0. 1/28/2012 – Art Attack Call for Submissions, by Riese

1. 2/1/2012 – Art Attack Gallery: 100 Queer Woman Artists In Your Face, by The Team

2. 2/3/2012 – Judy Chicago, by Lindsay

3. 2/7/2012 – Gran Fury, by Rachel

4. 2/7/2012 – Diane Arbus, by MJ

5. 2/8/2012 – Laurel Nakadate, by Lemon

6. 2/9/2012 – 10 Websites For Looking At Pictures All Day, by Riese

7. 2/10/2012 – LTTR, by Jessica G.

8. 2/13/2012 – Hide/Seek, by Danielle

9. 2/15/2012 – Spotlight: Simone Meltesen, by Laneia

10. 2/15/2012 – Ivana, by Crystal

11. 2/15/2012 – Gluck, by Jennifer Thompson

12. 2/16/2012 – Jean-Michel Basquiat, by Gabrielle

13. 2/20/2012 – Yoko Ono, by Carmen

14. 2/20/2012 – Zanele Muholi, by Jamie

15. 2/20/2012 – The Malaya Project, by Whitney

![]()

I have difficult parents — they’re immigrants and I’m first-generation, American-born. They are also traditional and very homophobic, and that has not made my life easy. I knew in my single digits that I was gay, but I had nowhere to go with that knowledge, and no one to talk to about it. I looked online for people to connect to, but this was pre-YouTube, so it took half a day on our dial-up connection to download 30-second clips from The L Word or Boys Don’t Cry. I looked for queer people on Xanga to talk to, but that community wasn’t the kind I needed. What I really needed was someone to talk to, and someone to look up to, who understood what I was going through — race-related issues and all.

Gregory Pacificar and Deney Tuazon also had this problem. It’s strangely comforting knowing that we experienced the same isolation as queer people of color, and that we all looked for the same difficult-to-find queer community. Pacificar and Tuazon similarly went to the Internet to look for queer Filipinos to talk to, and they weren’t able to find that community, either. As Pacificar says, “There was a lack of our visibility but there wasn’t a lack of porn sites.”

Pacificar and Tuazon started talking to people involved with Barangay LA, a not-for-profit organization that supports the LGBTQ Filipino/a-American community in Los Angeles, asking other queer Filipinos/as what their coming-out stories were. “A lot of them talked about their family, being afraid to tell others, and soon a story started to develop,” Pacificar says. “We started to see commonalities in their stories, and in our own as well.”

Pacificar explained that the people they talked to also described a desire to find others who “were just like them” when they were first coming to terms with their sexualities. Other queer Filipinos/as found chat rooms to connect with people (“AOL was big when we were coming out,” Tuazon adds), but the lack of visibility still remained. “They [still] couldn’t find positive images of other LGBTQA Filipinos/as,” Pacificar says.

Out of this absence came The Malaya Project.

According to Pacificar, The Malaya Project, in collaboration with Barangay LA, collects “written and photographic narratives of the lives of proud LGBTQA Filipinos and Filipinas.” The word “Malaya” means “to be free,” and these images are truly liberating — how often do you see queer people of color feeling proud of themselves, doing well for themselves, and fighting for themselves?

