Adrienne Rich was born in Baltimore in 1929. Rich’s father was a pathologist who cultivated his daughter’s early affections for literature and her mother was a concert pianist who’d given up her career in favor of marriage and child-rearing.

Adrienne Rich would eventually go on to study at Radcliffe (Harvard’s college for women at the time), where all of her teachers were men and one of them was W.H. Auden. Auden praised the poems in 21-year-old Rich’s first volume of poetry, A Change of World (1951), as “neatly and modestly dressed, speak quietly but do not mumble, respect their elders but are not cowed by them.”

Adrienne Rich remained, as she grew up, neat and modestly dressed. But she ceased speaking quietly, instead becoming one of the most influential poets and thinkers of the 20th century, known for her radical feminist politics, anti-war activism, literary prowess and contributions to lesbian scholarship and discourse. During a time when women’s liberation seemed focused solely on the needs of white middle-class straight women, Rich was uniquely outspoken on the importance of issues facing lesbians and women of color.

All of us — especially all of us here, the queers and the women — are indebted to Adrienne Rich and all the words she wrote and spoke during her 82 years on earth. Yesterday, March 27, 2012, was the last day of those 82 years.

She died + a famous woman+ denying

her wounds

denying

her wounds + came + from the same source as her power

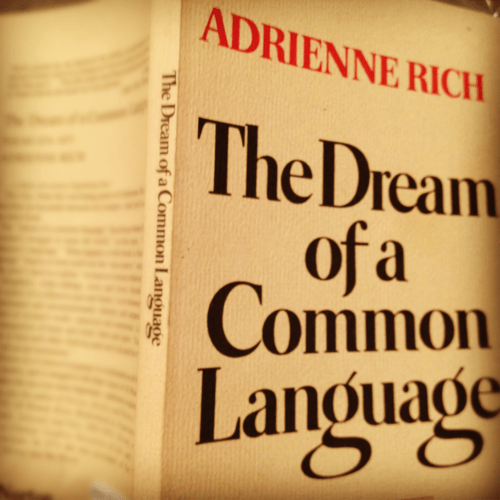

– from “Power” (The Dream of a Common Language)

In The New York Times Book Review, Carol Muske wrote of Rich that she began as a “polite copyist of Yeats and Auden, wife and mother. She has progressed in life (and in her poems …) from young widow and disenchanted formalist, to spiritual and rhetorical convalescent, to feminist leader…and doyenne of a newly-defined female literature.

**

“The connections between and among women are the most feared, the most problematic, and the most potentially transforming force on the planet.”

**

Before sitting down to write this, I decided to do a quick scan of my personal library to see what Adrienne Rich writings I had on hand to pull from and I realized that I didn’t know where to start looking. See, Adrienne Rich is just so awesomely and uniquely prolific. My books are arranged by genre and Rich could be anywhere on those shelves — Poetry, Feminism, Queer Theory, About Writing, Essay Anthologies. She just did so many things. I’ve read Adrienne Rich’s work in at least three entirely unrelated college courses and like Rich, I’m a Jewish feminist lesbian writer who cares about literature and also about social justice. So she comes up a lot.

The first thing I found was a copy of The Dream of a Common Language (Poems 1974-1977). My friend Meg gave it to me twelve or so years ago, when I was living in Michigan and she was still living in New York. My copy is an early printing (1978, I think), bound and covered in tan cardstock with the title and other relevant information printed in large, understated red and black letters.

Meg stuck a post-it note on page 23 for me, and it’s still there:

“I thought you might like these ’21 Love Poems.’ I like some of these other ones too. I hope you do. Hope you don’t mind used edition, but obviously cheaper. There’s a good used bookstore on 12th street right next to where I work…. dangerous. xo meg”

I did like the 21 love poems and many of the other ones, too.

Rain on the West Side Highway,

red light at Riverside:

the more I live the more I think

two people together is a miracle.

– from Love Poem XVIII (The Dream of a Common Language)

Then mostly I just found things here and there — like her 1984 essay “Notes Toward a Politics of Location,” included in The Essential Feminist Reader. The intro describes the essay like so: “In this essay, Rich acknowledged her own ‘politics of location’ as a North American, white, jewish lesbian, and she criticized ‘the faceless raceless classless category of all women as a creation of white, western, self-centered women.”

**

Adrienne Rich got married in 1953 to a Harvard economics professor named Alfred, and consequentially birthed three sons. Rich was gifted grant after grant after award after grant after Guggenheim Fellowship. She published her second volume of poetry, The Diamond Cutters, in 1955, but she hates that book now.

She felt weird about her life back then, like how she’d gotten married and had babies and yet lacked all the accompanying feelings society had promised her went along with marriage and babies.

**

“My children cause me the most exquisite suffering. It is the suffering of ambivalence: the murderous alternation between bitter resentment and raw-edged nerves, and blissful gratification and tenderness. Sometimes I seem to myself, in my feelings toward these tiny guiltless beings, a monster of selfishness and intolerance.”

– Adrienne Rich’s journal, 1960

**

In 1966, the family moved to New York City. By this point Rich was becoming increasingly politically and socially conscious, both as a woman and simply as a citizen, and while teaching at Columbia University she got heavily entrenched in the New Left activity happening at the time. In addition to publishing in feminist journals, she participated in various political actions and threw fundraising parties for The Black Panthers and anti-Vietnam protestors. Her husband was okay with her political passion at first and then less okay with it. He told his friends that Adrienne was losing her mind and was “becoming a very pronounced, very militant feminist.” They divorced. Shortly thereafter, Alfred drove into the woods with a gun and committed suicide. Rich and her children were devastated.

