Alewives: The Women Who Crafted Beer and Split Hell Wide Open

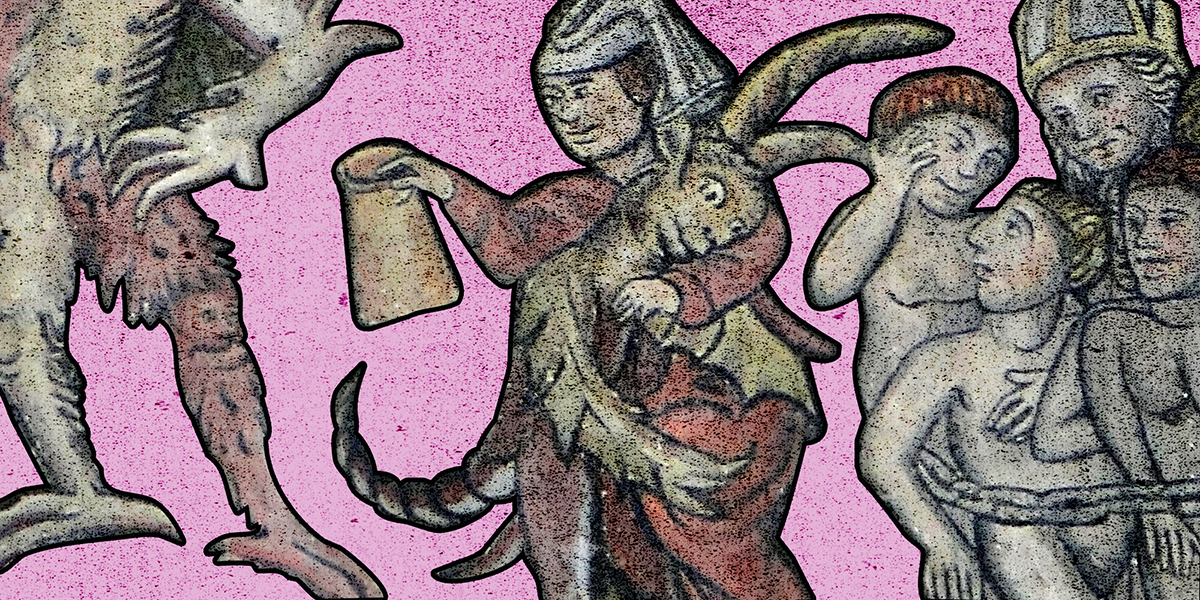

An alewife cradling a demon as seen on England’s largest doom painting at St. Thomas church in Salisbury.

In 1948 the Supreme Court of the United States upheld a Michigan law that prohibited women from obtaining bartender licenses, unless the bars where they worked were owned by their fathers or their husbands. Justice Felix Frankfurter delivered the majority opinion of the court, writing that women bartenders “give rise to moral and social problems.” He pointed to the irrefutable evidence presented by writer of fictional history William Shakespeare, specifically his portrayal of the “sprightly and ribald” alewives who had caused “wantonness, brawls, frays, and other inconveniences” in England’s social life for centuries.

Shakespeare actually only trots out alewives in two of his plays. Once when Henry IV peeps up an alewife’s skirts and once in The Taming of the Shrew when Petruchio’s nemesis, Christopher Sly, breaks a bunch of beer mugs and spends the rest of the play making fat jokes about the alewife who asked him to pay for his mess.

It seems likely that Justice Frankfurter, a renowned anglophile and sexist, misremembered exactly where he’d encountered alewives during his time studying and teaching in England. They do play a very minor role in Shakespeare, but the place where alewives actually reign ubiquitous is hell. Alewives grinning and riding piggyback on the shoulders of demons, sloshing their beer on their descent into the eternal abyss. Alewives pushing wheelbarrows full of innocent men into Satan’s flames with one hand and pounding a pint with the other. Alewives tenderly cradling the horned heads of hoofed hellbeasts to their bosoms while their fellow humans burn alive in chains. The only thing more popular than alewives in religious art depicting hell is the devil himself.

There was a time, however, when alewives were the saints of society. They were celebrated to the point of reverence, and rightly so: For thousands of years they kept their families and communities alive by brewing and serving and selling beer.