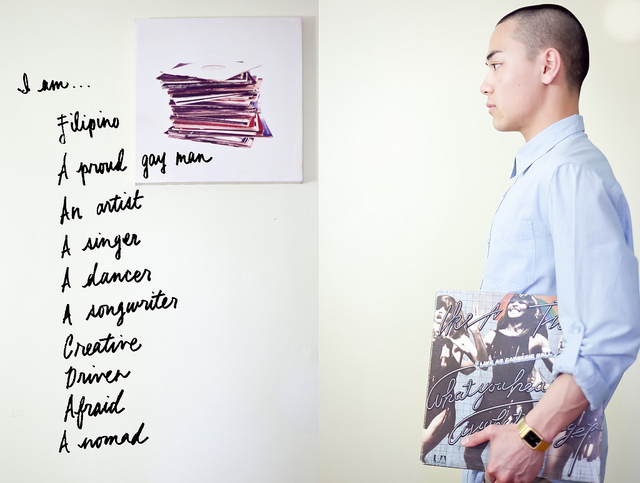

When I firstsaw the images, I was struck at how infrequently I’ve seen images like that of queer Filipina artist Allison Santos (of That’s What She Said) smiling and laughing with her family inside of a modest backyard LA garden. Or musician and singer Jonathan Atanaya Ilano standing in his home space, holding a vinyl copy of Ike and Tina Turner’s What You Hear Is What You Get. Or Patrick Santa Ana, a designer, standing proudly in the rooms of the accessory store he opened in Long Beach, CA, ELEV8. Or Maria Carmen Hinayon, a pageant-winner and student who identifies as “transgender and empowered,” walking proudly through her school’s campus.

“For me, [The Malaya Project] was a chance to give someone an opportunity to look up to someone when they’re a teen. A chance I didn’t have,” Pacificar says. “I was one of those gay boys looking for a role model, looking for guidance.”

The images are both powerful and empowering. Not only do they present the individuals in their personal space, but the photos capture the details of their subjects’ lives, from the contents of Hinayon’s purse (lip gloss, perfume, brushes, sunglasses and a makeup compact) to the array of shoes (slip-ons and lace-ups covered in everything from plaid to black leather) lined up in a wall in Ilano’s home. It’s these details that create a complete and complex picture of identity. Pacificar, a filmmaker, and Tuazon, a photographer, clearly treat their subjects with care and compassion.

“Their story is what starts the creative process,” Tuazon says. “We always ask our subjects what it is that they want to share to others.”

Each of the profiles highlights something particular to each of the individuals — in Ilano’s case, this particular spark “was music and it was natural to highlight that side of him,” Tuazon adds. Ilano’s profile is one of the two that includes video, in which he belts out a song he wrote himself “when he was trying to figure out who he was as a gay teen,” says Pacificar. “When he showed us his lyrics we just had to capture him singing the very song he wrote to get through his teen years.”

The lyrics are heartfelt and emotional: “Year after year / growing into this fear / Kept me hoping / I’d make it to the other side / Year after year / drowned myself in my tears / but now I’m here / on the other side.” It’s the kind of thing a queer kid needs to hear, whether she’s a person of color or not.

[yframe url=’https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2IzhCG2JAvY’]

Hinayon’s message is similar. In one image, Hinayon walks stoically through campus, and in her handwriting she writes about being “bullied, harassed and discriminated [against] but I never gave up.” In another image, she stands in the middle of a crowded hall. Next to this image, she has written “Education is the key to liberation.”

“It was painful to hear when Carmen shared her experience being bullied, but I was deeply touched when she said ‘I want other transgenders to know they can make it. They can get an education. They can achieve all their goals.’” Pacificar says.

Santos’s profile sends a message about family that is bittersweet to look at, at least for me: Her images are firmly grounded in home and family, and the acceptance she feels from her parents is in every photograph. “When we met her, she also started telling us about her family. And how they were so supportive of her identity as a queer Filipina,” Pacificar says.

The images convey this so well: Many of the photos of Santos include her parents and her sister, from the jumping shot of her family suspended in mid-air, smiling, to a photo of her sitting next to her mother. Next to the photo is written, in Santos’s handwriting: “I wanted to wear shorts and pants, mom wanted dresses. We fought for years. One day I came home and my mom said she bought me two pairs of boxers. Our war ended.”

The love and support in the family was palpable when Pacificar and Tuazon entered Santos’s house for the photo and video shoot. “The first step we took inside their home, you can read that support from wall to wall. Diplomas, awards and medals next to their family photos,” Tuazon says.

These images are powerful and necessary — images of family, survival and support from the queer Filipino/a community are important but often difficult to find. But it’s the story that Santos, Ilano, Hinayon and Ana wish to share that drives the project and its message. “All our participants have … faced struggles [that aren’t] uncommon in our community. But what makes them all great role models is their journey to overcome obstacles,” Pacificar says.

These are the images I needed growing up, and the images that Pacificar and Tuazon needed, too. The Malaya Project takes our search for community, especially as LGBTQA people of color, and presents it to us: The role models we have and maybe wish we had.