**

“in the nineteenth year and the eleventh month

speak your tattered Kaddish for all suicides:

Praise to life though it crumbled in like a tunnel

on ones we knew and loved

Praise to life though its windows blew shut

on the breathing-room of ones we knew and loved

Praise to life though ones we knew and loved

loved it badly, too well, and not enough

Praise to life though it tightened like a knot

on the hearts of ones we thought we knew loved us

Praise to life giving room and reason

to ones we knew and loved who felt unpraisable.

Praise to them, how they loved it, when they could.”

― “Tattered Kaddish”

**

The Guardian in 2002 wrote of what happened next: “For many, the revelation that [Rich] was a lesbian came as a shock. Observant readers of Rich’s work, however, would have noted that, as early as A Change of World , a poem called “Stepping Backward” had dealt with breaking off a close female relationship.”

She kept on publishing: Necessities of Life in 1966, Leaflets in 1969. 1973’s Diving into the Wreck, which won the National Book Award in 1974, is perhaps her most celebrated volume of poetry.

**

The only real love I have ever felt

was for children and other women

everything else was lust, pity,

self-hatred, pity, lust

– from “The Phenomenology of Anger” (Diving into the Wreck)

**

Rich and Allen Ginsberg shared the National Book Award that year, but Rich refused to accept her award individually, and instead brought up fellow nominees Alice Walker and Audre Lorde with her to accept “on behalf of all women.”

In 1976, Rich met Michelle Cliff, a Jamaican-born novelist and editor who would remain Rich’s partner for life. Rich by then was churning out some world-changing shit, like Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence, a pioneering work that focused on “how and why women’s choice of women as passionate comrades, life partners, co-workers, lovers, community, has been crushed, invalidated, forced into hiding.”

**

“[Responsibility to yourself] means resisting the forces in society which say that women should be nice, play safe, have low professional expectations, drown in love and forget about work, live through others, and stay in the places assigned to us. It means that we insist on a life of meaningful work, insist that work be as meaningful as love and friendship in our lives.”

-Adrienne Rich, “Claiming an Education“

**

She published the controversial and widely influential Of Women Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution in 1976. There, she described her lesbianism as both political and personal, writing of her sexual evolution: “the suppressed lesbian I had been carrying in me since adolescence began to stretch her limbs.”

She wrote more books of poetry, like Twenty-One Love Poems, which was more like a “pamphlet” and ultimately was folded into the book I have, The Dream of a Common Language. In 1979 she published On Lies, Secrets and Silence: Selected Prose, 1966-1978.

**

Men have been expected to tell the truth about facts, not about feelings. They have not been expected to talk about feelings at all.

Yet even about facts they have continually lied.

We assume that politicians are without honor. We read their statements trying to crack the code. The scandals of their politics: not that men in high places lie, only that they do so with such indifference, so endlessly, still expecting to be believed. We are accustomed to the contempt inherent in the political lie…

Lying is done with words, and also with silence.

– “Women and Honor: Some Notes on Lying”

**

I had that book — On Lies, Secrets and Silence — but I can’t find it today. I must have lent it to somebody. I remember transcribing big chunks of it for the straight girl I was sleeping with, using Rich’s words to make some kind of passive-aggressive point. I wish I still had it.

**

Cliff and Rich eventually relocated to Santa Cruz, where the couple took over the editorship of lesbian journal Sinister Wisdom. Then more teaching, and more writing: six years at Cornell, three volumes of poetry, more prizes, more grants.

She started Bridges: A Journal for Jewish Feminists and Our Friends in 1990 and became active on the advisory boards of the Boston Woman’s Fund, National Writers Union and Sisterhood in Support of Sisters in South Africa.

**

“We [poets] may feel bitterly how little our poems can do in the face of seemingly out-of-control technological power and seemingly limitless corporate greed, yet it has always been true that poetry can break isolation, show us to ourselves when we are outlawed or made invisible, remind us of beauty where no beauty seems possible, remind us of kinship where all is represented as separation.”

**

In 1994 she received the MacArthur “Genius Grant” and in 1997, Rich was awarded The National Medal for the Arts but famously turned it down in protest against the House of Representative’s vote to end the National Endowment for the Arts. She has said of that choice: “I am not against government in general, but I am against a government where so much power is concentrated in so few hands.”

She told President Clinton, in a letter: “The radical disparities of wealth and power in America are widening at a devastating rate. A president cannot meaningfully honor certain token artists while the people at large are so dishonored.”

Rich continued publishing poetry and essays, like 1981’s A Wild Patience Has Taken Me This Far and 2001’s The Fact of a Doorframe. She continued participating in anti-war efforts, and became a chancellor of the board of the Academy of American Poets.

I could write about her all day. I’ve already written 1964 words, this is already too long, and all I’ve done so far is lay out the facts. I’ve not yet gotten into the feelings. She was such a good woman, so uncompromising in her politics, so dedicated to her work. But this is already too long, and I’ve only just gotten started.

**

At twenty, yes: we thought we’d live forever.

At forty-five, I want to know even our limits.

I touch you knowing we weren’t born tomorrow,

and somehow, each of us will help the other live,

and somewhere, each of us must help the other die.

– From “Love Poem III”

**