has been created in response to the effects of the government lockdown on Black trans people. For the Gworls Medical Fund provides assistance to Black trans folks who need to travel via rideshare to and from medical facilities or are in need of co-pay assistance for prescriptions and (virtual) office visits.

Acts of community care as far back as the late 20th century have existed for Black trans people. For example, the Black house mothers who housed their children and built chosen families from scratch in response to a lack of role models and support systems for queer and trans people of colour. One of the most notable examples of mutual aid amongst Black communities came from the Black Panthers, who provided free breakfast and health programs for organizers.

Before COVID-19, trans people were already four times as likely to be out of work and right now 21.5 million people who are documented to work remain unemployed in the U.S. Job insecurity amongst Black trans people is likely to continue at high rates — funds and initiatives like For the Gworls demonstrate the resilience that Black and trans communities have now and have had historically in the face of a sheer lack of resources and access to resources. This denial of resources happens not only through transphobia, but through racism and colorism.

Job insecurity amongst Black trans people is likely to continue at high rates — funds and initiatives like For the Gworls demonstrate the resilience that Black and trans communities have.

Being an organizer who now has to fundraise online, doing so through social media can be a double-edged sword for Armon; “I try not to look at social media; I try not to see videos of protestors beat up; unplugging when I can helps me take care of myself.” Armon believes self-care is key; “I used to work out and go for walks, then the virus hit. I’m in touch with my spirituality and talking with my friends and my ancestors. I try to engage with them as much as possible because the community can be lifesaving.”

Anti-Blackness and transphobia have shown up in instances of police brutality, often ending in the loss of Black trans lives, amidst the nation’s outrage and “an epidemic of violence against trans women of color” – before and after the murder of George Floyd:

- Nina Pop, a 28-year-old Black trans woman found stabbed to death in her apartment in Missouri early last month.

- Tony McDade, a 38-year-old Black trans man fatally shot by police in Tallahassee, Florida.

- Iyanna Dior, a 21-year-old Black trans woman beaten by 20 men whilst all but one onlooker stood by and watched; Dior managed to escape further violence.

- Riah Milton, a 25-year-old Black trans woman shot and killed during a robbery attempt in Liberty Township, Ohio.

- Dominique “Rem’mie” Fells, a 27-year-old Black trans woman whose dismembered body was found in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

McDade is the 12th documented case of trans people killed in the U.S. this year and since then, the number has risen to 15 documented cases. Last year, 26 trans people were killed in the U.S. and of those 26, 91% were Black women.

Black people, femmes especially, do a lot of the work behind the scenes within activism and organizing. It’s no secret that The Black Lives Matter movement was started by three Black women (Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi) in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer, George Zimmerman but there is still work to be done that accounts for all Black lives. Breonna Taylor’s murderers still remain free and names like Mya Hall, Tamir Rice, Tanisha Anderson, Walter Scott and Sandra Bland are fundamentally important in our need for justice.

Justice for McDade, who was initially misgendered in coverage of the fatal shooting by police, remains left out of many people’s advocacy. The same night as the Stonewall protest, Black Trans Protestors Emergency Fund was launched. “There was a need to make this fund because everybody was talking about George Floyd, but before we had the murder of Nina Pop and recently the beating of Iyanna Dior.”

“There was a need to make this fund because everybody was talking about George Floyd, but before we had the murder of Nina Pop and recently the beating of Iyanna Dior.”

In response to Black Lives Matter protests, For the Gworls partnered with Black Trans Travel Fund, The Okra Project and The Black Trans Femmes in the Arts collective for “The Black Trans Protesters Emergency Fund.” This fund was born through a group chat between the four groups discussing what they each did; For the Gworls covered rent and gender affirming surgery, Okra covered food insecurity and now health resources and rent in response to COVID-19 and Black Trans Travel Fund covered travel for Black trans women to appointments.

Given that so much media featuring Black trans femmes is about trauma, there’s something to be said about For the Gworls cultivating Black trans joy, community and liberation through their initial rent parties. Yet, whilst there is hope for and work towards Black liberation, for Armon, full Black liberation does not seem possible in their lifetime. “When we finally eradicate white supremacy, we still have to do the work of local education to talk about how we need to work within Black communities and how Black people can respect each other.” Armon refers here to gender, sexuality and disability — these labels, layered with Blackness, create additional struggles that Black people can face under colonialist government, culture, society and institutions.

When asked what non-Black people can do for Black communities beyond donating to these funds; “Have conversations about this with other non-Black people in your community,” Armon suggests, “We get lost in different campaigns and issues and the idea of ‘if I just share it I’ve done my work for the day,’ but nothing is more effective than in person communication. Sharing is great, but messaging people directly about these stories and systemic issues as a means to donate to a cause like this is better.”

You can donate to each of the fund mentioned through the links below:

For the Gworls

Black Trans Travel Fund

The Okra Project

The Black Trans Protesters Emergency Fund