In fact, in every ancient society where beer existed, the craft was created and carried out by women. Often, they even received their instruction from goddesses they conjugated with for life. There’s no mythology in which a male god gifts brewing instructions to humanity, and no mythology in which a man receives brewing instructions from a deity. It’s always goddesses and it’s always women brewers.

“It is the onrush of Tigris and Euphrates.”

Most historians agree that beer originated in the Sumerian settlement of Godin Tempe, an outpost on the Silk Road trade route, between 3500-3100 BCE, where it became a staple of daily diets because it contained loads of nutrients from the grains used to brew it. The other thing historians agree on is that the process of brewing in Godin Tempe was initiated and cultivated by women.

Ninkasi was the goddess who gifted women with instructions on beer brewing; in fact, the oldest known writing about beer is The Hymn to Ninkasi (written down around 1800 BCE), which reads half like an ale celebration and half like erotic poetry. Here’s Ninkasi working her ministrations, soaking her malt in the jar, the waves rising and falling and rising and falling. Here’s Ninkasi holding on with both hands to the honey and the sweet wort, the waves rising and falling and rising and falling. Here’s Ninkasi at the climax, pouring the beer out of the vat, the life-giving onrush of Tigris and Euphrates!

Ninkasi was the brewer of beer, but she was also the beer itself. Her spirit and essence infused the beer her priestesses prepared. Her name literally means “the lady who fills the mouth.”

Sumerian women created dozens of styles of beers, mixing them with spices, tree bark, peppers, crab claws, and many herbs that were also found in ancient medical remedies. That’s no surprise: Ninkasi was also associated with healing because she was born when the Mother Goddess Ninhursag was giving life-saving care to another god. (Hang on to that; it’s going to become important.)

Ninkasi wasn’t the only goddess who taught the craft of brewing to eager women. In Baltic and Slavic mythology the goddess Raugutiene provided protection over beer. In Finnish mythology Kalevatar brought beer to earth by mixing honey with bear saliva. For the Pharaonic Egyptians, the goddess Hathor invented beer. Viking women were the exclusive brewers in Norse society and law dictated that all brewhouse equipment remained always in their possession.

“Then put it again into the Cauldron, and boil it an hour or an hour and a half.”

By the time the middle ages rolled around, women in Europe were brewing beer every day. They were called alewives.

The height of alewife popularity came after The Black Death of 1348, which wiped out between one-third and one-half of Europe’s population. Post-Black plague socioeconomic effects have been well-documented by historians; for the alewife, the change came in the form of not having families to prepare beer for, and in families not having an alewife to prepare beer for them. Because the boiled — therefore bacteria-free — water that went into beer made it the only drink that didn’t kill people, selling and buying it became a necessity that proved lucrative for women who’d learned the craft.

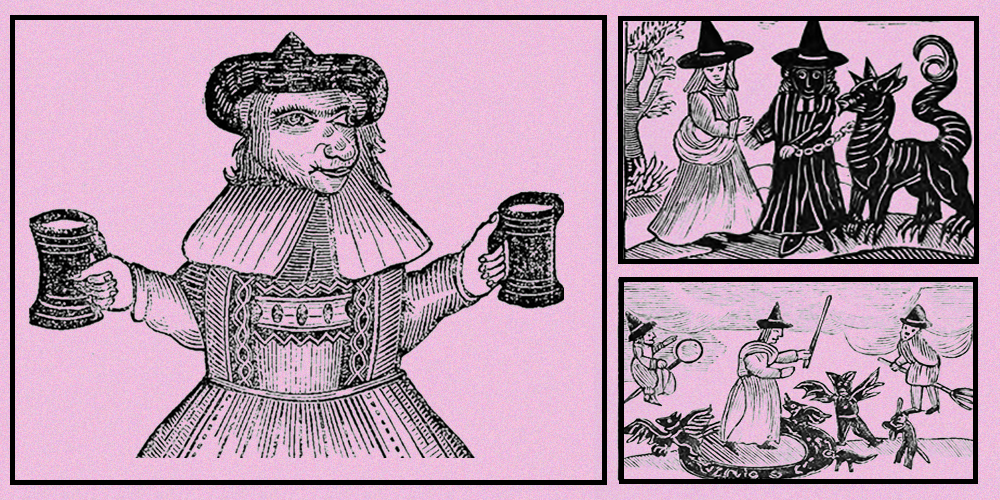

Here’s what an alewife looked like: She did her brewing in a giant cauldron; boiling water, adding grain, overseeing the fermentation process. To keep the mice away from her stores of grain, she kept plenty of cats around. When she had extra beer to sell, she put a broom out in front of her house to signal the surplus. Or, she went to the market, where she took the fashion of the day — the henin, a tall white steeple-shaped hat — and made it black, to stand out in the crowd.

“She is ugly fayre; Her nose somdele hoked; And camously croked.”

By the 1500s, the church had had it with alewives. They were usurping the structures the church had been using to strip women of their agency and autonomy for over a thousand years. Land ownership? Nah, alewives just needed a cauldron. Husbands? Nah, alewvives didn’t need any land. Alewives were perfectly capable of making money without men. They were, quite literally, destroying the patriarchy with their beer.

The only thing medieval Europeans liked more than a good, warm ale was a good, warm story about hell. Dante’s Inferno had captured the minds of a continent ravaged by a plague, and the church leaned into the obsession and started centering almost all of their teachings on Satan and eternal damnation. To accompany these sermons, churches began commissioning art inspired by Dante’s conception of hell. Doom paintings became the chapel fashion of the day, sprawling murals on walls and ceilings depicting Christ’s Last Judgment and the poor disobedient souls he was forced to condemn to hell.

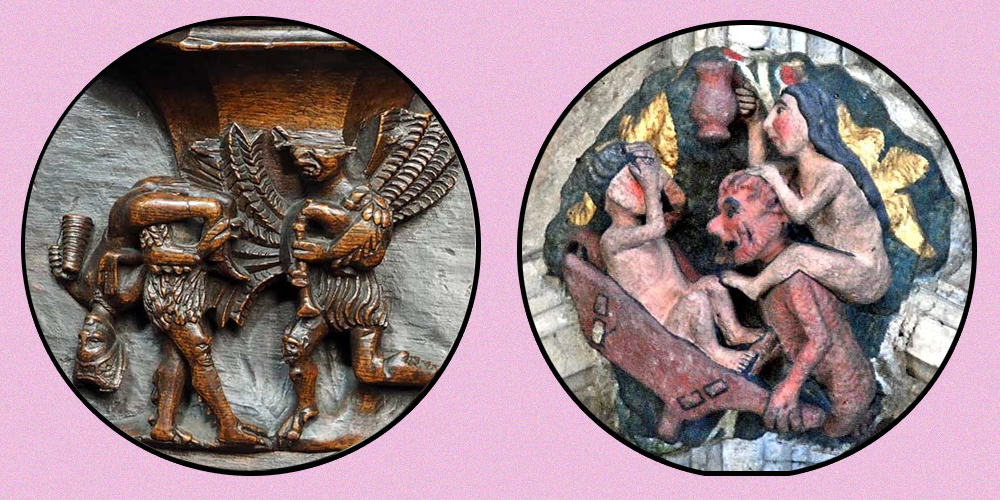

Left: An alewife being thrown over a demon’s shoulder and taken to hell on the most famous Misericord of St Laurence. Right: An alewife riding piggy-back on a demon as they cart a human off to hell, as depicted on the ceiling of Norwich Cathedral.

Priests helped shaped the direction of these paintings and sculptures, of course, and urged the artists to include alewives in their work. By the time Michelangelo finished his doom painting in the Sistine Chapel, alewives were depicted in hell more than any other profession in Europe (and they remain so to this day).

Along with the paintings came the poetry and the plays. The most famous was John Skelton’s The Tunning of Elynour Rummyng, a long, raucous, bawdy poem about an alewife named Elynour who ran a public house (pub). The poem describes her beer as “pig piss,” made while chickens roost over the fermentation tank, while Elynour herself seduces her male patrons, cheats them, lures them into gambling away their family’s money, steals their possessions and steals them from their wives. She looks like the real-life alewife everyone was familiar with, but: with a hooked nose, warts on her face, long spindly fingers, a crooked back.

For all its bawdiness, The Tunning of Elynour Rummyng so closely resembles a liturgical chant — in form and theme — that historians have sometimes wondered if it was, in fact, written by a priest.

Slowly but surely, thanks to the church’s propaganda, Europeans came to see alewives not as legitimate business owners doing a service for their community but as immoral, filthy, ugly, duplicitous women in league with the devil himself. The most popular morality plays of the day, The Chester Plays, dedicated one entire day to the alewife. In Play 17, The Harrowing of Hell, she descends into satan’s realm and happily recounts her debaucherous life to her demonic best friends.

In 1540 the city of Chester banned women between the ages of 14 and 40 from brewing or serving beer, a case recounted 300 years later, an ocean away, by Justice Frankfurter.

“Ye monsters of the bubbling deep, Your Maker’s praises spout.”

By the time witch hysteria set in in the 1600s, the church had learned a few lessons.

They’d reversed the policy of denying the existence of witches. Before the Black Death, the church painted witches as mythological women associated with pagan traditions, or as fictional figures associated with healing and teaching. After the Black Death, the church actively began presenting witches as slaves of the devil. With a continent’s psyche ravaged by a population-decimating plague and everyone looking for divine reassurance that it wouldn’t happen again, a demonic scapegoat became just the thing.

Church interrogators tracked down, tried, and executed “plague-spreaders,” most of whom were women who’d been in charge of healing in their towns and villages before the Black Death.

Left: Portrait of Elynour Rumming, as depicted in the fourth printing of Skelton’s poem. Right: Witches, as depicted on mass-produced witch-hunting pamphlets in the 1600s.

The witch trials used a blueprint that was already in place. Harvests were failing, wars were spreading, someone must be blamed for God’s wrath. The church had spent a century creating visual and narrative propaganda to depict the tall-hatted, cauldron-carrying alewife as a woman in league with satan. It wasn’t much of a stretch to extend that depiction to include women who had extensive knowledge of medicinal herbs and plants and spices.

From the beginning of time, the goddesses associated with beer were also the goddesses associated with birth and healing.

After the witch trials, both medicine and beer brewing existed completely under the dominion of men.

“I’m delighted to see the Supreme Court is interested in beer drinkers.”

Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter made one grave mistake. In 1960, Harvard Law Professor Albert Sachs suggested that Frankfurter take on Sachs’ star student as a clerk. Frankfurter agreed the student had an impressive resume, but he refused to hire her because she was a woman. 33 years later Ruth Bader Ginsburg shared that story when she was appointed to the Supreme Court, telling her own clerks that Frankfurter’s refusal to hire her based on her gender was the reason she became interested in the role of women in the eyes of the law.

Her first major Supreme Court victory came in 1976, when she was working for the ACLU. She offered to file an amicus curiae brief on behalf of a plaintiff who was arguing — like the Michigan bartender in 1948 — that gender was covered under the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. SCOTUS sided with Ginsburg and ruled in favor of the plaintiff.

When Ginsburg began her litigation career, SCOTUS had never encountered a gender discrimination case it didn’t consider reasonable and constitutionally sound. After Craig v. Boren, she went on to win so many gender equality cases using the ruling that the Fourteenth Amendment became affectionately known as the “Ruth Bader Ginsburg Equal Protection Clause.”

Craig v. Boren was a double blow to Frankfurter’s legacy. The case was about the difference in legal drinking ages of men and women in Oklahoma. The plaintiff just wanted to buy a beer.

“It is warm and dry, and has a moderate moisture, and is not very useful in benefiting man.”

The history of beer is rampant with men violently wrenching the art of brewing from the women who created, perfected, and sustained it — but, like all women-centric history, it’s also replete with tales of women who kept their craft’s secrets out of the hands of men. Queer nun Hildegard of Bingen, nursing a broken heart from the death of her lover who was sent away from Hildegard’s abbey when her brother uncovered their relationship, discovered the benefits of hops in beer, both as a preservation agent and a taste modifier. In her journal extolling the virtues of hops, however, she noted they wouldn’t be useful to men. “It makes the soul of man sad,” she wrote. In oral and written fairy tales, passed down from grandmothers to mothers to daughters in perpetuity, facts about medicinal herbs and spices and tinctures are tucked away between stories of morality and romance. The Hymn to Ninkasi is, in fact, the oldest written ale recipe. Woven between the hypnotic queer eroticism are detailed instructions for brewing beer; a sacred, feminine, life-sustaining craft. ![]()